Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, dissecting one subject to put an entire system in view…

Maecenas logo. Image courtesy of Maecenas.

EXECUTION STYLE

On Wednesday, art investment startup Maecenas opened online registration to participate in an event it is billing as “the world’s first ever blockchain-based auction of fine art.” But in my opinion, slicing into the details lays bare a number of deficiencies that also apply to much of the overheated art and blockchain space. (If you’re not familiar with that space yet, check out my primer from earlier this year.)

Presented in partnership with Dadiani Syndicate, which brands itself as the first British gallery to accept cryptocurrency payments, the Maecenas auction in question will feature only one work: Andy Warhol’s 14 Small Electric Chairs (1980). The painting will be divided into fractional shares collectively amounting to as much as a 49 percent ownership stake. These minority shares will be distributed to winning bidders paying in Bitcoin, Ether, or Maecenas’s own cryptocurrency, the ART token. Sale and subsequent Wall Street-style trading of these shares will be tracked on a blockchain, allegedly creating what Maecenas calls a “transparent marketplace.”

To Maecenas and Dadiani’s credit, would-be bidders can only participate in the auction after submitting some basic “Know Your Client” and “Anti-Money Laundering” details, including proof of identity and current residence. In theory, this requirement at least prevents the auction from being converted into a washing machine for dirty cash—a legitimate possibility that dogs many crypto-ventures seeking an air of legitimacy and wider adoption.

But what about Maecenas’s stated mission to “democratize access to fine art” via the Warhol auction and others like it? Does the blockchain element deliver the revolutionary promises central to the startup? And what do the answers tell us about the many other art/blockchain ventures swarming the industry like fruit flies to a poorly maintained winery?

Infographic on registration for Maecenas’s first-ever blockchain-based art auction. Image courtesy of Maecenas.

THE PROPOSITION

In its white paper, Maecenas identifies the “fundamental issues of art investment” as “lack of transparency, lack of liquidity, and most importantly the fact that trust is centralized” with traditional entities like auction houses and galleries. (For the uninitiated, the masterminds behind every crypto-venture, including Bitcoin, write a white paper to detail their product, their goal, and how the former achieves the latter.)

By this logic, Maecenas magic-wands the industry by dividing artworks like 14 Small Electric Chairs into tradeable shares, then facilitating and tracking their movements via blockchain technology.

It’s an appealing idea if you want to invest in art but can’t afford a collection, right? Allow more people to buy in by lowering the cost of entry, and place the responsibility for monitoring the marketplace into the hands of infallible, incorruptible software rather than fallible, corruptible human experts.

However, in my opinion, this pitch represents a dramatic misunderstanding of blockchain—one that helps propagate myths about the technology that are driving the gold rush of misguided crypto-art startups.

REALITY CHECK

When people like me try to define the concept of a blockchain to the uninitiated, we almost inevitably fall back on some variant of the phrase “decentralized digital ledger.” Once you explain that “decentralized” means “jointly maintained by different computers in different locations with different owners,” this definition usually helps.

Why? Because a ledger, or an ongoing list of transactions, is a pretty relatable idea. People might picture an Excel spreadsheet tracking expenses or an itemized receipt from a grocery store. Simple, right?

The problem is that these images are somewhat misleading. It’s true that a well-written blockchain tracks all the details of whatever transactional history it’s recording. But it’s false that the info is easy to read if you’re just a skeptical customer without some hardcore software literacy.

A crucial point often lost in the analysis of many blockchain art ventures, and many blockchain ventures, period, is this: There is nothing inherently transparent about blockchains. Not all of their data is publicly viewable by default. The creator has some power to choose what to make visible, and who to make it visible to.

Although I didn’t find the mechanism detailed in Maecenas’s white paper, let’s just assume that their blockchains will all provide maximum data visibility to investors. Otherwise, all the company’s rhetoric about “democratizing access” and using an “open blockchain platform” would be nothing but chemtrails.

The larger, more important issue is that even an accessible blockchain is hard to review. It’s not as if every one of them automatically generates a link to an easily readable table of transactions like the old school examples I mentioned above. The only way to check for accuracy is to do an independent audit of the blockchain at the level of code.

To give you a sense of what that task requires, take a look at the below excerpt from crypto-skeptic Kai Stinchcombe’s essential essay “Blockchain Technology Is Not Only Crappy Technology But a Bad Vision of the Future.” Here, he’s talking about the alleged revolutionary potential of using blockchains to create truly free and fair elections in developing countries.

“Keep your voting records in a tamper-proof repository not owned by anyone” sounds right — yet is your Afghan villager going to download the blockchain from a broadcast node and decrypt the Merkle root from his Linux command line to independently verify that his vote has been counted?

If your response to the above was “WTF does any of that mean?” that’s the point! Even a sharp citizen will be almost powerless on their own in this realm without a pretty rigorous coding background. Unless we’re all intent on turning ourselves into characters from Mr. Robot, this is kind of a problem.

So what is the average person likely to do in a blockchain ecosystem instead? As Stinchcombe writes, probably something like “rely on the mobile app of a trusted third party — like the nonprofit or open-source consortium administering the election or providing the software.”

In other words, any non-hacker buying into blockchain is just choosing to trust software rather than a person or traditional institution. But since software doesn’t magically write itself, “trusting in the software” on some level means “trusting in the people writing the software.” And unless you subscribe to some fringe Silicon Valley cosmology in which programmers are numbered among the saints, there is no reason to believe that people writing software are inherently more trustworthy than people working at auction houses or galleries. And that matters whether you’re investing in fractional shares or hoping for bulletproof provenance verification.

THE TRUST PROBLEM

This leads us back to Maecenas’s Warhol offer. In order to feel good about bidding in a crypto-denominated, smart-contract-activated, blockchain-tracked auction, you first have to trust that:

- The artwork is authentic.

- The owner is the true owner.

- There are no other liens or ownership stakes against it behind the scenes.

- The software has been written fairly and securely (again, unless you’re willing and able to audit it yourself), and…

- The certificate verifying your fractional shares in the painting is enforceable off the blockchain (meaning IRL).

About that last part: Maecenas’s legal and compliance regime is not outlined in its white paper, either. Instead, you get a grand total of six sentences and one confusing diagram on page 10 that I would argue collectively amount to “just trust us, OK?”

In fact, despite the overtures made to “decentralized networks of trust” and the exclusionary inefficiencies of the traditional art industry, reliance on established art-world and business-world institutions runs rampant through Maecenas’s pitch.

Their home page states that “Artworks remain in custody of trusted institutions, vetted collectors, and galleries.” (The particulars of this vetting process are not detailed.) Similarly, both nearby and within the diagram I just mentioned, you’ll find references to Maecenas’s involvement with “art finance experts, law firms, and investment professionals,” as well as unidentified “art experts” who verify every artwork’s authenticity.

And as the diagram makes clear, guess who’s standing at the (ahem) center of all these different traditional experts? Maecenas! Kind of odd for a business using decentralization as a pillar of its mission, no?

This points us toward something that needs to be said more broadly about blockchain ventures and their promises of decentralized disruption of the art market.

Mockup of the Maecenas trading platform. Image courtesy of Maecenas.

THE “PLATFORM” PROBLEM

Maecenas defines itself as a “platform,” a word as pervasive in art/blockchain pitches as sad animals in budget petting zoos. Why is this a practical problem rather than a verbal annoyance? Because “platform” is a synonym for “middleman,” and middlemen are inherently contradictory to any sincere effort to decentralize anything—at least, if they’re charging a fee for their presence at the crossroads.

Maecenas is a perfect example of this. Their white paper states that they charge the consignor of any artwork a six percent listing fee and successful bidders on fractional shares a two percent transaction fee. (Fractional owners are allowed to sell their shares commission-free.)

Unless you’ve recently been slammed in the head with a frying pan, I can’t really give you a pass for preaching the virtues of decentralization while simultaneously pitching yourself as a “platform” for transactions that takes a 2 percent to 6 percent cut. It’s internally inconsistent. It’s like saying, “I love nature, but I’m not wild about plants.”

This brings us to another sirens-blaring, red-alert point about the big picture: Blockchain is a decentralized technology that can still be put toward centralized uses. It’s no different than the argument you’ll hear made about wedding rings by men living in the cesspool that is the pick-up artist “community”: Wearing one can be just as useful for attracting extramarital action as for signaling that you’re off limits.

In tech itself, there is no better example of this reality than the web itself. A technology developed to facilitate the free and fair exchange of knowledge without exposure to filters, discrimination, or tracking has today been transformed by various “platforms” into the most aggressive and extensive advertising, monetization, and mass surveillance apparatus in human history.

Say it with me: Technology is agnostic. Its effects depend on the people using it.

Which begs the question: What do the people behind Maecenas and the Warhol auction actually want?

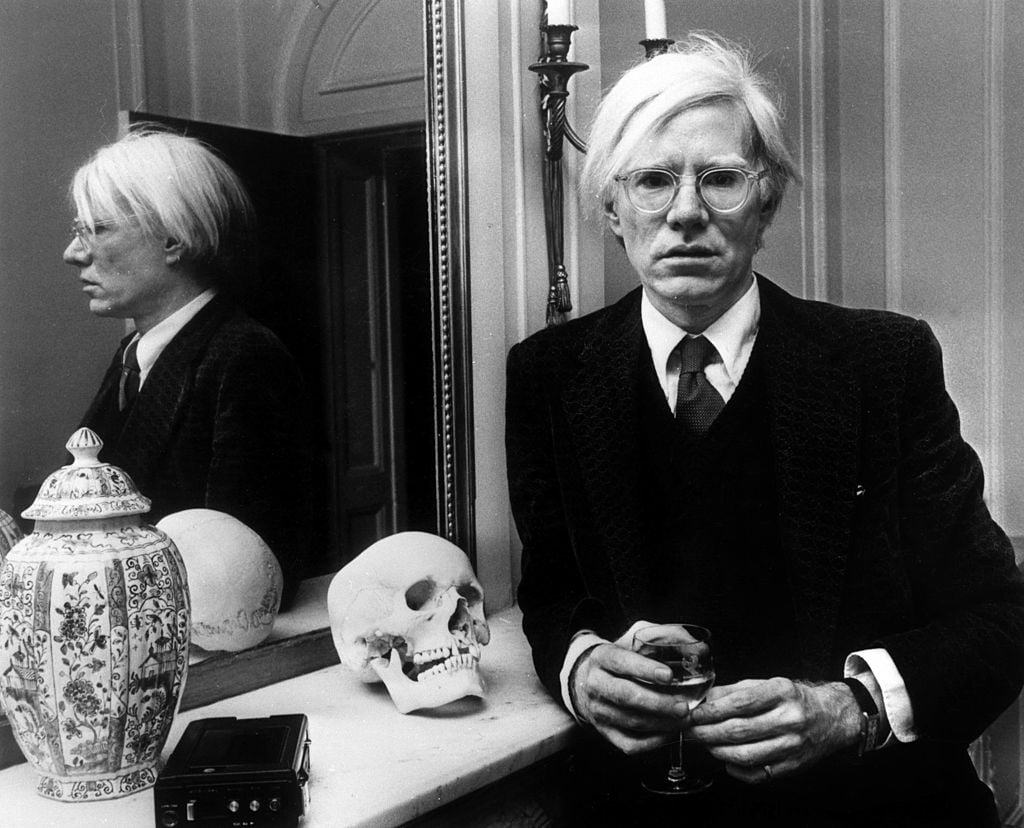

The American artist and filmmaker Andy Warhol with his paintings(1928 – 1987), December 15, 1980. (Photo by Susan Greenwood / Liaison Agency)

WILL THE REAL MAECENAS PLEASE STAND UP?

Maecenas’s press releases and white paper alternate between two stated goals. One is to democratize access to fine art. The other is to democratize access to fine-art investment. Yet these are wildly different objectives, and the “platform” looks much more tailored to one than the other.

This is apparent even in Maecenas’s name. Early in the white paper, they explain their choice of moniker as follows:

We are named after—and inspired by—an early patron of the arts. Gaius Maecenas helped democratize art in Ancient Rome by financing poor poets. We want to be the modern version of Maecenas… ensuring that fine art is available to everyone and not just the ultra-wealthy.

So how does this gel with auctioning off fractional shares in a select group of artworks that, according to the white paper, “will be kept in purpose-built safe art storage facilities” at freeports?

The answer is that “Maecenas, in its effort to democratize access to fine art, will allow investors and their nominated guests to arrange visits to appreciate the artworks” if they’re ready to travel somewhere like Singapore, Luxembourg, Geneva, or New York.

Invoking Maecenas, the Roman arts benefactor, would make sense if Maecenas, the “platform,” was actually, say, a crowdfunding venture that funneled money to working artists experiencing extreme financial hardship. Or, alternatively, if the historical Maecenas’s arts “patronage” had consisted of building a private library of poems where the rights to individual lines or stanzas could be traded in the square, but only read by investors also willing to make an in-person journey to the archive.

But neither of those is true, so the name is ridiculous. To me, it misses the point almost as badly as if someone built a “platform” to invest in the worldwide expansion of British commerce and called it Gandhi.

SUMMING UP

I have a lot of other, smaller questions about both the Warhol auction and Maecenas more broadly. But the key point is that I don’t see how blockchain technology actually solves the issues they want it to. For instance, other startups elsewhere in the world have managed to market fractional shares without blockchains. And if the goal is to make art investing more like investing in the traditional financial markets, well, it’s not as if the likes of E-Trade, Schwab, or Robinhood needed decentralized technology to thrive.

Instead, Maecenas looks to me like a standard-bearer for so many of the art/blockchain ventures bombarding the industry: a monetization strategy with little genuine interest in art or artists, and no real solutions to the problems it’s pursuing. I don’t think they’re evil, just misguided. But if we want this technology to make any significant changes in a troubled ecosystem, we have to keep asking hard questions about its true limitations and potential.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, say what you mean, and mean what you say.