Opinion

It’s War! Kenny Schachter on the Brewing Art-Fair Battle to Control the Supply Chain

Things are getting ugly out there, our combat-grizzled columnist reports.

Things are getting ugly out there, our combat-grizzled columnist reports.

Kenny Schachter

There is a gathering storm in the art world, and already the threatening clouds of an art-fair land war can be seen flashing over the Rhineland. To whit: the MCH Group, the Swiss parent of the Art Basel fairs, has thrown down the gauntlet by launching a series of regional fairs, beginning with a foray in Düsseldorf meant to take on the venerable Art Cologne. The fallout will be far reaching. In turn, Cologne has announced a merger with abc Berlin—or with GWB Veranstaltungs UG, to be exact, the group of gallerists that also initiated Gallery Weekend Berlin in 2005. Look for further consolidations in the field to follow.

Rather than Janson’s History of Art, earnest art-class syllabuses should now include The Art of War, Sun Tzu’s ultimate 5th-century BC manual on military tactics and strategies. The gloves are off in the normally taciturn art world: forget the Ultimate Fighting Championship (formerly the property of the art-investing Fertitta brothers), we are about to enter the midst of a whole other variety of no-holds-barred warfare.

Here is the lowdown on the art-fairs showdown: we are in a market phase where galleries are mere cogs in an overarching global fair machine, which has become the predominant platform to showcase and direct-market art (with Instagram as the unwitting media partner). And, undeniably, the fact that fairs are now the art world’s supply chain has had a Darwinian impact on the art. These events are increasingly shading a significant portion of what gets made in the form of art-fair art, a genre of works that are compact, portable, domesticated, and generally cheerful in content. Or, of late, cheekily political.

The art is getting stuck in an endlessly repeating treadmill and can’t get off the cycle, like itinerant migrant workers. And existing events continue to spawn further fairs, like asexually reproducing hydras. Trawling the tents and convention halls has become an experience akin to being lost in front of a slot machine in a casino—there’s no sense of time, and you lose track of everything other than the art and the people pushing it.

Donning my flack jacket to investigate—and, yes, participate in—the latest volley of art fairs, I headed out once more unto the breach.

Cologne is a bit of a depressed, melancholic city, but it’s also host of the original contemporary fair, Art Cologne, which was established in 1967 (three years before the first Art Basel). I got my spiritual art start in the city in the 1980s and curated my first show, “German Paper,” in 1990 at Sandra Gering Gallery in New York. I also served on the selection committee 10 years ago before the head of the fair at that time, Gérard Goodrow, was overthrown in a virtual coup—but that’s another story.

Jaywalking is not an option in town without authoritarian recriminations, i.e., being ticketed. In the same vein, I spotted seven art pieces at the fair incorporating fences, including ones by Cady Noland, Rudolf Stingel, and Gerhard Richter—works earmarked for a country that takes matters of control very seriously, still. Art Cologne is a relatively sleepy affair but I prefer it that way, not having to trip over every overexposed art advisor and pseudo collector.

The battle lines are drawn, and painted (by Gerhard Richter, in

Zaun (Fence), 2010). Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Dealers range from old workhorses like Jurgen Becker, an ex-lawyer and art collector who exhibits artists like Joseph Beuys, Sigmar Polke, and Richard Tuttle, to upstart Ginerva Gambino, the made-up name of Laura Henseler’s new emerging-art space in Cologne. Henseler took part in a subsidized portion of the fair that encourages collaborations between artists and dealers. Nevertheless, as an illustration of just how hard it is for small galleries, dealers can still lose money even if they sell out the contents of their booths.

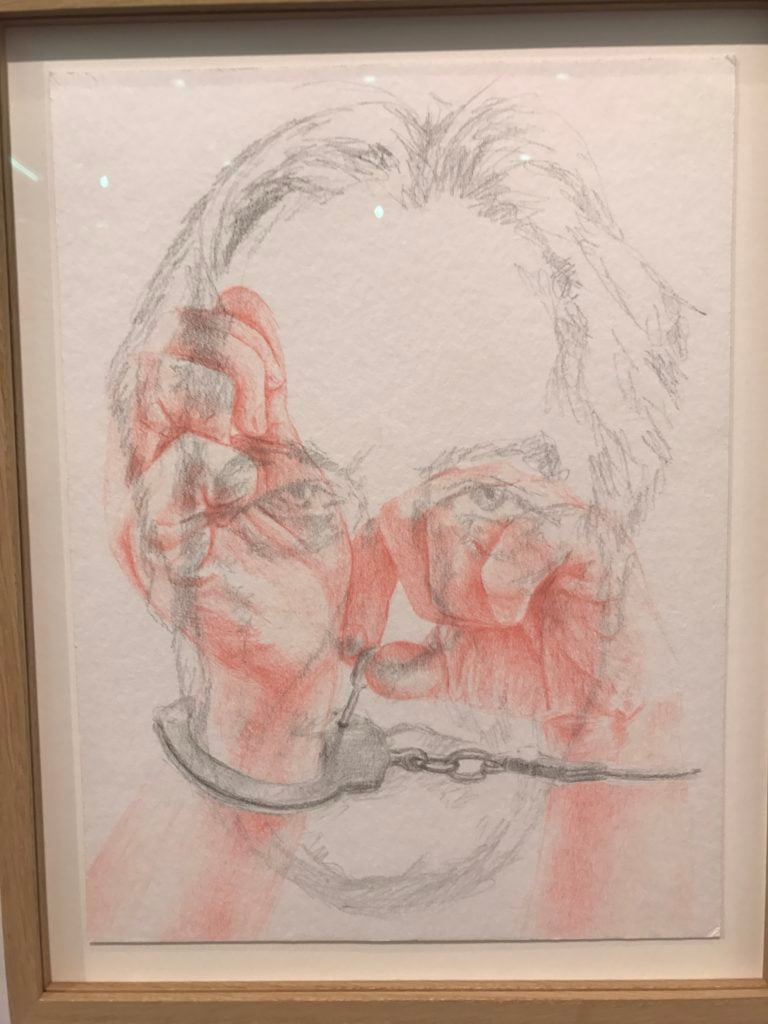

Ginerva Gambino did just that with the presentation of Alex Wissel, a 34-year-old artist who presented drawings based on Helge Achenbach, an art dealer who served jail time for defrauding his clients. In what could serve as a cautionary tale, Achenbach admitted to replacing euro for dollar symbols in invoices to embellish the prices he charged clients, thereby raising commissions he was owed. Wissel also created a film depicting Achenbach meticulously cutting and pasting his paperwork (in a time prior to Photoshop) and making entreaties to the ghost of Joseph Beuys: “But you said everyone is an artist!” I’m a (digital) collagist myself and can appreciate the dexterity and industriousness involved in such a task.

Alex Wissel’s Untitled (From the Series Rheingold), 2017. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Babette Albrecht, the widow of the late billionaire and Aldi supermarket heir Berthold Albrecht—the chief victim of Achenbach’s creative accounting—turned up at the booth with a journalist from gossip magazine Bunte and wanted to be photographed buying one of the drawings that featured the Aldi logo, but the gallery refused. Undaunted, Babette loudly protested: “That’s mine! I want to buy it!” After repeated threats, she retreated. Though Achenbach has since been released from prison, he’s paid his dues by serving time and losing his business and his wife in the process. The widow has launched another suit against him. Babette should back off.

After braving the whizzing market bullets of one art-fair battleground in the Rhineland, I flew off to another major hotspot in the simmering international fair wars, New York.

Believe it or not, I can remember a time when there was but one Art Basel and New York’s Armory Show was a fetid flea market in a derelict hotel. Other than a small handful of provincial events, that was about it on the fair front. Those days are far behind us. I had sworn off going to this year’s New York spinoffs of London’s Frieze Art Fair and Maastricht’s The European Fine Art Foundation (TEFAF), since I’m already due in town for the big May contemporary auctions nearly two weeks after—but, like a fly drawn to shit, I couldn’t resist.

Upon arriving, my phone made a horrifying, unfamiliar buzzing sound that turned out to be a flash-flood warning. My luck: I leave rainy London only to face a New York deluge of biblical proportions that resulted in the Annabelle Selldorf-designed Frieze tent springing multiple leaks and a temporary suspension of public transport to the fair.

Also my luck, in a non-sarcastic way: I brought along Adrian and Kai, two of my sons who are studying art at New York’s School of Visual Arts. My aim was to not forget about them amid the whirl of the art-fair calendar, and, for another, to help introduce them to people in preparation for an upcoming exhibition they’re staging (read on). They got an earful—and more!—from my acquaintances asking me not to record our conversations. Yet fear not readers, I wouldn’t let you down. For future reference, here’s a warning: I’m a reporter with less than total self-control, so if you don’t want me to write it, please don’t tell me.

TEFAF, established in the Netherlands in 1988, went on the offensive against the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA) fair by sneakily bivouacking in very same venue, the Park Avenue Armory, an 1880 Gothic Revival building that served as headquarters for the 7th New York Militia Regiment. According to Wikipedia, the Armory was known as the Silk Stocking Regiment due to the lopsided number of members who were part of the city’s social elite. The crème de la crème made their way back in droves, but the only trace of combat were the repeated slashes in the glut of Lucio Fontana paintings that dotted booth after booth, a bona fide currency in today’s market.

TEFAF deliberately struck hard at the ADAA, employing a shock-and-awe maneuver by opening up various period rooms and semi-exposing magnificent architectural details of the building. Besides the one-stop-shop fare on hand—including furniture, jewelry, and antiquities—TEFAF’s chief innovation was the introduction of wall labels incorporating price tags; positively revolutionary! I could save years of my life not having to ask.

New York is a time-challenged city—there’s so much to see that there’s never enough of it—but moving through any fair brings all sense of haste to a halt. I spent a full five hours wandering around Frieze, but it still managed to be enervating despite the energetic invective of gallerist David Kordansky of Los Angeles. I previously wrote about how the dealer had condescended to a potential buyer last Basel, and when he saw me he struck back in no uncertain terms (which I can only appreciate).

In his booth, in front of my kids and several clients, Kordansky sounded off to the effect that my words were untrue (they weren’t) and how hurtful it was to him. His reaction was a snarky mix of annoyance and histrionics delivered in a detached, discomfiting, deadpan tone and ended with the distinctly LA admonition that he was a sensitive yoga-practicing vegan. I’m sure he was playing me in front of my friends and family—but, in all seriousness, he’s wildly successful and I’m acutely aware how hard that is and how steadfast you must be to maintain it. By the way, he had some fantastic works on hand by Tala Madani ($30,000-70,000) that a friend described as paintings of clumsy, lost men by a powerful, funny woman. I think I’ve grown to like Kordansky. Namaste.

Adrian, Kai, and Caio (with Kenny) at Frieze New York. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Artist Dora Budor was commissioned by the fair to stage a public performance and, in doing so, hired three Leo DiCaprio lookalikes to traipse the aisles dressed as characters from the actor’s films. According to one Upper East Side dealer—often Leo’s consort at such events—the actor had refused to attend. Perhaps fair management might reconsider their commissioning policies. I can be my own worst enemy (and frequently am) but even I wouldn’t stoop for some easy publicity with a piece that wasn’t very good or interesting to look at. As critical as I am of Leo’s famously short attention span when it comes to keeping the art (more like flipping fodder) he buys, it’s still idiotic to alienate a patron. And who could blame him? He’d be selfied to death. DiCaprio did go to TEFAF, and I’m not sure what he bought, if anything, but it surely will be back on the market again soon if he did so.

Waiting for an Uber, the only exit strategy from Randall’s Island, credulity is tested where five minutes waiting time on the screen is stretched to a seeming eternity, in essence distorting the space-time continuum. After spending such an inordinate amount of time in the tent, I gave short shrift to 10 percent of the art due to fatigue. But the inconvenient location doesn’t lend itself to revisiting.

Following the fair, I caught an incredible Rachel Harrison exhibit at Greene Naftali gallery. I began working with Rachel back in 1990 and she’s evolved into one of the most formidable sculptors of her generation. Beneath her deceptively playful biomorphic blobs lies a rigorous sense of formalism. Fun and funny yet deadly serious, they are ambiguous in meaning and simultaneously have a built-in narrative. The works are like Richard Serra on MDMA and/or Franz West with a spritzer. Throughout the enterprise, there is an underlying lively mischievous humor that is both punning and cutting.

Rachel Harrison’s Greatest Hits, 2017. Wood, polystyrene, cardboard, burlap, cement, acrylic, synthetic hair, dolly, engineered quartz, trigger clamp, Museum with Walls catalogue, sketchbooks, plastic cup, paintbrushes, and lead shot. Courtesy of Greene Naftali Gallery.

I also visited the not-to-be-missed Brian Belott show (who I also previously exhibited in 2004) at Gavin Brown’s gargantuan new Harlem gallery. The raw, epic space nicely bookends Thaddeaus Ropac’s recently opened lavish London digs. These mammoth galleries reflect monumental leaps of faith—they are both rental properties and reflect profound commitments to sustaining an operation. When I profusely complimented Gavin on the accomplishment, he smugly agreed with me. I love the art world… I do!

My nepotism in support of my artist kids knows no bounds, and would give Trump a run for his money—but hey, they still sink or swim according to whether they are any good (and they are). On May 19th, Adrian and KaI will open a show with Caio Twombly in a partially emptied though still operative chiropractic clinic; the show is titled “Slipped Disc.” After so much writing (I take notes on my phone, since my Blackberry days) and social media-ing, I am developing iPosture, folding in on myself like a potato bug (or pill-bug)—I should book a chiropractic session at the opening. (Although it would be a convenient way to see fairs, being rolled down the aisles.) I fully appreciate how damn fortunate I am to have coinciding spheres of interest with my children to the extent we do. I can’t wait to return to New York next week for what is sure to be a sensational show (and slate of auction sales).