Looking for a blockbuster piece of art investment advice? Here’s one: “It is more profitable to invest in the artworks of more narcissistic artists.”

That a line from a new paper in the European Journal of Finance by Yi Zhou, a Florida State University professor who studies empirical asset pricing.

“You know, my data does support that: Narcissistic artists will have higher prices and they will have more recognition in the art world,” Zhou told me earlier today in a phone interview. “If I had a large pool of money, I am pretty confident that this result holds strongly.”

Maybe it’s no surprise that art actually rewards the self-absorbed. But how to prove it?

Zhou’s answer: Measure their signatures.

Evidently, in psychology, signature size is closely linked to self-regard, and there happens to be plenty of accessible data on artists’ signatures. Zhou measured hundreds of signatures, then compared the results to historical auction price data, numbers of museum shows, and “artistic reputation” (as ranked by a crack team of FSU graduate students).

The conclusion is that artists with bigger-than-average signatures—and, it is implied, bigger egos—get greater-than-average attention. You can take this to the bank, Zhou’s paper argues: “A one standard deviation increase in narcissism increases the market price by 16% and both the highest and lowest auction-house estimates by about 19%.”

Li Zhou’s equation for how narcissism affects the art market

Attempting to confirm her hypothesis, Zhou also looked at “two alternative proxies for narcissism:” number of self-portraits and frequency of uses of the word “I” in published interviews. Both measures also showed statistical correlation with success.

“A one standard deviation increase of self-portraits… increases the market price of art by 13%,” the paper argues. “A one standard deviation increase in First-Person Pronouns… will increase market price of art by 4%.”

Strangely, the narcissism premium seems to decrease for contemporary (meaning, here, post-war) artists, as opposed to modern artists. “In two subsamples for modern and contemporary artists, respectively, a one standard deviation increase in narcissism increases the market price of art by about 25% for modern artists and by about 13% for contemporary artists,” the paper concludes.

“It would be a very good research topic to try to find out why this is the case,” Zhou said via phone.

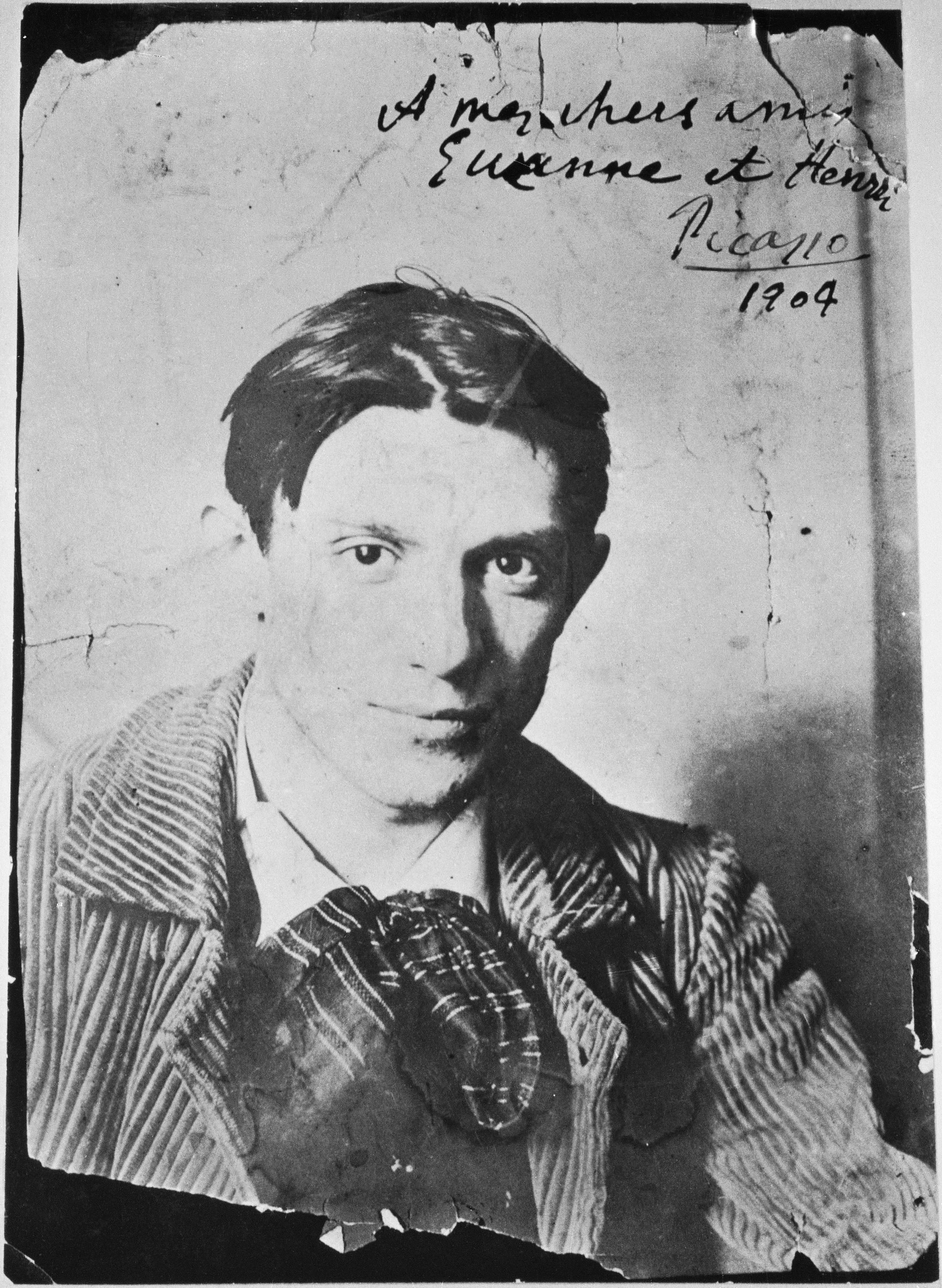

Signature of Pablo Picasso. Public domain, scan by Hubertl.

Sophistry, you say? Is this one for the blog of Spurious Correlations?

On the science, I cannot comment. But after all, it would not be particularly outrageous to argue that artists who have grandiose self-images are better at convincing others that they are geniuses.

Zhou cites one definition of clinical Narcissistic Personality Disorder: “an exaggerated sense of entitlement, exploitative tendencies, empathy deficits, and a need for excessive admiration.” Sounds like behavior that is rewarded in the art world to me!

A final takeaway: Professor Zhou’s method of signature analysis is inspired by research in the field of corporate finance. There, economists have studied how CEO narcissism affects company performance by studying signature size on corporate documents.

In that research, CEO narcissism “predicts overinvestment, less innovation and lower profit.” But take heart, self-involved corporate titans: “Despite this negative performance, narcissistic CEOs enjoy higher compensation.”

Zhou essentially argues that the same selfish characteristics that can harm a company can actually secure long-term artistic reputations. Basically, the art world may be the place where self-obsession and delusions of grandeur are put to some sort of social use. Better to quarantine them in the studio than have to deal with them in the boardroom.

In sum, you do not want your CEOs thinking of themselves as artists. Maybe we can all sign off on that?