Have you ever wondered what your rights are as an artist? There’s no clear-cut textbook to consult—but we’re here to help. Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, is answering questions of all sorts about what kind of control artists have—and don’t have—over their work.

Do you have a query of your own? Email [email protected] and it may get answered in an upcoming article.

Page Six says that Khloé Kardashian has been suing people to take down unflattering photos of herself. (They’re not even that unflattering, they’re just not as flattering as they could be.) People put up unflattering photos of me all the time. Can I do what Khloé did?

We get a lot of variations on this question, and it’s understandable. Most good nights out are followed by a hungover morning spent de-tagging photos. Wouldn’t it be nice to send a cease and desist to that one frenemy whose photos of you always end up being 70 percent neck?

You might assume that Khloé and her team have discovered a dynamic new legal strategy—I mean, look at what her dad did for O.J.—but in reality, this story just demonstrates yet again the power of copyright.

The photo in question was actually taken by an employee of the Kardashian business and posted accidentally. “Khloé looks beautiful but it is within the right of the copyright owner to want an image not intended to be published taken down,” Tracy Romulus, chief marketing officer for KKW Brands, said in a statement.

But in addition to being, well, a little obsequious, this language implies that Khloé is the copyright owner, when we know that copyright normally rests with the photographer. If I had to guess, I would assume that the photographer who took the photo has a work-for-hire contract with the Kardashian family, in which case the copyright does in fact belong to them.

(Why is the New York Post able to host this photo when Instagram is not? Because almost all journalism falls under the category of fair use.)

In other words, in absence of a formal work-for-hire contract, yes, your friend has a copyright claim on your jowls. Happy de-tagging.

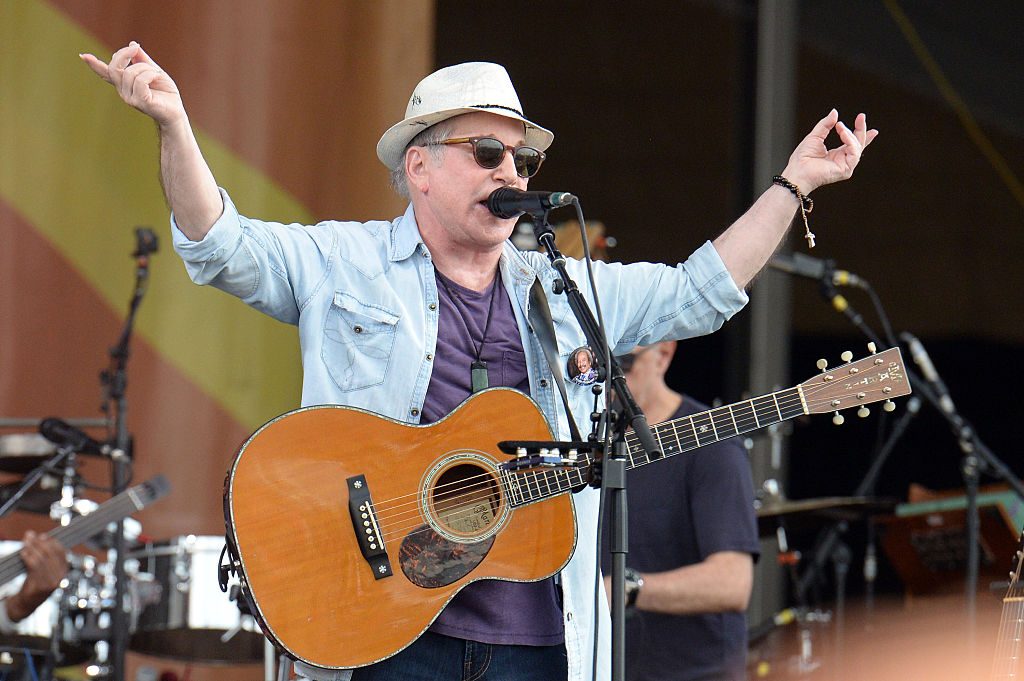

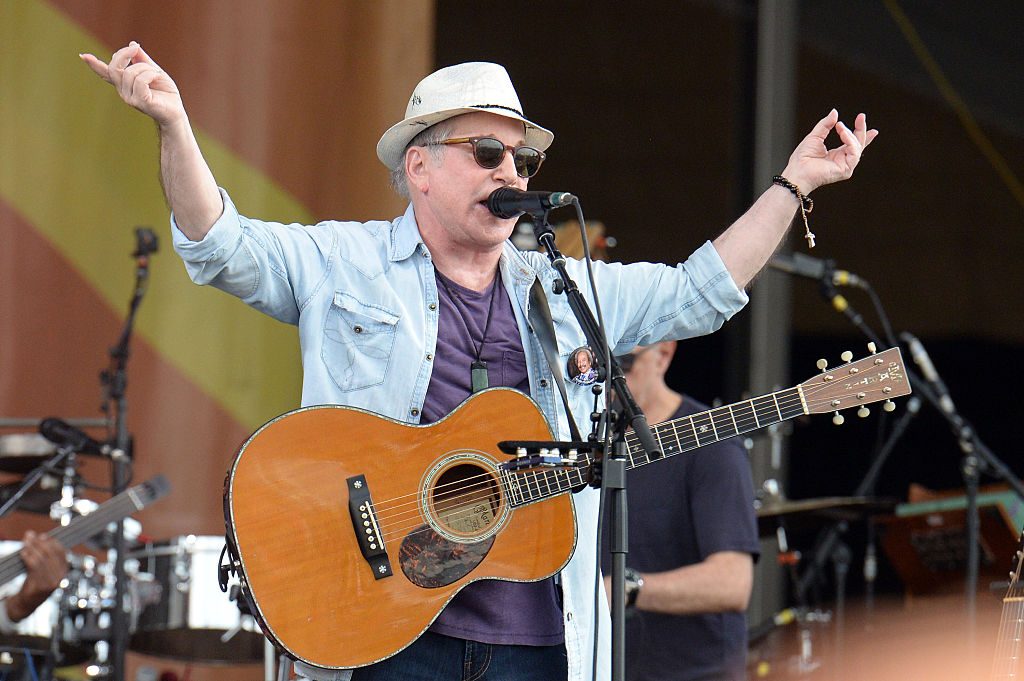

Singer Paul Simon performs at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival on April 29, 2016 in New Orleans, Louisiana. (Photo by Scott Dudelson/WireImage)

Paul Simon is the latest musician to sell his entire song catalogue for a tidy sum. Do you foresee a way for fine artists to cash in on this development—someday, somehow?

It’s true: Superstar musicians like Neil Young, Bob Dylan and Taylor Swift have all been cashing out in what can only be seen as a victory for copyright enthusiasts. Unlike Michael Jackson’s 1985 purchase of the Beatles catalogue, which seemed to be based in admiration but was done behind the back of his then-friend Paul McCartney, these new buyers tend to be financial entities motivated by nothing more than the value they assign to intellectual property.

Why is this all happening now? I have my theories. It seems that collective rights organizations for musicians have been cracking down on YouTubers and Twitch streamers, which we’ve covered in this column before, as part of a broader campaign to make licensing music for internet videos just as expensive as it is for film and television. As the need for music proliferates, so do the songs’ value.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to imagine a parallel scenario for visual artists. Musicians make money off of both performing their songs and receiving royalties from recordings. Once a painting is sold, however, copyright is all the artist has left (one of many reasons why it’s a terrible idea to sell your copyright). Much as I hate to place further weight on this bandwagon, I’m inclined to say that NFTs might actually be useful for visual artists here… Wait, don’t go!

What excites me about NFTs is the potential for giving increased agency to the original creator. Since you can attach riders to the blockchain contract (including for a resale royalty), artists might finally be able to retain some control over their work, even after it has been sold.

But, alas, until Twitch streamers start putting Picassos in their backgrounds, I don’t see artists making the same kind of bank from licensing their oeuvre as musicians do.

Marina Abramović, The Artist is Present (2010). Courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery.

I’m planning on staging a piece of performance art on Zoom. Do I have to get likeness rights signatures from all of the audience members or any other kind of permission?

The problem with performance art—besides the fact that it’s difficult to copyright—is that everyone usually leaves within the first three hours. Rude! Staging your performance on Zoom feels like a great way to allow people to drop in and out without having to make an awkward exit.

Now for the copyright bit. Once the performance is fixed in tangible form, i.e. recorded, it is officially copyrighted and becomes an asset that you can sell (though maybe not for as much as you would like; even Marina Abramović is probably not as wealthy as you think she is).

Thankfully, the process of obtaining permission from audience members need not be onerous. Zoom has a recording disclaimer function built in, but I would suggest including a brief note in your email invitation as well. Just let viewers know that the whole thing is being recorded and may someday be displayed publicly, or perhaps even broadcast. You can also ask them to sign a simple release.

Chances are they will agree with no fuss and look forward to one day passing a monitor in a gallery and catching a glimpse of themselves in your recording. Break a leg!

Warhol’s image over Lynn Goldsmith’s 1981 photograph of Prince. Courtesy of Lynn Goldsmith.

Why did that judge rule against the Warhol Foundation in that copyright lawsuit involving the portrait of Prince? I can’t say I understand it.

Many people are having trouble understanding it. The Warhol Foundation is appealing, and while I have not discussed the case with anyone there, in the interest of full disclosure I should say they are a client of ARS.

The case concerns a photograph of the Purple One taken by celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith for Newsweek magazine in 1981. In 1984, Vanity Fair commissioned Andy Warhol to make an illustration from one of the photographs, which it had licensed; Warhol went on to make 16 paintings based on the photo. Though a 2019 ruling found the works to be fair use, last month judge Gerard E. Lynch stated that the “Prince Series” “retains the essential elements of the Goldsmith Photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements,” and ruled in Goldsmith’s favor on appeal.

In his own public head-scratching about this ruling, Warhol biographer Blake Gopnik reminds us in the New York Times that Duchamp didn’t do anything to that urinal when he turned it into Fountain. It is the context that made it into art, which should have been enough for the Prince work. But fair use is a tricky thing, and one of the elements that goes into determining it is the degree to which the new work hurts the market for the original. I think Warhol’s treatment of Goldsmith’s photo, if anything, enhances its value.

In essence, I can’t really help you understand Judge Lynch’s thinking, because it doesn’t make sense to me either. We’ll be watching the appeal with great interest.