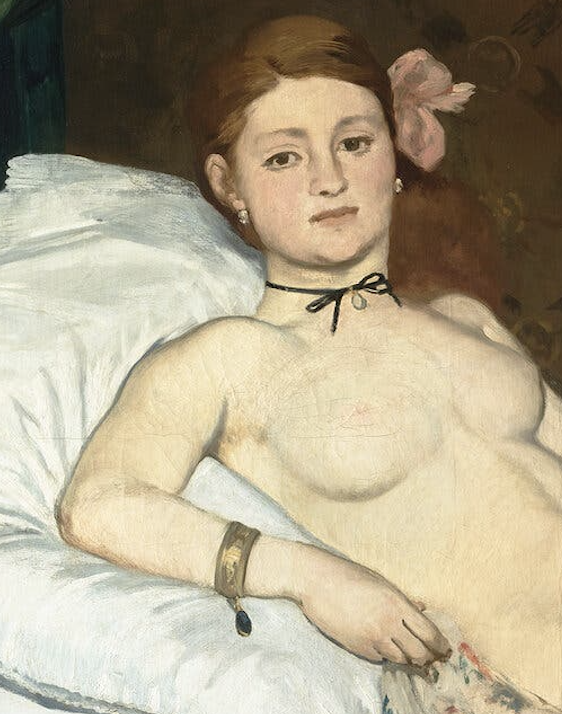

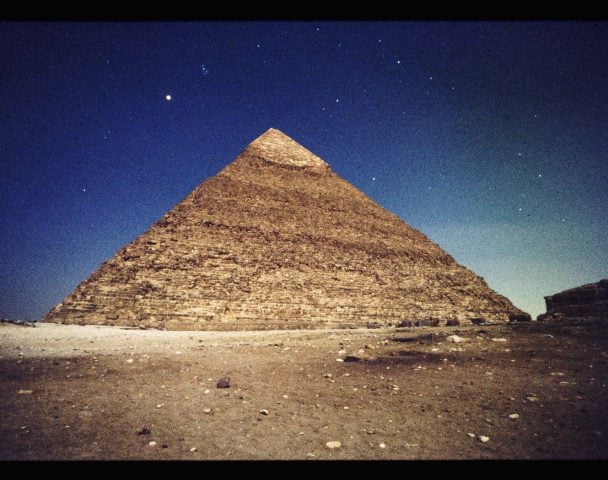

Olympia stares out from the canvas, her level gaze almost a dare.

In Édouard Manet’s famed 1863 painting, a woman—a courtesan, in fact—reclines on a chaise lounge. She is naked and her body is pale, almost muscular, her legs short and knobby. Beneath her, white sheets are rumpled haphazardly. Pale blue and white silk slippers dangle scandalously from her sullied feet. An orchid is pinned above her ear, into her red hair, a winking reference to sex.

She wears only jewelry, a pair of pearl earrings and a gold band on her wrists. Such adornments, in 19th-century France, would have offered clues hinting at her profession—but none quite so explicit as the title itself, Olympia, a common name for prostitutes of the era.

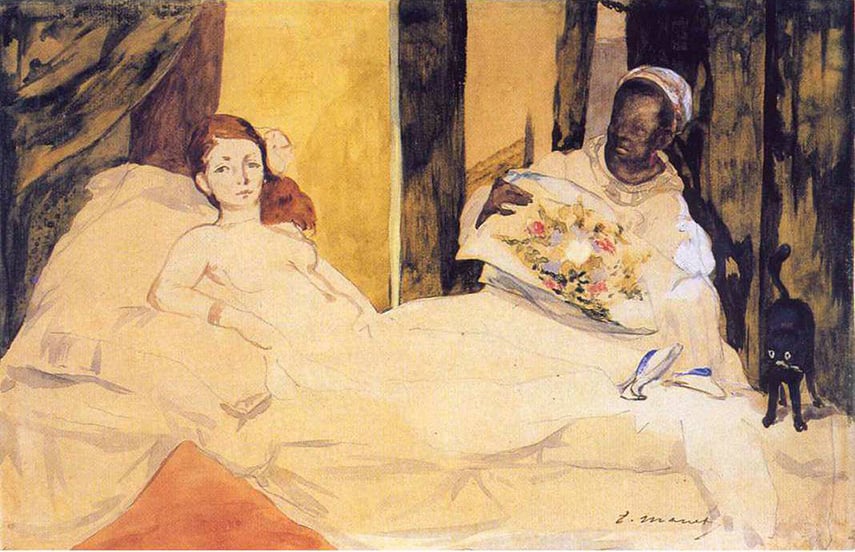

Behind the titular figure, we see a maid, a Black woman fully dressed in contemporary clothing. She approaches the courtesan with a floral bouquet, perhaps a gift from a client. Olympia pays no mind. She stares out of the canvas, toward us, the viewers, with a look of inscrutable confidence. She seems to ask, “Do you like what you see? Are you ready to pay?”

Detail of Olympia (1863) by Édouard Manet.

Manet’s consummately modern image debuted at the Salon of 1865, eliciting a torrent of public and critical outrage, mockery, and even violence. At the Salon, incensed viewers attempted to lance the canvas with their umbrellas. The painting had to be rehung, in a far, high corner, out of reach—as the journalist Antonin Proust recalled, “If the canvas of the Olympia was not destroyed, it is only because of the precautions that were taken by the administration.”

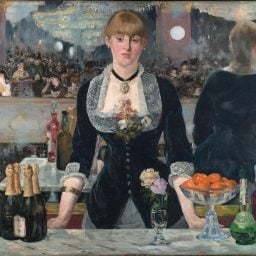

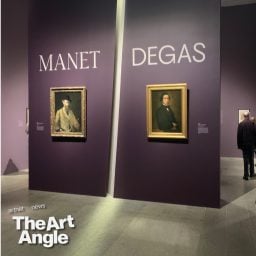

Today, the painting is regarded as a masterpiece of the modern era, an image bristling with 19th-century realist energy. Olympia is the star attraction at the Musee d’Orsay in Paris, where it has been part of the collection since 1986 (the painting has belonged to the French State since 1890. Prior, it was in the collection of the Louvre, and before that the Musée Luxembourg). Now, Olympia—160 years after its creation—is on view in New York for the first time in the long-awaited exhibition “Manet/Degas” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This is the first time the Olympia has been shown in the U.S. and only the third time it has left France.

Titian, Venus of Urbino (1538). Collection of the Uffizi.

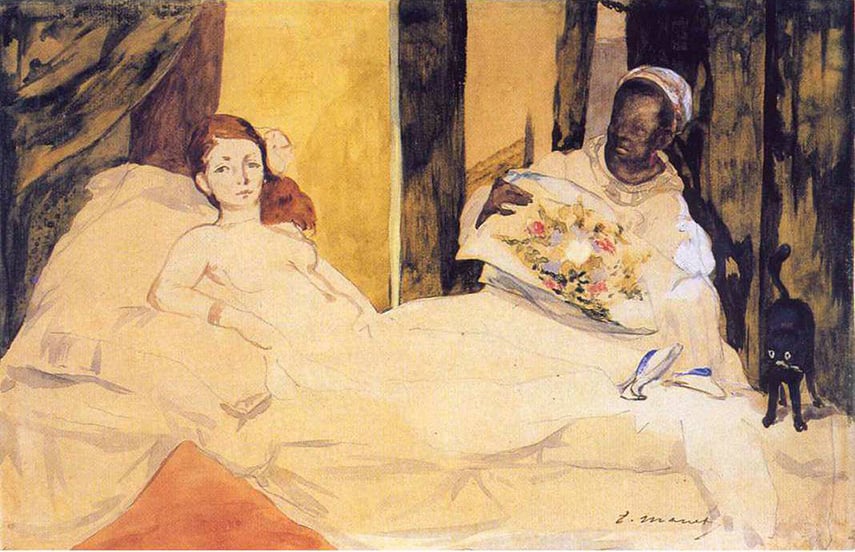

Compositionally, Olympia pulls from the ancient traditions of the reclining female nude, as well as depictions of the goddess Venus dating back to Roman times. Manet’s most direct reference was Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1534). Titian’s sensuous scene is an undoubtedly erotic painting and it has even been suggested that the work is a disguised portrait of a well-known Florentine courtesan. Yet Titian’s Venus remains a scene removed from reality and idealized.

Olympia, on the other hand, puts sex and commerce front and center. Here Olympia sits up, not coquettishly but frankly. Her face is the imperfect face of a real woman, her lips a bit thin, her profile slightly asymmetrical. She reclines—not in a palace of unimaginable ostentation, but in the closed room of a Parisian apartment. With her hand over her mons pubis, she does not invite, but guards herself, seemingly in demand of payment. It is a painting that offers no easy answers to the viewer.

On the very special occasion of the painting’s New York debut, we’ve taken a closer look at Manet’s Olympia and found three facts that might make you see it in a new way.

1) The Real-Life Women Behind ‘Olympia’ Are As Fascinating As the Painting

Édouard Manet, La négresse (Portrait of Laure) (1863). Collection of the Pinacoteca Giovanni e Marella Agnelli, Turin.

Those familiar with Manet’s oeuvre may recognize the two women in Olympia; the artist used both women as models on several occasions. The maid was modeled by a woman named Laure. Believed to be of Caribbean or possibly African heritage, Laure’s last name is not known, but her address is. One of Manet’s notebooks noted, “Laure très belle négresse 11 rue de Vintimille 3e” (the notebook was included in the exhibition “Le Modèle noir, de Géricault à Matisse” at the Musee d’Orsay in 2019).

Laure’s neighborhood was home to a small but visible Black population that was growing following the abolishment of slavery in France and its colonies in 1848. The neighborhood was home to many artists, poets, and writers; Manet lived only a short 10- or 15-minute walk from Laure’s address. While it’s unknown how the artist and model were introduced, Laure modeled for Manet for two other paintings in addition to Olympia: Children in the Tuileries Garden (1862) and Portrait of Laure (1862–1863).

Laure has become a subject of increased interest in recent decades, as historians reconsidered the presence of Black figures in Western art. In Lorraine O’Grady’s important essay, “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity,” she wrote, “Olympia’s maid, like all other ‘peripheral Negroes’, is a robot conveniently made to disappear into the background drapery. While the confrontational gaze of Olympia is often referenced as the pinnacle of defiance toward patriarchy, the oppositional gaze of Olympia’s maid is ignored; she is part of the background with little to no attention given to the critical role of her presence.”

Victorine Meurent, Self-Portrait (c. 1876). Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Olympia was modeled, meanwhile, by Victorine-Louise Meurent, who was nicknamed La Crevette (“the shrimp”) for her small stature and reddish hair. Meurent first worked for Manet in 1862, ultimately modeling for him a total of 9 times, including for Le Dejeuner Sur l’Herbe, where she is the basis for the nude female figure.

The notoriety of Manet’s painting would rub off on Meurent, earning her an uncommon fame, but also suspicion. While some male art historians and biographers dismissed Meurant as a tragic case, doomed to an early death, that was far from the truth. Indeed, the art historian Eunice Lipton discovered that Meurent lived to the age of 83.

Meurent traveled to the U.S. as part of an acting troupe in 1868, and upon her return would enroll in art classes at the Academie Julian. Born to a working-class family, Meurent had longed to be an artist—and she did become one. In 1876, she would even be included in the Salon, while Manet was rejected.

Only a handful of her own works are known to survive. These include Le Jour des Rameaux or Palm Sunday which was located in 2004 and now hangs in the Musée Municipal d’Art et d’Histoire de Colombes and Self Portrait, which is found in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

2) About That Cat…

Detail of Olympia (1863) by Édouard Manet.

A black cat, easy to miss at first glance, arches its back, standing at the foot of Olympia’s bed. The cat’s yellow eyes are full of alarm, but otherwise, the animal nearly disappears into the dark green curtains behind it, a phantom.

While Manet made many late compositional additions to Olympia, the cat is present in all his sketches, as an element that serves several functions. Firstly, it marks a deliberate change from Titian’s Venus of Urbino, where a dog, a symbol of fidelity, sleeps soundly at the goddess’s feet.

Detail of Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538).

Manet’s replacement of the dog by a black cat adds an uncanny element. Since Medieval times, black cats have held associations with magic, thievery, and evil. Animals inspired suspicion for their independence, and inability to be trained. In this way, the cat has been aligned with cultural prejudices against women, particularly independent women, and those who live unconventionally, much like Olympia herself.

Manet’s cat, with its wide yellow eyes, also indicates that someone has entered the room unexpectedly. In this way, the cat serves as another witness to the unfolding events. While the viewer is immediately caught in Olympia’s sight line, the cat’s hooded stare is unexpected, alarming, even voyeuristic.

3) Desire, Deception, and Disease

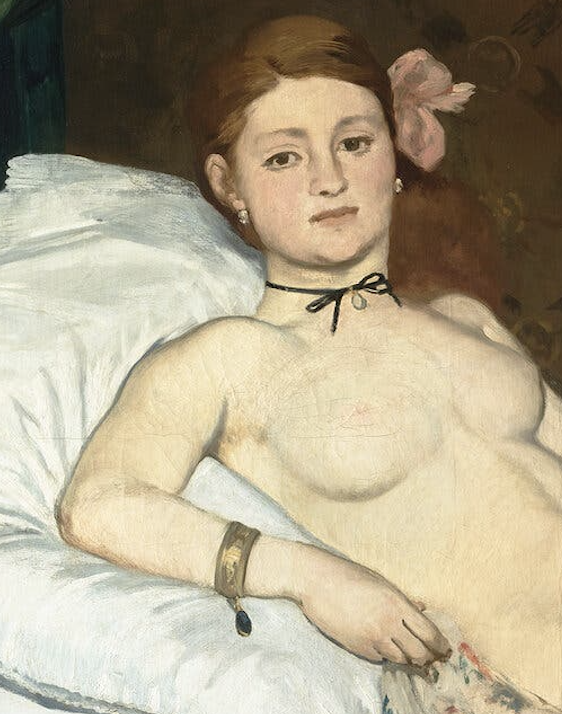

Edouard Manet, Study for Olympia (1863).

“The horror of the morgue” is how critic Victor de Jankovitz described Olympia when it debuted. “A painted corpse,” decried the influential writer-brothers Edmund and Jules de Goncourt. “Putrefied,” described another. Olympia’s pale white body, these critics noted, was barely modeled. The shadows Manet painted were not on her limbs and torso, as was commonly done, but around her hands and feet. The lines of her face gave Olympia an aged, even dirty appearance.

Those sickly descriptions, however, may have been astute. In her essay “Manet’s Olympia: If Looks Could Kill,” art historian Dolores Mitchell argues that Olympia functions as a Venusian memento mori, her imperfect form akin to a bruised fruit or wilting flower in a Dutch still life—a warning against earthly pleasure. She notes that the ribbon tied at Olympia’s neck gives her face a mask-like appearance; in 19th-century France, a woman with a mask was a common visual metaphor for courtesans with venereal disease.

Across 19th-century Europe, public health campaigners associated syphilis with prostitutes, as exemplified by such cartoons.

In Paris, in 1863, the year of Olympia’s creation, in fact, the syphilis epidemic had reached a crisis point, affecting the artist directly, as Manet’s father had died from the disease in 1862. The artist himself would die from a botched surgery relating to syphilis in 1883. At the dawning of the industrial age, a new class of bourgeois men were suddenly afforded the financial means, and the leisure time, to indulge in the pleasure of the brothel—but not without effect to public health.

Mitchell notes “Manet’s tendency to mythologize his life” by encoding tiny biographical clues in the paintings. Viewed through this lens, Olympia’s frank gaze had an even more troubling symbolism for its contemporaneous viewers. As murmurs of the disease swirled through the city, bourgeois men—the very clients who fueled the epidemic—were confronted in the Salon by a sickly courtesan while accompanied by their wives and children.

The art historian Therese Dolan notes in her essay “Fringe Benefits: Manet’s Olympia and Her Shawl” that Manet added a shawl to the composition in its late stages. A shawl was the defining gift of a corbeille, a wedding trousseau given by a husband to his new wife. The detail thereby added another allusion to marital betrayal to the picture.

Émile Zola, the literary father of Realism, summed up Olympia’s effect succinctly: “When our artists give us Venuses, they correct nature, they lie. Édouard Manet asked himself why lie, why not tell the truth; he introduced us to Olympia, this fille of our time, whom you meet on the sidewalks.”