Have you ever wondered what your rights are as an artist? There’s no clear-cut textbook to consult—but we’re here to help. Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, is answering questions of all sorts about what kind of control artists have—and don’t have—over their work.

Do you have a query of your own? Email [email protected] and it may get answered in an upcoming article.

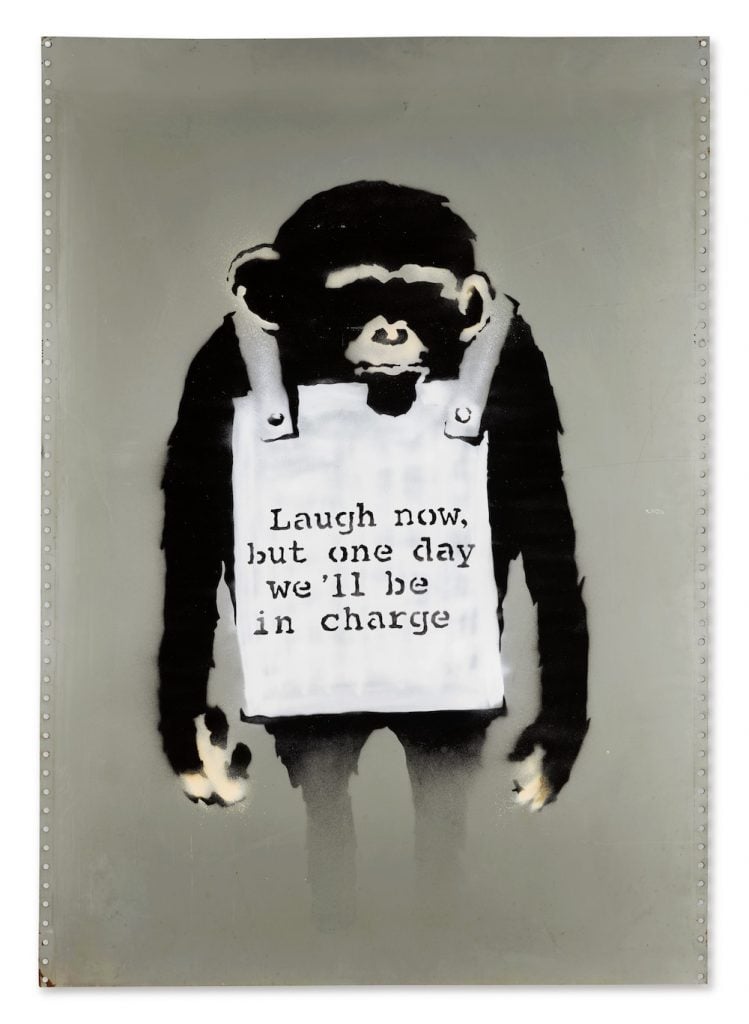

I own an original Banksy print—it’s one of an edition of 600. Can I turn it into an NFT?

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but even if you owned all 600 editions, the copyright on this work would, as ever, rest with its creator, whomever he may be…

It’s undeniable that NFTs purchasers seem to value a certain street-art, punk aesthetic, so Banksy is in demand. (He already has an NFT-minting imitator called Pest Supply, a play on Pest Control, the real Banksy’s authentication service. Pest Supply claims “to be working in the vein of Elaine Sturtevant,” according to The Art Newspaper.)

Perhaps not surprisingly, we have been receiving a lot of NFT queries in this column lately. The difficulty is that the rules that govern NFTs are a lot less defined than those that govern copyright in the tangible world. It’s a bit like people asking about how SEC regulations apply to cryptocurrency: for the time being, they really don’t, and that’s probably part of the appeal. The craze is also slightly reminiscent of the early days of Napster, the music-sharing platform of the early aughts that preached free tunes for all. Sounds nice, but what about the creators? As the platform gained popularity, so did the backlash from music’s copyright holders, who successfully shut down the operation.

We are already starting to see some cracks in this free-for-all mentality that the nascent world of NFTs shares with those early days of music streaming. Recently, Jay-Z sued Damon Dash to stop his attempt to sell Reasonable Doubt as an NFT. This promises to be a landmark case and one we will certainly follow.

To return to your question regarding whether or not you should make a Banksy NFT, the answer is: you probably can get away with it (you wouldn’t be the first!), but you also probably shouldn’t. Even though Pest Control, Bansky’s aforementioned authentication committee, has not yet taken any action to stop the sale of unauthenticated NFTs, they absolutely could do so in the future. Plus, Banksy has become more aggressive about seeking to enforce the copyright for his imagery. He may be a rebel, but we thought the same thing about the members of Metallica, and they went ahead and sued Napster all the same.

So I suppose you’ll just have to use your Banksy print for its original purpose: impressing the coolest people in the world.

A police officer in Hopkins, Minnesota. (Photo by David Joles/Star Tribune via Getty Images)

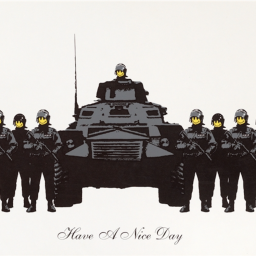

Is it really true that police officers are playing Top 40 hits when being recorded with video phones? Would this really prevent the videos from being uploaded?

It’s true and very unfortunate. The purpose of copyright is to protect artists and amplify voices, not stifle them.

As the number of Americans who film, on principle, any encounter they see between civilians and police has grown in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, officers, in turn, have taken to playing Taylor Swift, the Beatles, and even Sublime’s “Santeria” during these encounters.

This month, we finally got confirmation that this is an evasion tactic when an officer in Oakland, California, told the person filming him as “Blank Space” blared from a phone in his shirt: “You can record all you want, I just know it can’t be posted on YouTube.”

While in his case, the tactic didn’t work—you can, in fact, watch that back and forth on YouTube—the officer seems aware of the ongoing DMCA takedown campaign that we’ve previously addressed in this column (and is seeking to use it to his advantage).

It’s becoming increasingly difficult for YouTubers and Twitch streamers to use copyrighted music in the background of their videos. The broader implications of this crackdown, which is driven by the simple fact that these platforms are growing faster than they ever have thanks to the pandemic, remain unclear.

I don’t criticize the groups behind this current DMCA push, since they do for musical artists what ARS does for visual artists, though I will say that the policeman’s behavior implies that he and his colleagues think there’s some automated system taking down any video that features popular music. But shades of grey are necessary when it comes to copyright protection.

YouTube does have a Content ID system that automatically flags potentially copyrighted material, but humans enter the process eventually. Clearly, the people behind the current DMCA campaign need to do a better job of explaining how and why they are removing content so it is not instrumentalized for a very different aim.

Artist Derrick Adams auctions an NFT titled Heir to the Throne, commissioned by musician Jay-Z to celebrate the 25th anniversary of his debut album “Reasonable Doubt” at Sotheby’s on June 29, 2021. (Photo by Noam Galai/Getty Images)

I’m a photographer who takes the odd red carpet and magazine assignment to pay my rent. I saw that Jay-Z sued the photographer who took the iconic photo on the cover of “Reasonable Doubt.” Is this something that I need to worry about?

Mr. Knowles-Carter seems to be a bit lawsuit-happy at the moment, doesn’t he? Just see the answer to this month’s NFT question. And it all seems to involve his litigiously named debut album. Whatever is going on here is unorthodox.

In his complaint, Jay-Z claims that photographer Jonathan Mannion has been “misusing his likeness on merchandise including photo prints, shirts, and turntable mats, and licensing his image to others without permission,” supposedly “on the arrogant assumption that because he took those photographs, he can do with them as he pleases.”

New litigation surrounding a 1996 debut album is strange, but another odd factor here is that Jay-Z is suing Mannion in California on publicity rights. As previously addressed, publicity rights (a.k.a likeness or personality rights) operate a little like copyright, but it’s odd that either would be asserted by a musical artist, since contracts before the photo shoot for an album usually make it clear that the resulting image will be owned in its entirety by the label.

None of this is relevant for any of the work you’re doing, because your work is journalistic rather than commercial, and therefore thoroughly protected when it comes to both copyright and publicity rights. That said, if you find yourself in the position to shoot Jay-Z in the Hamptons this summer, you may want to keep your distance.

This seems like the kind of spot where you could stream anything as an art piece, right? (Photo by Frédéric Soltan/Corbis via Getty Images)

I’m thinking of doing an “art piece” where I stream the Olympics for free at my bar, sans subscription, a.k.a piracy. Do you think I might be able to get away with this? It’s a very artistic bar. It’s in Bed Stuy.

While I admire your dedication to subterfuge, I must begin by pointing out that every event in the Olympics is streaming for free, with ads, on NBC’s Peacock app.

But you raise an interesting question, because it is true that you can’t just show whatever you like, however you like, in your bar. This should not come as surprise to anyone who has stuck around in one long enough to see the end of a baseball game, and that small print that reminds you that “this telecast is copyrighted and any rebroadcast, retransmissions, pictures, descriptions, or accounts of this game without the express written permission of Major League Baseball are prohibited.”

This essentially means that it would be illegal to broadcast the game in a movie theater and charge tickets, because you’d be making money off the MLB’s property. Yet, in a way, isn’t this what sports bars are doing, but just charging for beers instead of tickets? And what if you wanted to stream the new season of Succession, should your Bed Stuy denizens tolerate such displays of wealth and excess?

Bars are protected by a loophole in the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act that protected Disney’s ownership of Mickey Mouse, among other properties. As a concession to layfolk, it included a “homestyle exemption” that also applies to music and says that your bar can use music or television equipment “of a type that is commonly used in one’s home.”

Naturally, the standard at-home equipment has changed since 1998, but the law is weirdly specific here: your bar must contain less than 3,750 square feet of space, your televisions may be no larger than 55 inches, and at any point, no more than four screens may show any given broadcast. Since then, it would seem that the copyright holders have become a little more lax, but not without exception. In 2012, one Texas bar was hit with a $32,000 fine for showing a single UFC match without a license—so keep that in mind if you’re planning on streaming something that’s rare or expensive.

The Olympics should be completely safe, since NBC seems to want to have them reach as many people as possible. And for the record, art is nowhere near as protected as parody and satire, so you’d be much safer showing something copyrighted as a “bit,” in the future. Perhaps a so-bad-it’s-good classic like Cruel Intentions? Something tells me that your Bed Stuy barflies are comfortable with irony.