Opinion

State of the Culture, II: From Post-Internet Art to Influencer Art to… Mystery Art

Looking back on the evolving artistic landscape of 2017, Ben Davis reflects on the mutations the role of the artist has undergone lately.

Looking back on the evolving artistic landscape of 2017, Ben Davis reflects on the mutations the role of the artist has undergone lately.

Ben Davis

In part one of this look back on the year, I talked about the evolving status of museums in the era of social media, changing audience habits, and the rise of Big Fun Art. Here, I’ll shift focus to how 2017 impacted the artists who help shape the discourse.

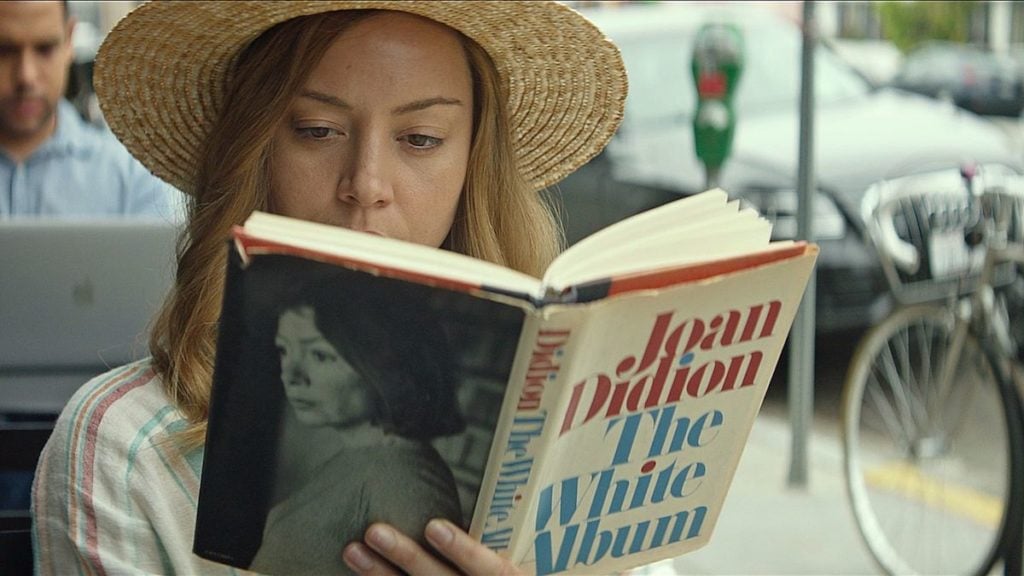

Matt Spicer’s film Ingrid Goes West will stand as a time capsule of the balance of cultural forces in 2017. It tells the story of sad-sack Instagram stalker Ingrid (Aubrey Plaza) and her obsession with fauxhemian LA lifestyle influencer Taylor (Elizabeth Olsen). Taylor’s husband Ezra (Wyatt Russell) is an artist who makes awful (but credible) social-media-inspired paintings: found canvasses with meme-ish slogans scrawled on them, including a herd of galloping stallions superimposed with the word “SQUADGOALS.”

What’s interesting is the complementary relationship between the Ezra-Taylor couple’s creative personae. Taylor, it is revealed, isn’t genuinely into the intellectual props that she studs her Instagram life with: Joan Didion, Norman Mailer, etc. Those, we learn, are Ezra’s tastes. She has simply appropriated them for their hipster cachet.

Ingrid (Aubrey Plaza) in Ingrid Goes West.

Ezra, on the other hand, is a social media abstainer—and yet his comically shallow art is completely under its sign. His first collector (Ingrid, of course) even comes via Taylor’s social media following. As personalities, the pair are symbiotic but in tension, with the influencer definitely in ascendance over the studio artist who, the film strongly implies, only maintains his critical posture as a defense mechanism to salve his feeling of being a hack to begin with.

The dynamics channelled by this artist-influencer couple are shaped by old gender stereotypes: “men act, women appear.” But the social standing of these terms in relation to one another has shifted. Taylor absorbs the outward signs of Ezra’s more traditionally “deep” aesthetic interests; but he gets everything, including link to an audience and even subject matter, from her.

Does this power rebalancing represent a kind of progress? Maybe—though overall, Ingrid Goes West is a parable of the creeping emptiness, destructive envy, and deformed incentives that this environment places on all involved—its female protagonist first of all.

Artists tend to have a lot of their self-identity wrapped up in being better than, wiser than, deeper than the ambient culture. And that means they can miss just how profound the experiences a wider audience is having outside their bubble.

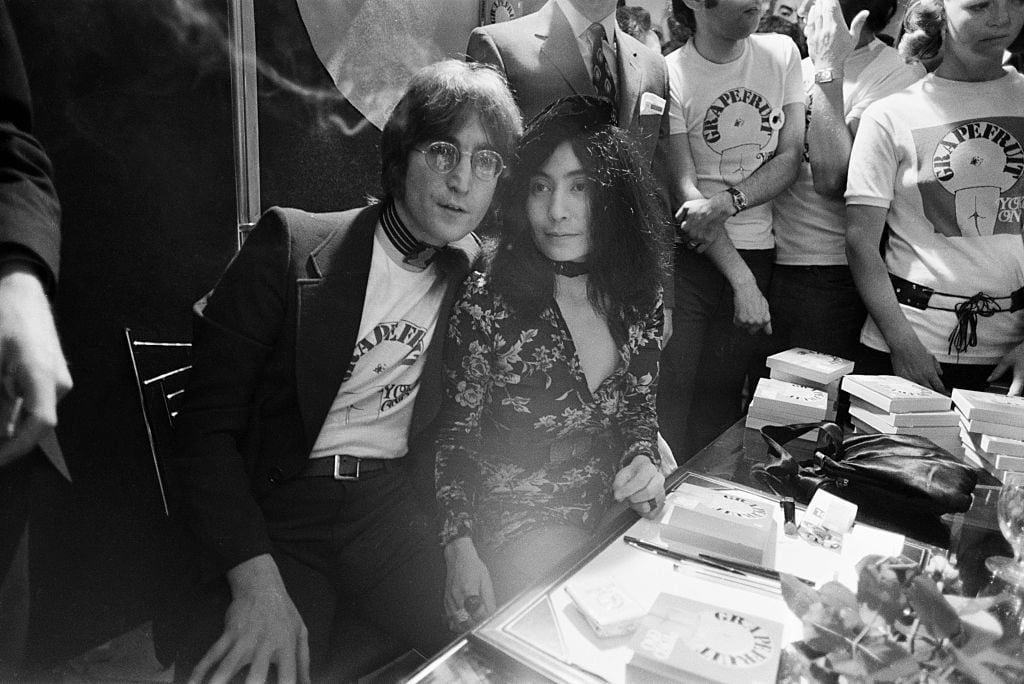

Back in the 1960s, while Beatles fans were vilifying Yoko Ono, her New York art-world friends were doubting whether John Lennon was a worthy match for her, a tidbit that now seems crazy given that Lennon and his musical peers are treated as cultural gods. “Yoko was a very important Fluxus artist,” Carolee Schneeman remembered. “And frankly, we all wondered if this… this… rock and roll guy was going to be smart enough for her.”

Singer and songwriter John Lennon with Yoko Ono, signing copies of her conceptual art book Grapefruit at Selfridges, London, 15th July 1971. Photo by Jack Kay/Daily Express/Getty Images.

Maybe the nose-in-the-air posture is a dated stereotype in a multimedia-fluent contemporary art world—though Ingrid Goes West caricatures it in Ezra’s pantomime of authenticity, which suggests otherwise.

The curator and critic Lawrence Alloway is often credited with coining the term Pop Art in the 1950s. The most interesting aspect of his thinking, however, is that he didn’t speak about “Pop” as a style of fine art. What he actually wrote about was what he called the “fine art-pop art continuum.”

That is, for Alloway, the point was that the world of pop culture and design and merchandise was itself already creative; you couldn’t create a hierarchy with “art” at the apex. It was a continuum, and a horizontal one. John on the same level as Yoko, plus all the John-Yoko stuff in between.

I think it might be useful to imagine a “fine art-social media continuum” along the same lines.

When, earlier this year, Cindy Sherman caused a stir by unlocking her Instagram to the public, the images were cool enough—but not really revelatory for their context, to my eyes. The viral excitement around them, it seemed to me, was really more that Sherman’s presence redeemed a general interest in the aesthetics of Instagram.

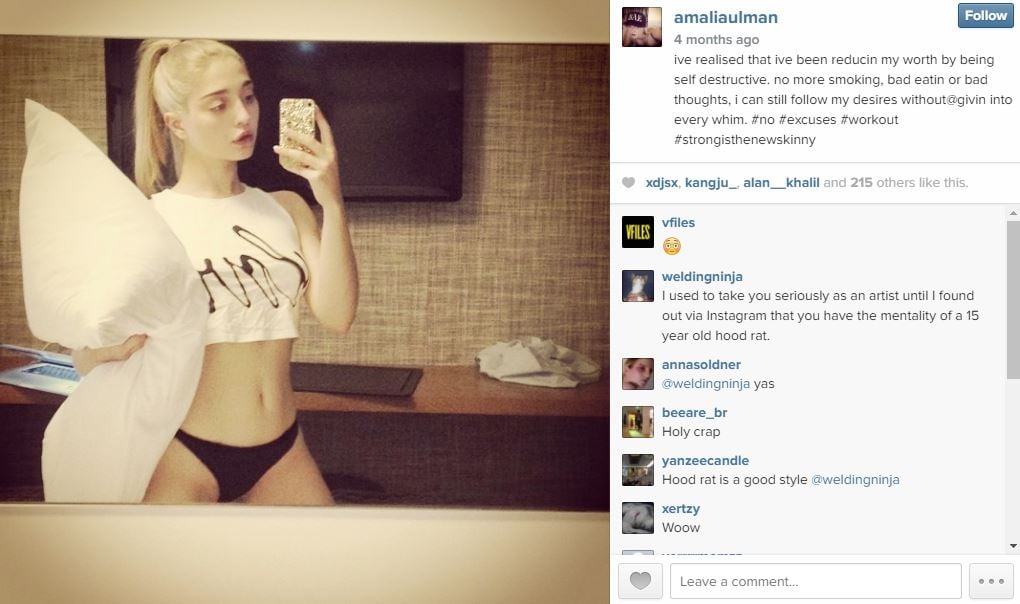

Still from Amalia Ulman’s “Excellences & Perfections” courtesy of Instagram.

For an example of someone treated as a “social media artist” within the art context, the go-to reference is probably someone like Amalia Ulman, who in 2014 unspooled a lightly seedy fake life story via Instagram, before revealing that it was all a performance artwork dubbed Excellences & Perfections. Elle would dub Ulman “The First Great Instagram Artist.”

Or you might also think of Petra Cortright. She is now a painter (and designer of Google phone cases). But she first managed to win the notice of art observers by baffling them with inscrutable, affectless webcam videos on YouTube—some kind of early commentary on the isolation of the screen.

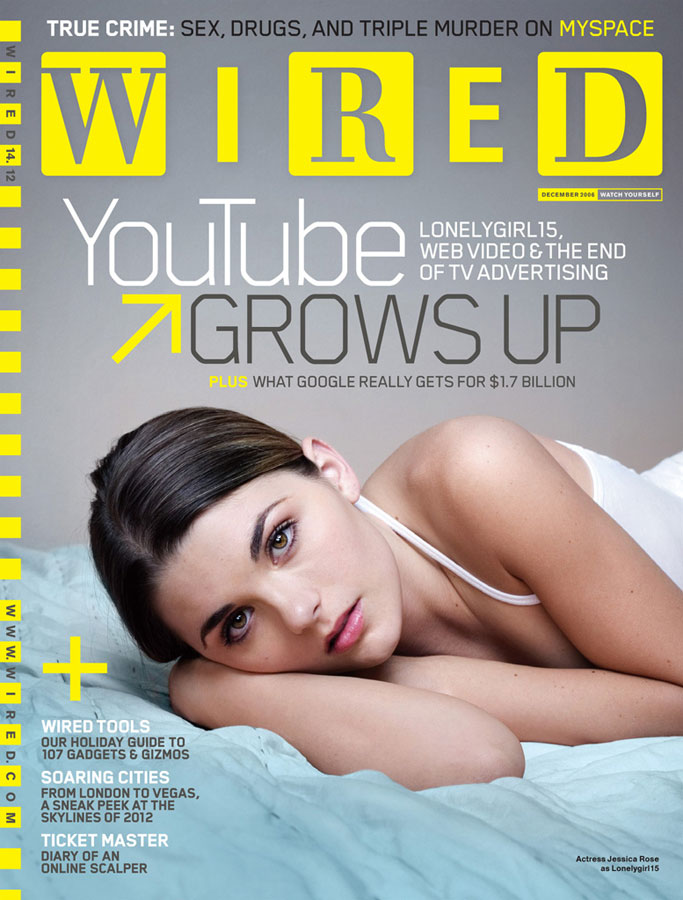

Looking at such figures from outside the slightly credulous gaze of the art world, I have difficulty seeing how such works will last. A decade ago, at the dawn of YouTube, the personality called Lonelygirl15 developed a giant following for her winsome personality. Gradually, her monologues revealed a story about a mysterious cult. Then it was all revealed to be an elaborate scripted hoax. It merged the video diary format and fabulated narrative many years before fine art was watching that space.

Some 110 million people have viewed Lonelygirl videos overall. Lonelygirl made the cover of Wired magazine with the teaser “YouTube Grows Up,” becoming one of the faces of that platform blossoming into the immense ecosystem of vloggers, pranksters, and viral para-art that it is today.

Judged by any external standard—formative influence on the medium, actual popularity, complexity of execution—Lonelygirl15 is the project that belongs in the Museum of Internet Art. The idea that the artists did something richer because they are, formally, “artists” is untenable.

More recently, the art/social-media ecosystem has spawned a new intermediary character, somewhere between socialite, photo diarist, performer, and artist. A much-followed example is Pari Ehsan, aka @Paridust, an architect turned fashion blogger who a few years ago had the inspiration to begin pairing her clothing with the art at shows she was seeing, posting the images to her website and Instagram.

Over the last few years, Paridust has accumulated 200,000 followers—modest for an Instagram influencer, but equal to the following of Ulman’s now-canonized Excellences & Perfections performance twice over and then some. She has won media coverage to make most artists envious, and now peppers the gallery-going fashion adventures of her feed with #ads for Uber, Volvo, and Calvin Klein Obsession.

As a role model for a new generation of creative people, Ehsan is almost certainly more potent than most contemporary artists. What she does is Influencer Art avant la lettre.

“Disintermediation” is a hot word in the business world, with all manner of startups making the bet on cutting out middlemen. Get rid of brick-and-mortar; sell direct; keep the savings. And, with a chronic oversupply of artists and the gallery model creaking, plenty of people are betting on social media tools to allow artists to be their own agents—combining, in effect, the two meanings of self-representation.

This year, the list of articles marveling at figures who owe some kind of success to Instagram grew (see Baron von Fancy, or Lauren Brevner), to the point where the novelty of the trope might be wearing off.

None of these have really achieved the kind of art-world success, yet, that Bodak Yellow sensation Cardi B achieved in music this year, from her Instagram launchpad. This may be because the art industry is too invested in maintaining the authority of its own arcane structures; or it may be because the social media platform inherently favors people who are attractive performers.

Indeed, it is notable that even the most conventional types of artists are pressed towards a new sideline as a performer within the Fine Art-Social Media continuum. The Nashville painter Shane Miller, creator of woozy encaustic landscape paintings, became something of a spokesperson for the self-repping Instagram art scene this year. Here he is, speaking to the State of the Art podcast:

I think people crave that connection with the artist, and with the art. Obviously, art speaks for itself…. But I think people appreciate knowing what is behind the piece, or what the artist is thinking, or even just what the artist is thinking aside from when they are in the studio. What does the artist do outside the studio, or outside of painting? Who are they as a person? I think that’s something that is new that before the internet wasn’t a thing for the artist. They would stick to the studio and the gallery would be the middle man, and there was this air of mystery surrounding the artist.

My colleague, Tim Schneider, doubts that disintermediation will become quite the democratizing savior artists hope, because of what he calls the “tyranny of options”: without gatekeepers, the number of artists competing in the same space multiplies, actually diminishing the odds of profitable success.

But for those hustling for a shot at the brass ring within the new environment, the pressure to stand out intensifies—which means the pressure to become a human brand grows, and visual artists sprout a new sideline performing themselves.

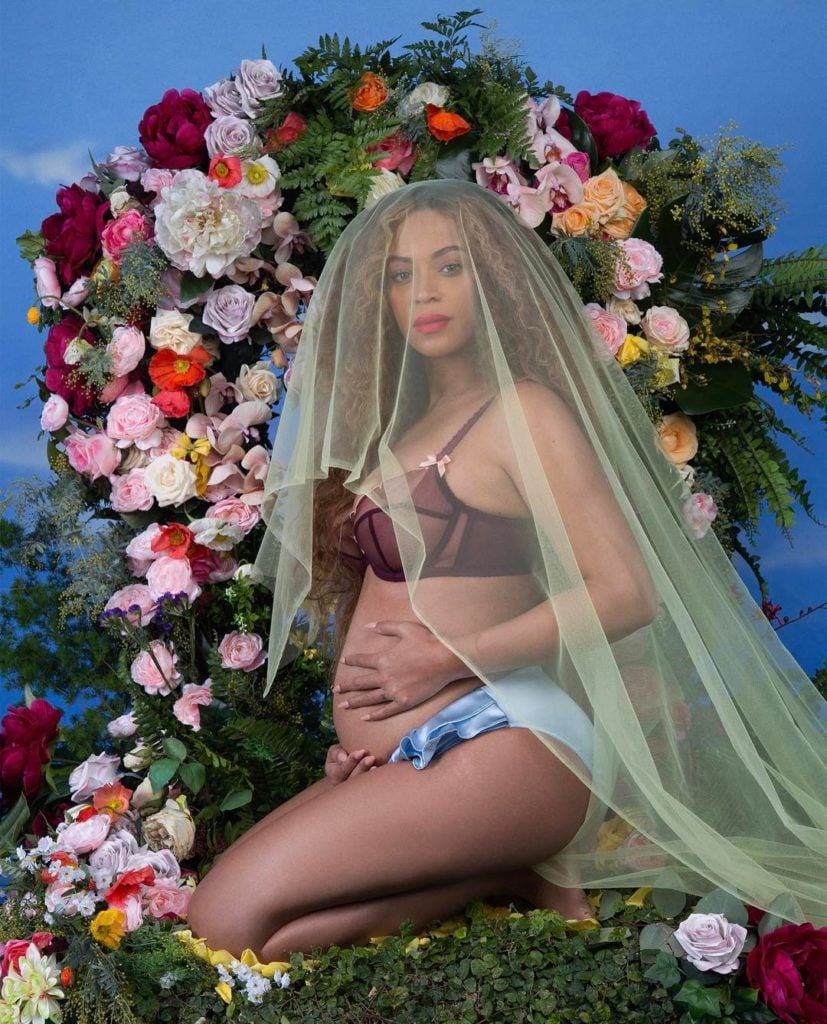

The most-viewed artwork of the year, by almost any standard, is Awol Erizku’s flower-bedecked maternity portrait of a pregnant Beyoncé. On Instagram, its posting marked her official announcement that she and hubby Sean Carter had been “blessed two times over” with twins. It was the most-liked photo of the year on the platform.

Awol Erizku’s Beyoncé pregnancy announcement photograph. Photo courtesy of Beyoncé, via Instagram.

I freely admit that Influencer Art brings out the inner Adorno in me. The entire phenomenon of collapsing life into an ad for your life into a just-plain-ad stinks of capitalism flattening aesthetics and subjectivity at a whole new eerie and toxic level.

But Instagram has been a way to create buzz about a pool of voices who otherwise wouldn’t be taken as seriously. Given all the biases that infest the art system as it is, that’s not a bad thing.

Erizku is a good example of a worthy artist who has caught fire through this channel. Even if you count the maternity pic not as a pure work by him, but as some kind of Erizku-Knowles co-creation, the connection gave his art a new prominence (even if he himself maintains the traditional fine-art aloofness, preferring not to talk about the Beyoncé connection). If artist-designed celeb society portraiture becomes a thing, I am pro—or at least not by-default anti.

Still, the Erizku pic’s success also points to another dynamic of the space as a platform for artistic identity formation. There are definitely figures who hustle their way up the ranks of the art-influencer economy through pluck. But for all social media’s purported democracy, in the art case some pre-established celebrity or brand almost always plays a part in solidifying real success.

Most Instagram success stories have this character. For the psychedelic self-portraitist Bex Ilsley, it was an association with Miley Cyrus. For Harmonia Rosales, who went mega-viral this year after repainting the Sistine Chapel with black women as its stars, every article recounts her celebrity fans, including Samuel L. Jackson and Amar’e Stoudemire.

So far, the evidence suggests that disintermediation may not so much as do away with gatekeepers for art, as shift the credibility-establishing function from the realm of art-specific experts to mass-appeal celebrities.

To get a sense of the more unseemly pressures at play in the space, we might have to seriously consider the success of another set of twins, Allie and Lexi Kaplan, aka the Kaplan Twins.

After getting BFAs at NYU as painters, the duo first found viral success with lightly stylized, but basically photo-derived canvasses depicting racy celebrity selfies—a kind of hack for the requisite famous-person association. They found their first major financial and media heat when the adult-video aggregator Pornhub bought their painting of a still of Kim Kardashian’s sex tape for its offices.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BXOdTxrgjc3/?hl=en&taken-by=the_kaplan_twins

The Twins then went West, to Los Angeles. They have moved towards explicitly thinking of themselves as hybrid artist-celebs, half-Warhol and half-pornier performance-art Mary-Kate and Ashley. “In New York, the art world is set in its ways,” they explained to Vice. “Here is untapped. There’s Hollywood, and it’s easy for artists to merge into that culture for us. That’s why Instagram is such a good tool for us, because we integrate ourselves into our work.”

In LA, they met (via Instagram, of course) Matty Mo, an art agent/guru known as The Most Famous Artist. Mo (I cannot bring myself to call him The Most Famous Artist) explained his philosophy to Vice, offering a brain nugget that nicely sums up how their evolution reflects a natural slide along the Fine Art-Social Media continuum:

I come from the Silicon Valley world and now I am looking to disrupt the art world. Almost immediately we started to think of ideas of how we can monetize their brand in the environment which is direct-to-consumer art sales on Instagram. They made this interesting observation that they got a lot more likes on photos of themselves than they did of their artwork. And so we got to think about how we could integrate an art object into their lives and tell the stories of their involvement with the objects and sell it directly to consumers.

Such an inspiration resulted in Boy Toys, a performance for which they photographed themselves sleeping with various stuffed animals, then sold them as found-object sculptures to their followers. Their next inspiration was their “#SATONYOURFACE” collection, prints which involved them painting each other’s butts then pressing them to illustrated faces of Marcel Duchamp, Mr. Brainwash, Donald Trump, and so on. The Twins performed a version in Miami during Art Basel Miami Beach this year—DuJour mag called them “up-and-coming pop-artists”—ratifying that event’s status as the pile-up of charmless dumbassery that it has become.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bcf8aMlAt2h/?taken-by=the_kaplan_twins

Social media has done a lot of good, politically, giving a platform to marginalized voices. But simultaneously, it has helped an authoritarian multimillionaire reality TV show star to become “Twitter president.” It undercuts old hierarchies but also amplifies embedded privileges—sometimes both at once, in the Trump case. Influencer Art opens new pathways to success but, given a ruthlessly unequal environment, it probably creates incentives that favor the conventionally attractive, the wealthy, the well-connected.

As art’s evolution continues apace under its star, it is bound to force us to take some very, very grotesque things more seriously than we would ever have wanted to.

For all my visceral dislike of its dead-eyed cynicism, it’s not that the Kaplan Twins phenomenon somehow does not belong on the continuum with “art.” It’s simply bad art.

Like Ingrid at the end of Ingrid Goes West (I’m not going to spoil it), it embodies a mindset that can no longer tell the difference between creative success and the most destructive and fleeting forms of attention. What the Kaplan Twins offer is so clearly basic titillation that I can’t imagine it not being discarded by the very appetites that it stokes, since those appetites are so superficial.

For the purposes of understanding the emergent skillset of Influencer Art, you might look to another artist, the enigmatic figure known as Zardulu, the Mythmaker. A masked and inscrutable force, she first became well-known for Selfie Rat, a viral hoax in New York, though supposedly she was working in the shadows well before that. (The spreading Zardulu mythos is chronicled in a crackerjack episode of the podcast Reply All.)

Like the Kaplan Twins, Zardulu was in Miami for fair week this year. There with the help of drag queen and artist Gio Profera, she perpetrated another hoax, this one finding its way onto Telemundo and being crowned “[o]ne of the most widely viewed pieces during Miami Art Week” by the New York Times. In the clip, a man is seen declaring that he has just been bitten in the testicles by an iguana that came from the toilet.

Zardulu calls the work The Usurpation of Ouranos.

I’m not so sure I think such a gesture is by itself that clever—though I love the idea that the improbable but not-so-improbable happening was meant to echo (on some buried level) Greek myth, with the iguana standing for the avenging god Kronos.

In the post-truth political landscape, this kind of hoax-art does risk eroding any credible sense of reality. The cultivation of fake wackiness also has the effect of eroding attentiveness to the genuine eerie coincidences in the world.

Nevertheless, there is something to learn from Zardulu. She has, thus far, managed not to give up her secret identity to the media. That withdrawal is very clearly theorized as part of the art. “Deep down,” Zardulu told the Times, “we don’t care about the truth. We want myth.”

And while this calculated enigma is of course a ploy to feed a media myth (oddly, in this sense, her methodology most echoes Banksy), it also pushes deliberately against the tendency of social media to consume the personality of the artist. The pressures of that media space all push artists to be relatable objects of desire (“Who are they as a person?”, is what Shane Miller thinks his collectors want from an artist on social media). It tends to exhaust viral fascinations by relentlessly denuding them of whatever mystery or novelty powered them in the first place.

What sets Zardulu aside from the average viral media hoaxster is her refusal to finally be known, to totally explain the joke, to totally give up the secret to the gaze looking in. That’s actually a very difficult balance beam to walk.

The ability to feed the hunger of the image machine but not let it totally consume you may be the artistic skill of the future.

Which brings us to the importance of interpretation—which will be the subject of the last part of this series, on the changing status of art writing, which will have to wait until the New Year.