Law & Politics

Germany Is Known for Its Heavily Funded, Thriving Art Scene. But a Slew of Cancellations Is Threatening That Reputation

Increasingly, cultural workers are discussing boycotting Germany.

Increasingly, cultural workers are discussing boycotting Germany.

Hanno Hauenstein

Oyoun, a cultural center in Berlin, has found itself entangled in a fight for survival over the past few weeks.

A diverse group of local residents oversees the center, which promotes decolonial, queer-feminist, and migrant perspectives. By the end of this year, the space will be without a home; last month, the Berlin senate withdrew its funding from Oyoun, which included the roof over its head.

It appears that the center’s refusal to follow the senate’s request to cancel an event in November, organized by an anti-Zionist left-wing group called Jewish Voice for a Just Peace in the Middle East, to commemorate both victims of Hamas terror and Israeli airstrikes in Gaza, led to the decision. Berlin’s culture senator Joe Chialo announced the funding cuts for the cultural center in a hearing, noting his opposition to “every hidden form of antisemitism;” a more precise rationale behind the cuts was not revealed and a request for clarification was not received by the time of publishing. Louna Sbou, an Oyoun representative, has stated that so far all the team’s efforts to communicate with the Berlin senate have failed.

For a country and capital city known for its robust support of the arts, the ousting of Oyoun shocked many. Both in and outside of Germany, the country invests billions in museums, theaters, culture exchange programs, and artists; in 2020 alone, funding totalled €14.5 billion ($15.5 billion).

But recent cancellations—Oyoun is one of around 40 known projects (within culture and beyond) called off or postponed since October 7—and growing fear that artists may lose funding and opportunities due to political views on Israel-Palestine that differ from the official state narrative—are casting a shadow on the nation’s reputation as a bastion of free expression. At the same time, more and more public figures are circumventing Germany’s invitations and funding, in protest of its current policies.

Interior view of the gallery at Oyoun. Photo: Anna Wyszomierska

On November 13 exhibition titled “We ist Future” (“We Are Future”) at Museum Folkwang, a prominent museum in Essen, was canceled over Instagram posts by the show’s Haitian curator, Anaïs Duplan, in which they described Israel’s retaliation in Gaza as a genocide. A week later, the Biennale für aktuelle Fotografie, a contemporary photo exhibition, set to take place across three German cities next year, was called off when organizers discovered that one of the principal curators had disseminated an interview on social media drawing a parallel between Israel’s actions in Gaza and the Holocaust.

Despite the differences between cases, recent suspensions are driven by a heightened sensitivity over Israel-Palestine, highlighting a climate of fear, avoidance, and distrust. Some people see the dire scenario in the German cultural sector as a paradigmatic case within the larger context of Germany’s tested state cultural funding landscape.

At the same time, instances of anti-Israeli and outright antisemitic incidents in Germany have seen a troubling surge: One particularly alarming event involved the throwing of two Molotov cocktails at a synagogue in the German capital. While these incidents underscore the urgency of concerns, as cancelations continue within the cultural sphere, questions about the protection of free speech, as well as worry over discriminatory patterns that seem to be driving some of them, are becoming ever more pressing.

“The German public funding system is being steadily eroded as the country continues to shift to the right,” said artist Candice Breitz, who has had two invitations canceled by state-sponsored institutions over the last eight weeks. “It seems we are fast slipping back towards the past,” the artist added, “[with] German institutions increasingly prioritising cultural workers who are compliant with mainstream state narratives and don’t ask too many critical questions.”

Event in Berlin “We Still Still Need to Talk” on November 10, co-organized by Candice Breitz. Speakers included author Deborah Feldman and artist and researcher Eyal Weizman. Photo: Hanno Hauenstein

In a press release issued by the the Saarland Cultural Heritage Foundation, a major museum in the state of Saarland that planned to present Breitz’s work, the board stated it would not provide a platform for artists “who do not recognize the terror of Hamas as a breach of civilization or who consciously or unconsciously blur the distinction between legitimate and illegitimate actions.” The Jewish South African artist has been vocal about Israel’s bombardment on social media as well as expressing condemnation for Hamas’s massacre on October 7.

The term zivilisationsbruch (“breach of civilization”), used by the board, appears frequently in German scholarship, almost exclusively as a reference to the Holocaust. Breitz thus felt she was asked to acknowledge an equivalence between the attack by Hamas and the Holocaust as a condition for exhibiting her work

After the Süddeutsche Zeitung framed a comment Berlin-based musician Nicolás Jaar made on Instagram (criticizing a White House statement on the Hamas massacre) as “pro-Hamas,” the paper corrected its comment, but only after Jaar threatened legal action. In an email interview, Jaar called Germany “complicit” with what is happening in Gaza, not only through political means, but also through what he perceived as a deafening silence of several cultural institutions. “The intimidation tactics work, and I’m seeing people self-censor in order to continue being able to show work,” he said.

Breitz pointed to what she perceives as an excessive level of German self-righteousness, but she also links her cancellations, and those of others, to a national German desire to project an image of having overcome homegrown antisemitism, which is far from true. This effort, she argued, involves projecting antisemitism onto perceived “others.” She finds that this has “most egregiously affected Palestinians, Arabs, Muslims, and others who do not identify as white, but now [also] increasingly seems to be directed towards progressive Jews and Jewish Israelis.”

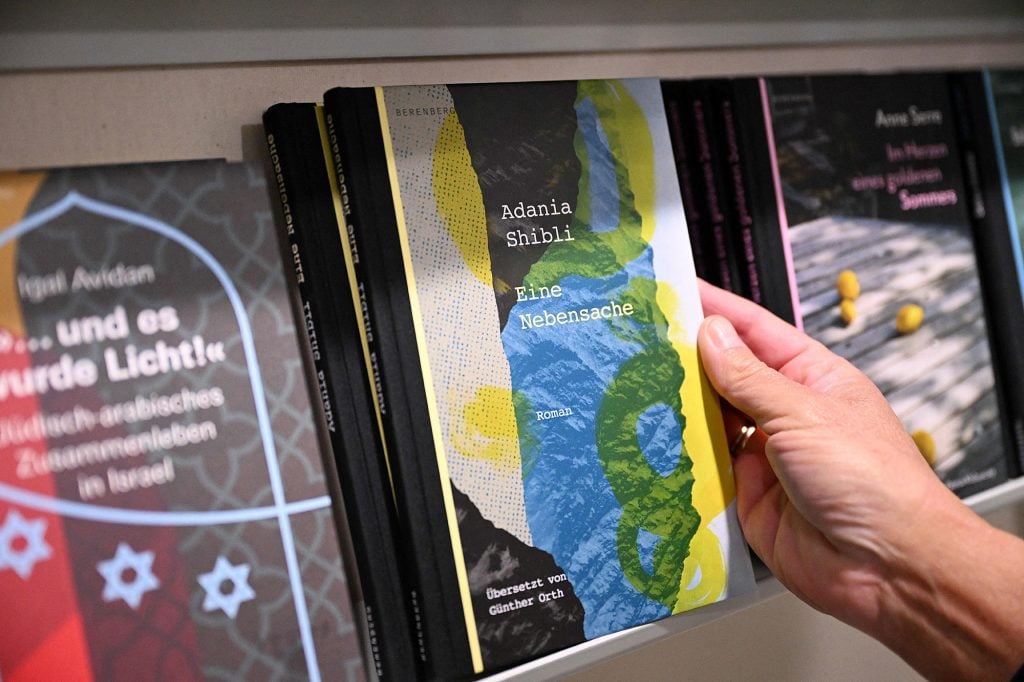

The German edition of the book by Palestinian author Adania Shibli with the title Minor Detail (2017) at the Frankfurt Book Fair in Frankfurt am Main. The Palestinian author’s award ceremony at the fair was postponed due to the Israel-Hamas war. Photo: by Kirill Kudryavstev/AFP via Getty Images

It is important to think about how high the stakes are for artists and institutions in the country. Germany’s cultural framework is extremely reliant on public funds, and its vast network of institutions is opposed to the U.S. model, and much less often subsidized by circles of private patrons. Take the capital of Berlin alone, which has culture funding proposed for 2024 that sums up to nearly €1 billion ($1.1 billion), more than public funding for the entirety of England. At the same time, up until recent years, the impression has been that German politicians keep an arm’s length when it comes to influence over the opinions of the people and centers they pay for.

Despite not yet being officially passed, the government budget for 2024 expects a significantly lower cultural budget than the current one. For the coming year, the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media plans to spend around €254 million ($274 million) less than its 2023 target. In light of a recent motion by the German government for a resolution that addresses antisemitism and Germany’s historical responsibility, some artists and institutional representatives in Germany are concerned about even further narrowing of artistic freedom within a tightening economic situation.

Germany’s cultural sector has increasingly grappled with the boundaries of legitimate critique towards Israel in recent years. The collision highlights Germany’s staatsraison—an abstract pro-Israel policy derived from well-intentioned attempts to atone for the Holocaust by supporting Israel. It often leads to staunch pro-Israel rhetoric taking precedence over a pluralistic discussion and debate.

Visitors of the documenta fifteen stand in front of the Museum Fridericianum. The art exhibition runs until 25.09.2022. The Bundestag debates the scandal with anti-Semitic symbols at the art exhibition documenta. Photo: Swen Pförtner/dpa (Photo by Swen Pförtner/picture alliance via Getty Images)

In particular, the exhibition Documenta has become a flashpoint; the show, which takes place every five years, received €42.2 million ($45 million) of state money for its last edition in 2022. Yet its future is very much an open question following the controversy around Documenta 15, in which German authorities overseeing it struggled to draw a line between artworks and perspectives critical of Israeli government policy on the one hand, and acute, indefensible antisemitism on the other. The issue continues to haunt the institution: last month, Documenta’s entire finding committee for its next edition resigned.

A senior representative from a major cultural institution in Germany, who asked to remain anonymous, said the country’s status as an exceptionally free environment is at risk of disintegrating. They noted a pervasive fear of job loss or loss of funding from within institutions. “Nobody wants to be publicly associated with [the issue of Israel-Palestine], people are afraid to like things on Instagram, some have even stopped writing emails on the subject. Everyone’s afraid of saying or doing the wrong thing,” they said.

Consequently, according to the representative, the vetting process often takes informal forms, especially concerning Muslim artists. “Someone comes and says: ‘This or that person gives me a strange vibe’—and that’s often enough to forego a collaboration,” they said. “It’s truly a form of preemptive, Foucauldian obedience, where everyone has internalized the rules, and everyone watches each other. That’s the direction this is going.”

They emphasized an urgent need to refine the terminology on Israel-Palestine and related issues. However, the representative lamented that the conversation hadn’t progressed to a point where open dialogue was feasible. “That’s why so many people talk about McCarthyism,” they noted.

Certainly, governments should not fund hate speech or antisemitism, but a close look at the situation shows a complicated environment. The clash between Germany’s commitment to pluralism and its staatsraison policy has been most poignantly demonstrated by the Bundestag’s contentious 2019 resolution, which, despite not being legally binding, deems the BDS (Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions) movement to be antisemitic. In the time since, artists, cultural workers, and cultural institutions in Germany have criticized it for creating a climate of immobility and self-censorship, a critique that was voiced explicitly, even by some institutions that reject BDS tactics, including the Goethe-Institute and the Humboldt Forum. The latter institutions joined forces with the so-called Initiative Weltoffenheit, an association of German cultural institutions that have deemed the “logic of boycott,” triggered by the resolution, “dangerous.”

Germany’s apprehension over boycotting Israel stems from history, with many drawing parallels with Nazi-era boycott campaigns effectively seeking to shun Jewish businesses in the 1930s; the legacy of the Holocaust and its central role in post-war German identity amplifies this unease. In light of the very real threat of antisemitism resurging, many Germans rightfully navigate these issues with heightened vigilance. Increasingly, however, Germany seems to effectively leverage its attempts to reckon with its brutal, antisemitic past by pushing back on the right of Palestinians, foreigners, and left-wing Jews to express critical views on Israel-Palestine.

Germany’s culture minister Claudia Roth. Photo: Hannes Albert/dpa via Getty Images

Palestinians in particular often find themselves portrayed as a threat to the Jewish community by German media and policymakers and regarded as somewhat guilty by association, until proven otherwise. And since October 7, the debate over permissible speech within state-funded cultural spheres has become increasingly contentious.

An Israeli artist based in Germany, says that cancellations aren’t the answer. “I strongly reject boycotts”, they said, “especially in culture, and that goes for institutions and artists alike.” Even so, they felt irritated by how polarized this discussion often becomes when discussing the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. “I view myself as a progressive Jew, but I find it problematic to portray progressive Jews as holding only one view,” they said, adding that many of the ongoing discussions in Germany are disingenuous. “I often don’t know how much this polarization helps the people on the ground, Palestinians or Israelis. For example, when people on the left cannot even condemn the October 7 mass rape and severe sexual assault that took place in the Nova festival. It’s not actually really even about condemning, but rather to truly acknowledge and to try to understand what this means for those involved. It’s the same as when people on the right say ‘there are no innocent civilians in Gaza.'” They noted that: “these binary discussions often feel tactical.”

Reflecting a growing sentiment among cultural workers, Breitz said that, in this new climate, shaming and boycotting Germany is seen by many as the only way to impart a lesson. “Germany has gone all-out to prevent people from participating in a non-violent boycott against Israel. Now, many people seem to be saying, ‘Maybe it’s Germany that should be boycotted!’”

Evidence suggests that some of this is already happening, within and beyond the cultural sphere. Jaar, the musician, is also thinking about leaving the country. Sharif Sehnaoui, a Lebanese experimental musician, declared on X, and musician Khyam Allami, respectively announced they would reject invitations and boycott German-funded cultural projects. In November, Indian author Suchitra Vijayan declined a German invitation and declared a boycott of Germany because of “what’s going on in Palestine.” Earlier this month, Nikita Sud, an Oxford University professor, said that she rejected a request from Germany to look over a major funding application because of German institutions’ attitude toward Israeli violence against Palestinians.

Among cultural workers, there is talk of several other cases, not all of which are publicly communicated. A South-Asian artist who was supposed to exhibit at the now-canceled Biennale für aktuelle Fotografie noted a sentiment among international cultural workers within Germany as well, who were growing cautious about being too dependent on the German economy, particularly its cultural funding schemes. The representative of the German cultural institution added that they have had artists cancel projects in recent weeks. “There are artists who see what’s happening in Germany as a form of censorship. And there is a fear that some artists will not want to work with us anymore.”

Tanzim Wahab, Shahidul Alam und Munem Wasif (v. l . n. r.) | Photo: © Lys Y. Seng

Concurrently, a link to a shared document titled “Index of Cultural Institutions & Collectives’ Stance Towards The Current Palestinian Liberation Movement” has circulated on social networks in recent weeks. Though no longer openly accessible, it seems to have been initiated with the aim of monitoring and providing information about cultural institutions’ and collectives’ positions regarding Israel-Palestine. The list is undoubtedly far from impartial, marking institutions that express solidarity with Israel or cancel collaborations with labels such as “censorship,” or “silence.” Major German media outlet Der Spiegel suggested that the list serves as a guide for determining which institutions to avoid and thus aligns with the “logic of the BDS movement to isolate Israel.” The Berlin newspaper Tagesspiegel described it as a “pillory list” and reported that the Berlin police were aware of it.

Meanwhile, Oyoun remains embattled. With the help of a crowdfunding campaign that reached €72,000 ($77,555) within the first five days, the venue, which employs over 30 people, has now entered a legal case against the funding cutoff. Despite grassroots support, the future of this platform for pluralist discourse in Berlin hangs in the balance, and it seems to track with one of Breitz’s noted fears: “We are looking at a future that is likely to be very white, and very German.”