Art History

The Enduring Love Stories of the Harlem Renaissance

Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight were art school sweethearts.

One hundred years ago, in the early decades of the 20th century, a blisteringly brilliant artistic hub coalesced in Harlem, a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, made up of Black writers, poets, painters, musicians, thinkers, philosophers, and seemingly every other type of creative mind. This community, which would give rise to the Harlem Renaissance, emerged as hundreds of thousands of Black Americans moved from the South to cities in the industrial North, in an exodus known as the Great Migration. Offering greater freedoms and opportunities, New York City, and Harlem, in particular, became a mecca for Black Americans and turned the neighborhood into an internationally celebrated bastion for Black culture. During these years, the likes of Langston Hughes, Augusta Savage, Louis Armstrong, Zora Neale Hurston, Aaron Douglas, and W.E.B. Du Bois, were to emerge from this creative community.

Augusta Savage with two of her sculptures. Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Amid this milieu, romance inevitably blossomed, too. The great American sculptor and teacher, Augusta Savage found love, for instance, with the influential African-American newspaper editor and journalist Robert Lincoln Poston. Romance would be found in her classroom as well (read on).

This week, the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” (on view through July 28) an exhibition that offers new perspectives on this era of artistic outpouring. We’re always suckers for a good romance, so we’ve decided to take a closer look at a few of the love stories that the Harlem Renaissance shaped and inspired.

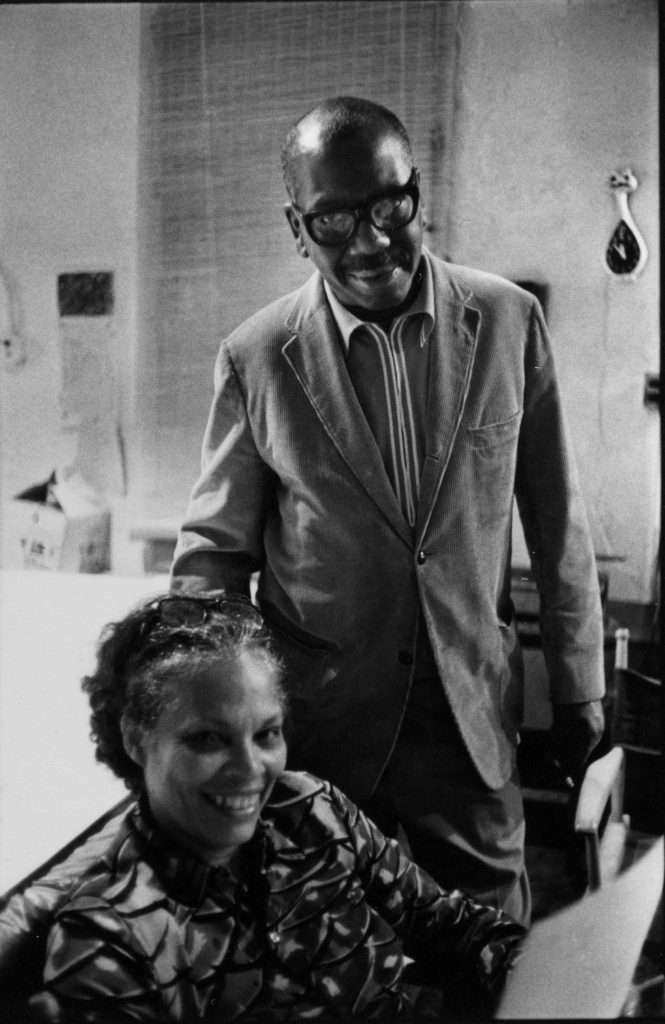

Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight

Portrait of married American artists Gwendolyn Knight and Jacob Lawrence, New York, 1970s. Photo by Anthony Barboza/Getty Images.

An Amorous Education: Gwendolyn Knight and Jacob Lawrence met while students at the esteemed Harlem Community Art Center. There both Knight and Lawrence were taught by Augusta Savage, a famed American sculptor, who helped cement both of the artists’ focus on civic-mindedness. Other leading and early figures of the Harlem Renaissance such as painters Charles Alston and Henry Bannarn proved pivotal forces in their educations.

An Enduring Love, Built Around Community: Knight and Lawrence, who wed in 1941, remained together until Lawrence’s passing in 2000, and shared a common vision for fostering community. These artists’ backgrounds were not without personal struggles, however, Lawrence, who was born in Atlantic City, moved frequently throughout childhood and spent time in foster care. He also struggled with bouts of depression, and after a time serving in the military, Lawrence enrolled in an inpatient mental treatment. Knight, who was born in Barbados, emigrated to the U.S. with close family friends and spent some of her childhood in Missouri, before eventually making her way to New York. Both artists found purpose and inspiration in Harlem, particularly as members of the Works Progress Administration. Lawrence developed a style he called “dynamic cubism” inspired by the sights and sounds of the uptown neighborhood, writing of Harlem: “All these people on the street, various colors, so much pattern, so much movement, so much color, so much vitality, so much energy.”

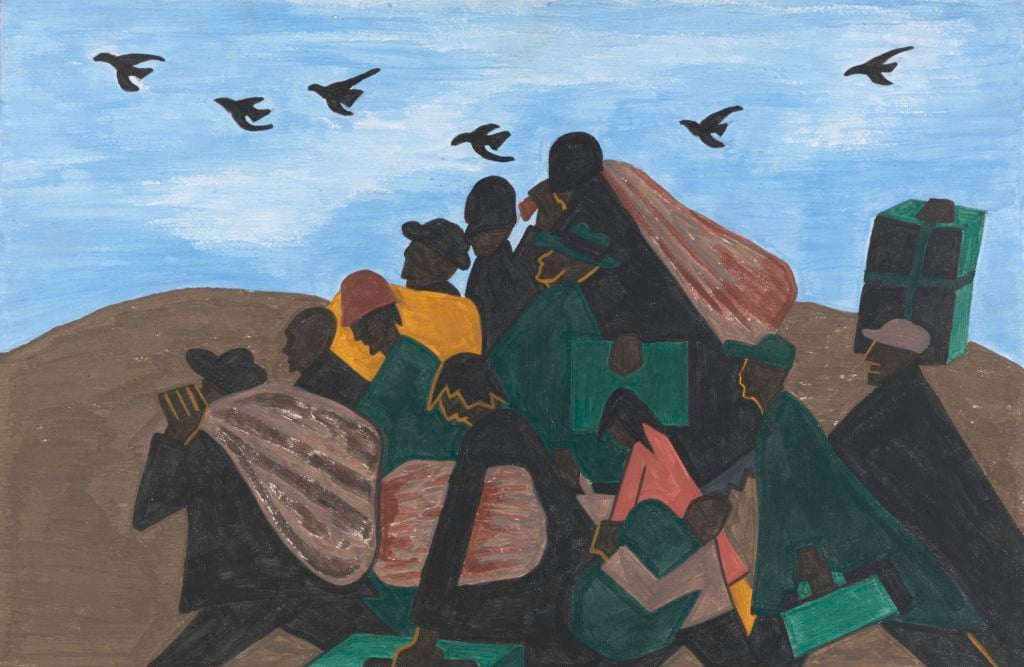

Jacob Lawrence, Panel 3 from The Migration Series, From

every Southern town migrants left by the hundreds to travel

north (1940–41). © 2019 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In New York, Lawrence created his career-defining 1941 “Migration Series,” which focused on the Black American migration from the rural South to industrial cities of the North—the series would be exhibited at Edith Halpert’s pioneering Downtown Gallery in Greenwich Village (he would become the first African American with official gallery representation with the show). Knight assisted Lawrence with the series, preparing gessos and captioning multi-panel works. Outside of her artistic endeavors, Knight was a tireless philanthropist who devoted herself to children’s causes, particularly. In 1999, the couple established the Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation, which fosters the study and creation of American art with an African American art and artists.

Knight’s New Beginnings: In 1970 the couple relocated to the Pacific Northwest when Lawrence was offered a position as a visiting artist at the University of Washington. In these new environs, Knight was able to devote herself fully to her own practice and earned recognition for her often intimate and incisive portraits of the couple’s friends. Late in her life, Knight’s career blossomed and she received her first solo museum exhibition in 2003 at the Tacoma Museum of Art.

Loïs Mailou Jones and Louis Vergniaud Pierre-Noel

Loïs Mailou Jones poses for a photograph near a painting. Jackson State University via Getty Images.

International Harlem: Boston-born artist Loïs Mailou Jones and her husband Louis Vergniaud Pierre-Noel, an illustrator and designer born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, were both part of and shaped by the Harlem Renaissance. Jones, who was born in 1905, had gotten her start in Boston (she staged her first art show at 17 in her parents’ home in Martha’s Vineyard) and studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at night, but her distinctive artistic style focused on Black experiences began to take shape during her frequent summer trips to Harlem throughout the 1930s (Aaron Douglas particularly influenced her—many note her painting The Ascent of Ethopia’s stylistic kinship to Douglas). Paris was also pivotal to the artist, who traveled to France for a fellowship at the Academie Julien in 1937, where her interest in African and Caribbean visual traditions grew. Meanwhile, Pierre-Noel moved to New York in 1934, studying at Columbia University, then began a career in illustration, working frequently for the Natural History Museum. Here, in New York, the couple would ultimately cross paths and wed in 1953.

Graphic Arts Beginnings: Jones started her career as a textile designer after graduating from Howard University (she would teach at Howard on and off from 1930 to 1977). Though she ultimately focused on painting, her work would continue to celebrate graphic and decorative motifs. Pierre-Noel’s celebrated design sensibilities, notably, his embrace of bold colors and striking geometric shapes, also transferred into her compositions. Pierre-Noel was a well-known stamp designer, in addition to his work for museums, and he was commissioned by the Red Cross and the United Nations to design stamps.

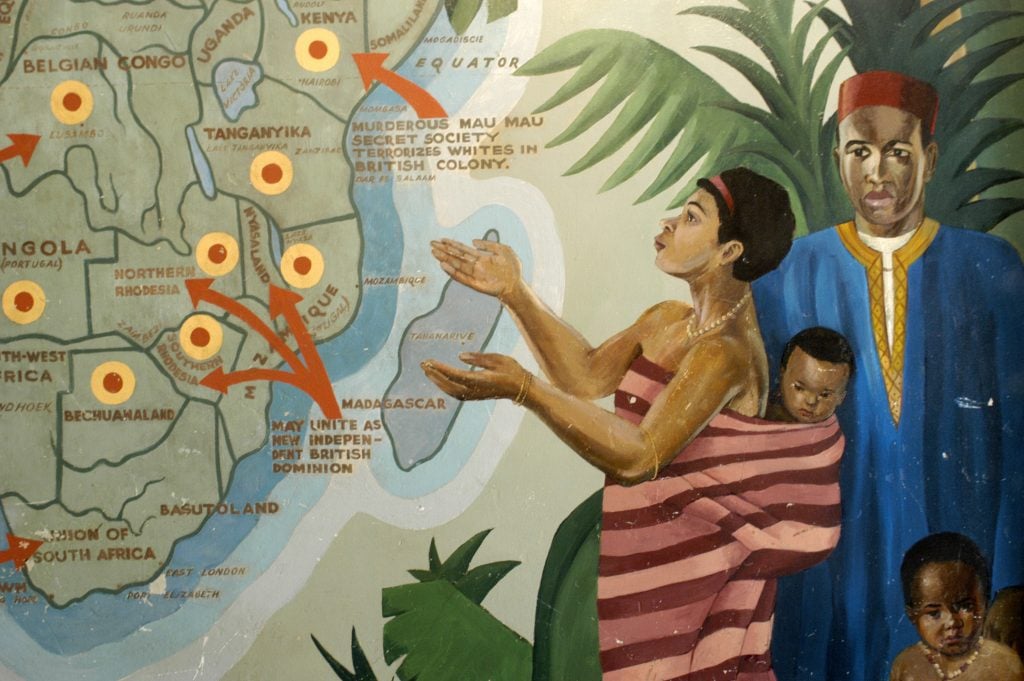

A mural by Lois Mailou Jones at the Sasha Bruce Youth Works, a center for homeless children, in Washington, D.C. Photo By Chris Maddaloni/Roll Call/Getty Images.

Caribbean and African Aesthetics: Throughout the decades of their marriage (the two remained married until Pierre-Noel’s passing in 1982), Pierre-Noel’s native Haiti and the wider Caribbean world would continue to shape Jones’ work. In 1954, Jones took a position as a visiting professor at the Centre D’Art and Foyer des Artes Plastiques in Port-au-Prince. Soon after, she would have a major showcase of 42 paintings in an exhibition sponsored by the First Lady of Haiti. During the 1970s, Jones served as a cultural ambassador to Africa for the United States Information Agency, traveling to nearly a dozen countries—experiences that heightened her focus on African imagery, including tribal masks, in her late career paintings

Romare Bearden and Nanette Rohan

Portrait of Nanette Rohan Bearden and artist Romare Bearden on their wedding day, (1954). Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. Courtesy of New York Public Library Digital Collections.

He Was Harlem Royalty—With a Day Job: Born in North Carolina, Romare Bearden moved to New York City during the Great Migration with his parents as a small child. Bearden’s parents were compelling personalities and his childhood home became an important hub for leading figures of the Harlem Renaissance. His father, Howard Bearden, was a pianist, and his mother, Bessye Bearden, was a dynamic figure in city policy, working with the New York City Board of Education and several philanthropic organizations. The Harlem community fostered the young Romare’s creative ambitions, and the artist’s early works often celebrated Harlem and its people. Nevertheless, opportunities for the artist, as a Black man in a largely white art world, remained hard-won. To supplement his income, in the mid-1930s, Bearden took a position as a caseworker for the New York City Department of Social Services, working in Harlem. It was a position he would return to intermittently throughout his life.

Romare Bearden, Profile/Part 1, The Twenties: Mecklenberg County, School Bell Time (1978). Courtesy of High Museum of Art.

Passion Across Mediums: Romare Bearden and Nanette Bearden (neé Rohan) married in 1954—bringing together two unique creative paths that would come to fruition together. Nanette, who was born in Staten Island, worked as a model, graduated from the Fashion Institute of Technology, and studied modern dance and jazz at the Martha Graham School and ballet at the Dance Theatre of Harlem. In the 1970s, Nanette founded her own dance company where she mentored a generation of dancers below her. Romare, meanwhile, would continue to develop his defining artistic language which straddled figuration, abstraction, and collage, while additionally writing several books. He was also a founding member of Spiral, a Harlem-centered art group that considered African American artists’ role in the Civil Rights Movement.

Eyes Ahead: Rooted in their experiences in Harlem, the couple nurtured a commitment to future generations of Black creatives. In the 1970s, Nanette founded the Nanette Bearden Contemporary Dance Theatre (later known as the NBCDT), a non-profit organization devoted to dancers, choreographers, and theatre artists of color, which would operate until her death in 1996. The couple also established the Bearden Foundation which supports young scholars and artists to this day.