Opinion

Where In the World Is ‘Salvator Mundi’? Kenny Schachter Reveals the Location of the Lost $450 Million Leonardo

Whether it's a 100 percent pure Leonardo da Vinci is another story, our columnist writes.

Whether it's a 100 percent pure Leonardo da Vinci is another story, our columnist writes.

Kenny Schachter

It’s a miracle!

When I received intel from a source with deep Middle Eastern ties as to the possible whereabouts of Salvator Mundi, the world’s most expensive, missing-in-action painting, I immediately went to the authority every writer consults first (whether they admit it or not): Wikipedia. In its entry, the work was referred to as being authored “by the studio of Leonardo da Vinci.” Today, when I returned to capture the precise language employed by the people’s encyclopedia, it had since—over the past week—been mysteriously altered to “a painting by Italian Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci dated to c. 1500. Long thought to be a copy of a lost original veiled with overpainting, it was rediscovered, restored, and included in a major Leonardo exhibition at the National Gallery, London, in 2011–2012.”

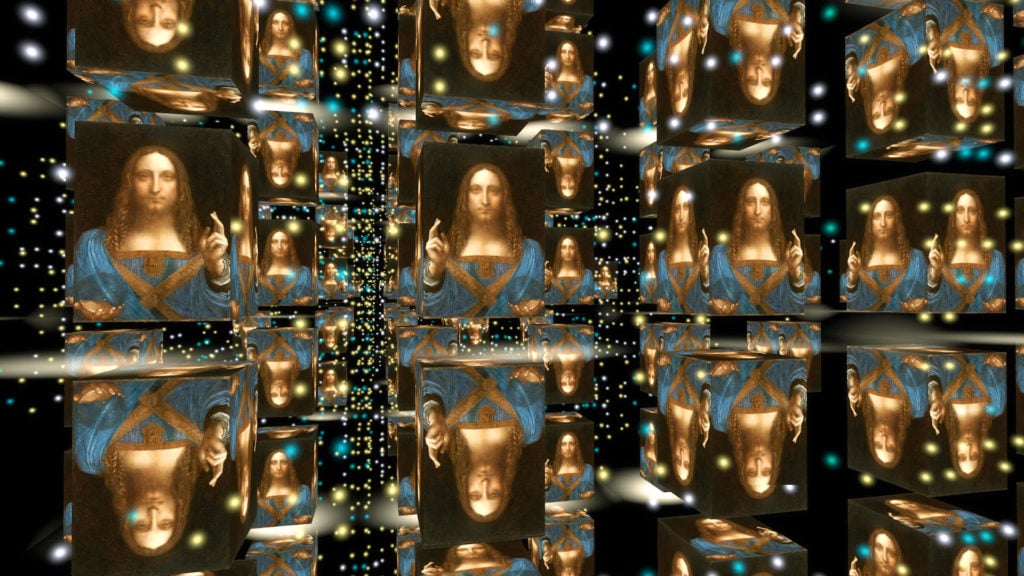

A new book on the subject, The Last Leonardo by Ben Lewis, concluded that the work was indeed more than likely painted by Leonardo’s studio, then possibly touched up by the master before it was brought to market—the marketplace being something he was very attuned to, by the way. On the evening of the painting’s Christie’s sale, auctioneer Jussi Pylkkanen confidently proclaimed that the painting was “previously in the collections of three kings of England”—a fact convincingly disputed by Lewis in his well-researched book—before hammering it down at the cartoonish (many would say foolish) sum of $450 million, with fees, to Saudi Arabia’s Prince Bader bin Abdullah bin Mohammed bin Farhan al-Saud, understood to have been an intermediary for his kingdom’s supreme ruler, Mohammad Bin Salman. That the last bid jumped from $370 million to $400 million is indicative of just how amateurish and unorthodox the process was that characterized this entire enterprise.

Ben Lewis’s new book The Last Leonardo. Cover courtesy of Random House.

Then, as we all know, the painting was allegedly gifted (how come I never get such generous presents?) by MBS to his pal Prince Mohammed bin Zayed of Abu Dhabi, crowned as the most powerful Arab ruler in a recent New York Times profile, to be displayed in his local Louvre branch as well as pledged as a loan to Paris’s actual Louvre for the upcoming exhibit marking 500 years since Leonardo’s death. (He died in France.) Then, in an unprecedented stunner, the painting was pulled from both and went on the lam, not to be seen since—though plenty has been heard on the subject.

On May 26, the Telegraph published an article to the effect that the Louvre insisted on attributing Salvator Mundi as “from the workshop of Leonardo da Vinci,” which may have accounted for MBS’s refusal to lend the work since such a reputational downgrade would diminish the value substantially. More damning to the painting’s authenticity as an autograph Leonardo was a Guardian article on June 2 that quoted the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Carmen Bambach saying she was wrongly referenced in Christie’s catalogue as attributing the painting to the artist alone. To the contrary, Bambach stated that the work was mostly painted by “Leonardo’s assistant, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio.”

Leondaro da Vinci, Salvator Mundi, ca. 1500. Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

Bambach said she had been contacted by London’s National Gallery last month to ask if it could cite her as a supporter of Salvator Mundi‘s authenticity—which, seven years after the museum’s Leonardo blockbuster, is a peculiar move at the least, considering this late stage of events. Could the National Gallery be trying to cover its tracks after making the unprecedented move of installing the work in its exhibition—and thereby conferring the National’s imprimatur—without definitive proof the work was by Leonardo?

The London museum’s quandary shows the pitfalls of putting box-office interests above institutional ethics and standard professional practices in the name of blockbuster mongering. They’d make a nice defendant in any lawsuit if MBS seeks a refund in whole or part from Christie’s et. al. In fact, Legal proceedings are still underway as to exact extent of Sotheby’s role in the painting’s private-treaty sale between advisor Yves Bouvier and its previous owner, Dmitry Rybolovlev.

So the question remains, how do you lose a $450 million newly discovered Leonardo? In the murky Middle Eastern waters nothing is quite crystal clear, but my sources—including two principals involved in the transaction who claimed the work has been unequivocally paid for (though I’ve heard more than a few musings it has been only partially settled)—disclosed more. You won’t believe where I’m told the painting is today. Apparently, the work was whisked away in the middle of the night on MBS’s plane and relocated to his yacht, the Serene.

The Serene. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A little backstory on that yacht: originally built in 2011 for the Russian vodka tycoon Yuri Shefler and then rented to Bill Gates for $5 million per week, it came into MBS’s possession after he caught a glimpse of the ship one day and had his flunkies go knocking (by dinghy one would assume) with an offer of approximately €500 million, which the Russian couldn’t refuse. (Thanks again, Wikipedia). There’s a nice symmetry there with the “value” of the painting, which my sources say will remain onboard until MBS finishes transforming the ancient Saudi precinct of Al-Ula into a vast cultural hub—basically an art Disneyland—that will no doubt compete with Abu Dhabi’s Louvre and, more significantly, the Jean Nouvel-designed National Museum in Qatar, the sworn enemy of the Saudi crown prince.

After the painting was initially found in shards—it had split into five discrete pieces and had to be reattached during restoration, per Lewis’s book—and its surface literally shaved before being nearly fully restored and repainted, what harm could the occasional splash of seawater do?

Meanwhile, there are other telltale signs of Saudi Arabia’s impending push into the world of art and entertainment. For one, they recently bought some Kusama mirror rooms—the must-have accessory for any private museum worth its weight (in oil)—from a friend, and have been picking up George Condos, Richard Princes, and Richard Serras too. To add to their penchant for all things bling, the Saudi regime has made a sizable investment into the back catalogue of bronzes still in the inventory of goldsmith-turned-sculptor Arnaldo Pomodoro (who turns 93 this month). I’m told they have even made queries about bringing an iteration of the Frieze Art Fair to the Kingdom. (With an average summer temperature of 113 degrees Fahrenheit in Saudi Arabia, the fair might feel right at home.)

The headlong shopping spree for international cultural capital—and global-tourism fodder—that is currently taking place across the region has spurred an art arms race, with munitions consisting of obvious art by obvious market darlings. Qatar was said to have spent $1 billion per year on Western art over an extended period, so the Saudis have a lot of catching up to do. (If you lined up all the Serras being air-lifted to the Arabian desert, it would probably outdo Trump’s dreamed-of border wall.)

But a word to the advisors of MBS, like Sotheby’s Allan Schwartzman, who is presently serving on the advisory board of the Royal Commission for Al-Ula: you better advise wisely, or you might end up a 21st-century version of Judith and Holofernes.