Opinion

Why It Matters That Jimmie Durham Is Not a Cherokee

The principle of self-representation is profoundly important.

The principle of self-representation is profoundly important.

America Meredith

Clearly exasperated with the recent flurries of online discussion about Sam Durant’s Scaffold (2012) and now about Jimmie Durham’s retrospective at the Walker Art Center, the Zuni-Navajo artist Demian DinéYazhi recently posted a request on Facebook: “Every time you post about Sam Durant or Jimmie Durham, how about you follow it up by posting about an Indigenous artist who deserves the same energy and signal boost?”

Every day I post and write about Native artists. That’s my job, and something I love doing since there are so many compelling Native artists whom the world should know about. But the ignore-him-and-he’ll-go-away approach has not worked or done anything to stanch the steady flow of articles, essays, and books positioning Jimmie Durham not just as a Native American, but the Native artist that the rest of us would do well to emulate.

In January, Los Angeles’s Hammer Museum launched an ambitious traveling retrospective, “Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World,” which just opened at the Walker and will continue to the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Remai Modern. I waited and hoped for someone else to voice a protest, but finally James Luna (Luiseño), Nancy Mithlo (Chiricahua Apache), and myself all realized we had to speak up.

Fortunately, Minneapolis has an incredibly organized, tight-knit Native community, and Heid and Louise Erdrich (Ojibwe), Dyani White Hawk (Lakota), and Rosy Simas (Seneca) met directly with Olga Viso, director at the Walker, and Anne Ellegood, exhibition curator. Meanwhile, Ashley Holland (Cherokee Nation) was also researching Durham’s false Cherokee claims.

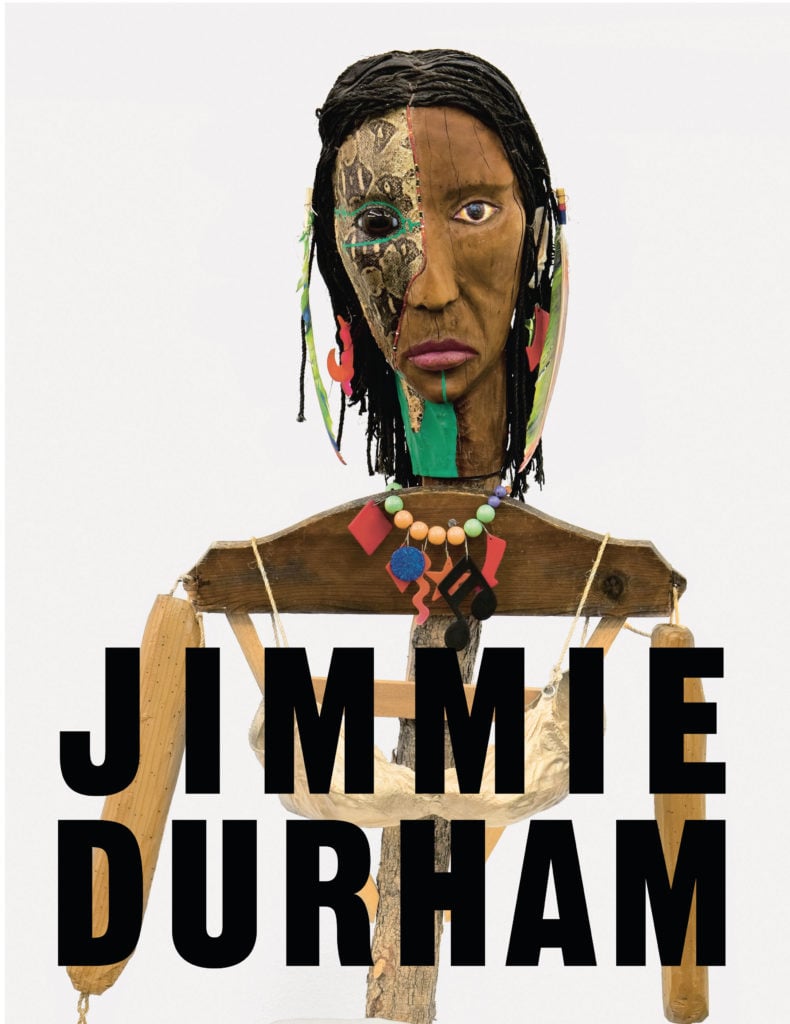

Catalogue for Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World (2017). Courtesy of Prestel Books.

Ultimately, Anne Ellegood has done Native art communities a favor by digging in and forcing this public discussion through her exhibition catalogue and her persistent framing of Durham as an American Indian. The catalogue showed that Durham still claimed to be Cherokee and still used our culture in his art and writing. Native people told Ellegood that Durham wasn’t Cherokee or Native for years, but she dismissed them and dismissed the tribes’ sovereign rights to define their own membership criteria. By doing so, she made apparent that this conversation could no longer be postponed.

No one by the surname of Durham was born in either of the two counties in Arkansas that the artist claimed as his birthplace. Kathy Griffin White (Cherokee Nation) confirmed that Jimmie Bob Durham was actually born in Harris, Texas, on July 10, 1940. From there, his family tree is easy to trace and yields no Cherokee ancestors.

American artist Jimmie Durham (left), inspects a car which was crushed with a six ton granite boulder painted with a human face in front of a large crowd at the Sydney Opera House, 05 June 2004, as a work which forms part of the Biennale of Sydney. Photo: Greg Wood/AFP/Getty Images.

Numerous non-Native people have tried to say, “Indigenous identity is complex,” as if that ends the conversation. It’s complex, but not incomprehensible. There are non-enrolled descendants of many tribal communities who still engage with and contribute to those communities. That is not Durham’s case. He is not a member of any of the three Cherokee tribes—the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the United Keetowah Band of Cherokee Indians, and the Cherokee Nation. The tribes, not the federal government, decide who is eligible to be a member. Under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, any of them can designate anyone they want as a tribal artisan. None has chosen to designate Durham to represent them in the art world.

Durham has no Cherokee ancestors, does not live in a Cherokee community, does not belong to a Cherokee ceremonial ground, and has not married into a Cherokee family. The situation could not be clearer. Yes, Jimmie Durham was part of the American Indian Movement, but so was Marlon Brando.

Thousands of non-Native people claim to be Cherokee. No one is in an uproar about Leon Polk Smith or Robert Rauschenberg claiming to be Cherokee, because neither launched their career as a Native artist. Neither positioned himself as the spokesperson for all American Indian people.

When you are less than two percent of your nation-state’s population and the public discourse about your people is dominated by stereotypes and misinformation, self-representation is profoundly important. Durham’s misrepresentation of Cherokee language, culture, and history is wildly off the mark. Curators and art historians should have reached out to the tribes, to Cherokee language programs, and to tribal museums.

Durham draws from a perplexing mishmash of various Native groups’ cultural practices. For instance, he claims that Trickster Coyote, who is significant to the Great Basin, Plateau, and California tribes, was Cherokee and played a role in our creation story. In the Southeast, however, Trickster Rabbit is a beloved cultural figure and did not create humans.

No one I know of is saying Durham does not deserve a retrospective, nor is anyone calling for censorship. His act of falsely claiming to be Cherokee is part of his narrative, as European-American artist Yeffe Kimball’s false claim of being Osage is part of her history.

The Walker Art Center has been receptive to the local Native community and is actively working to improve the situation. It will be fascinating to see how the Whitney and Remai Modern address Durham’s biography. If they continue his (bizarre) false claim of being born in Arkansas, they have failed to address the situation honestly.

Bert Benally’s installation Pull of the Moon, part of Navajo TIME 2014.

Photo: Robert Schwan.

Native American artists can and do speak for ourselves, and more are doing so in an international art arena. With so many powerful voices potentially to be shared, perhaps mainstream institutions could seek Native artists grounded within their communities, as opposed to those who barely touch the periphery. Ai Weiwei collaborated with Navajo artist Bert Benally on Navajo land, working with the Navajo Nation Museum. Tribal museums are an incredible resource for researchers and curators. Their mission includes educating the public; they are happy to share their considerable knowledge.

Non-Native people interested in learning about promising Native artists might research the artists that Native curators have chosen to work with, and even ask us directly why we choose to work with a particular artist. In the strong desire to overcome the burden of misinformation about Native peoples, most of us are very open to sharing information and insights.

Native communities can speak for ourselves. Give us the chance.

America Meredith (Cherokee Nation) is a visual artist, an independent curator, and the publishing editor of First American Art Magazine, based in Norman, Oklahoma.