Art Criticism

What I’m Looking At: A Bawdy Zodiac, Vaping Frogs, and Deceptive Patterns

Picks from New York galleries from the last few weeks.

Picks from New York galleries from the last few weeks.

Ben Davis

“What I’m Looking At” is a semi-regular column where I digest art worth seeing, and share whatever else is on my mind. Below, thoughts on what’s in the galleries in New York, November 2024.

Jerome Caja, “Ugly Pageant” at Bortolami Upstairs

From what I understand, Jerome Caja (1958–95) is best known as a drag performer and for his association with the Queercore scene in San Francisco, a raucous splinter of punk. This trove of very fun little artworks at Bortolami is flush with DIY energy and rough humor.

Sometimes the works’ lusty, cartoony style makes me laugh out loud, even as it feels very intimate and almost confessional. They have names like Betty in a Bear Trap (1991), Virgin Poop (1992), or The Birth of Venus in Cleveland (1988), and were generally made out of what was close at hand for Caja (the medium of that last one is “nail polish on tip tray.”)

If there’s a work that stands out here, it’s probably The Zodiac (1994), a macabre and debauched take on the astrological signs, each imagined as a different, cheerfully unholy coupling.

Jerome Caja, The Zodiac (1994). Image courtesy Bortolami.

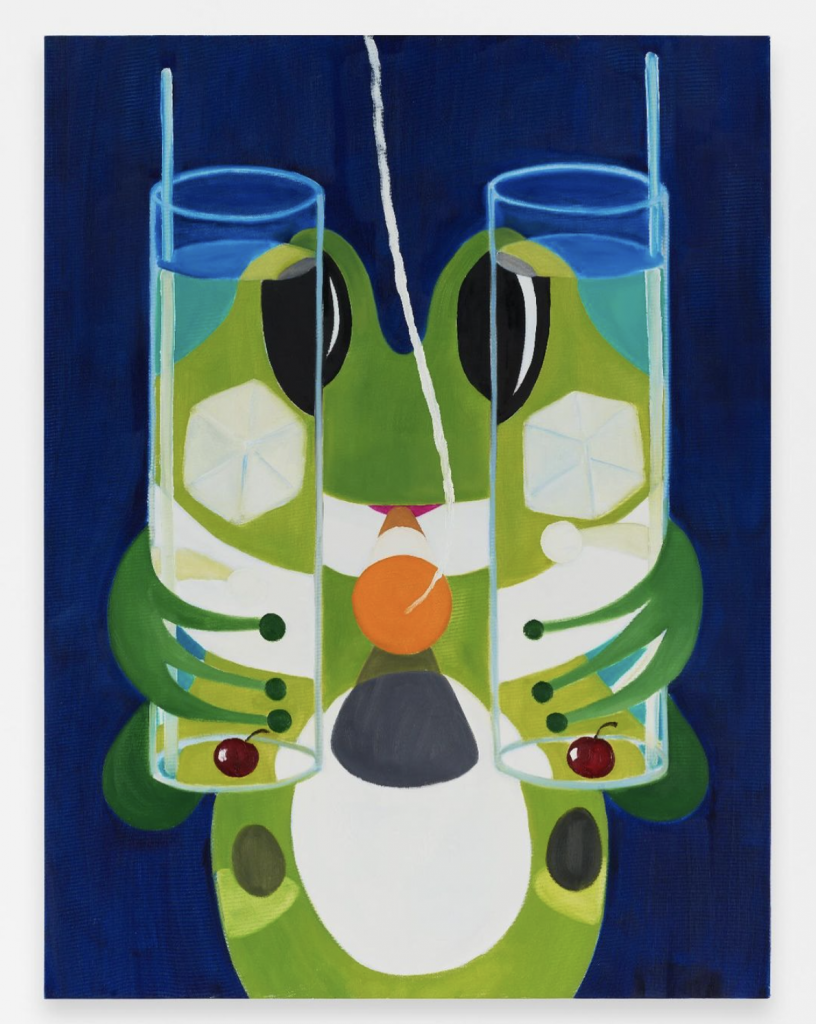

Keith Boadwee, “How Much is that Froggy in the Window?” at Anton Kern Gallery Window

“I used to worry my tombstone would say, ‘Here lies Keith Boadwee, the butthole painter,’” the Emeryville, California-based artist (1961–) is quoted as saying on the gallery’s website, explaining his artistic journey, “but I think people know me better than that now.” (I’ll admit that I first heard about Boadwee as a formative influence on the painter called CumWizard69420.)

And indeed, based on these canvasses on view in the “window” space of Anton Kern, it’s possible that Boadwee’s literally balls-out earlier work will be the Pink Flamingos to this newer body of work’s Hairspray. This suite of paintings centers on cartoon humans and humanoid frogs, often smoking or vaping, united usually by the way they stare out at you with big, druggy eyes through the distorted surface of water in a fishbowl.

It feels like Boadwee is grounding his warped perspective in a literally warped perspective. The paintings are—there is no other way to put it—cute, but they keep a slightly off-kilter, shot-from-the-brain quality that makes them stick with you.

Keith Boadwee, Being and Nothingness (2024). Photo by Ben Davis.

Keith Boadwee, Double Fisting (2024). Image courtesy Anton Kern.

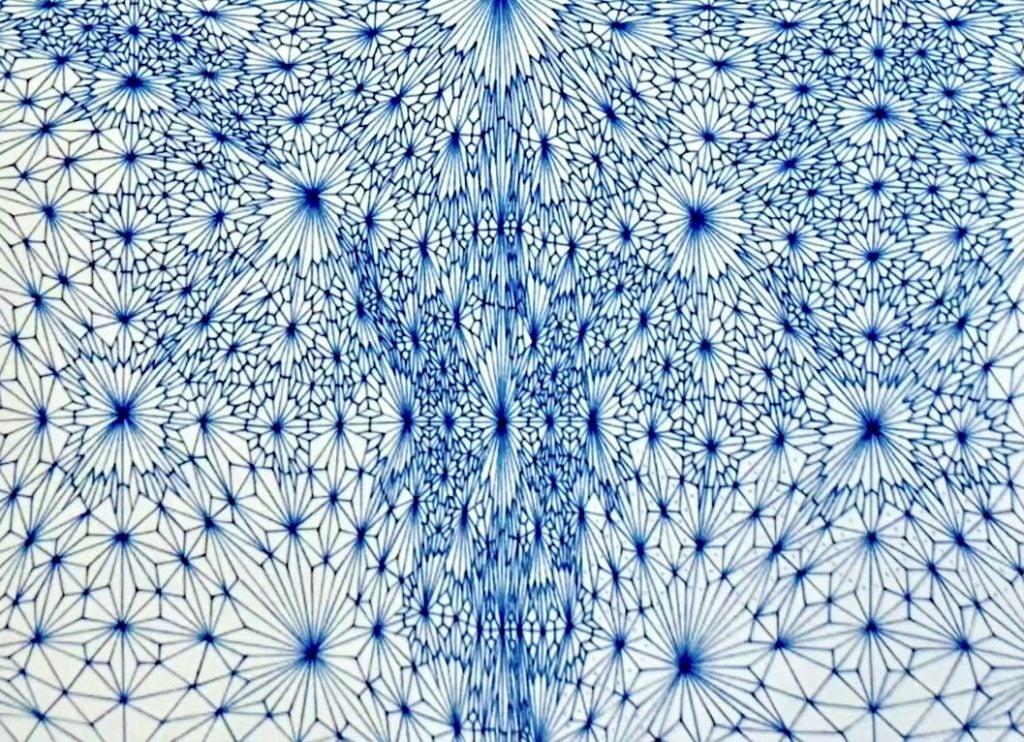

Richard Tinkler, “Monochromatic Drawings” at 56 Henry Street

Richard Tinkler (1975–) builds up these drawings by working outwards from the center, elaborating dense pattern step by step by step by step by step by step by step. Eventually, you get these compact, wonderfully intricate abstractions, each basically using a single color of ink. Their almost computer-like discipline is what registers first—but sitting with them just a moment, it becomes clear that “the center is never in the actual center and nothing is really symmetrical,” as Tinkler writes.

The little glitches take your eyes a second to dig up, because he’s very precise. But they are there, and, as he says, important. They make them fun to look at in a spot-the-difference kind of way. But more importantly, they make the all-at-once pleasure of the patterns read suddenly as the accumulation of little decisions. At any rate, the finished works convey to you, as a viewer, some of the almost ego-less meditative pleasure that must go into that painstaking process. Very satisfying.

Installation view of Richard Tinkler, “Monochromatic Drawings” at 56 Henry. Image courtesy 56 Henry.

Richard Tinkler, Book 11 Volume 1 Page 24.2 (2024). Image courtesy 56 Henry.

Richard Tinkler, Book 11 Volume 1 Page 24.2 [detail] (2024). Photo by Ben Davis.