For some art lovers, considering how the Museum of Modern Art’s latest architectural expansion will affect the art market is like asking how the back-to-school shopping surge will impact international sweat-shop labor: it’s uncomfortable and maybe a little offensive. Yet MoMA has been integral to the market arc of artists’ careers and legacies almost since its inception.

The museum’s founding in 1929 played a significant role in establishing New York as the epicenter of the American avant-garde. Its esteemed former chief curator of painting and sculpture, William Rubin, awarded Frank Stella not one but two MoMA retrospectives, making Stella the sole living artist to earn that distinction. And more recently, MoMA’s gamble on Marina Abramović’s surprise 2010 blockbuster, “The Artist Is Present,” proved that performance art can be not only viable, but even essential viewing for the public at large.

To pretend these choices, and countless others made by MoMA over the past 90 years, changed nothing about the commercial art world would require a level of innocence rarely seen outside a hospital nursery. It’s not only fair, then, but necessary to ask how the museum’s monumental new form will affect the market.

Any serious attempt at answering that question has to account for the building itself, remade at a cost of $450 million by Diller Scofidio + Renfro in conjunction with Gensler. But just as important as the architectural changes, if not even more so, are the accompanying curatorial shifts that will determine what fills new and old spaces alike.

It’s the interaction between these two elements that will determine how MoMA’s latest changes will reverberate into the art trade. And a considered analysis leads me to believe that, unlike the reworked central staircase or refreshingly easy-breathing lobby, the most consequential effects demand some digging to uncover.

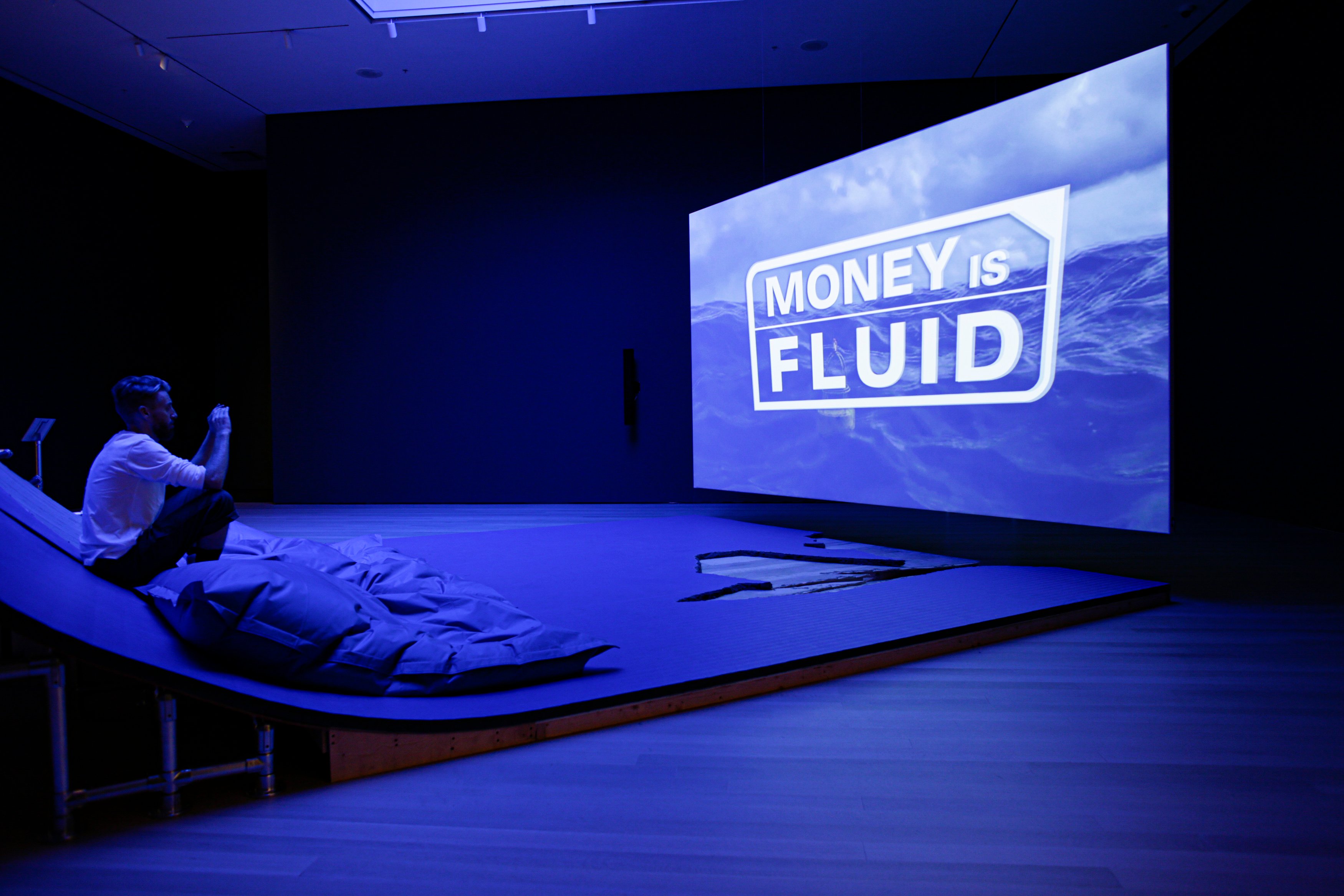

A look at the new MoMA, designed by architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro in collaboration with Gensler. Photo by Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images.

How Old Ideas Live On

Had DS+R and Gensler continued with the original vision unveiled in 2014, you’d be reading a very different analysis right now.

That splashier redesign is now best remembered for the proposed Art Bay, a physically and conceptually convertible, triple-height space that many critics, after the earlier reveal of DS+R’s plans for the Shed, treated as if it were yesterday’s math homework re-submitted with today’s date scribbled up top. Less enduring is the memory of the Gray Box, a smaller gallery directly above the Art Bay that would have been equipped with acoustic-absorption paneling and dedicated solely to performances.

The museum and architects composted both the Art Bay and the Gray Box in a chastened rethink of the expansion presented in 2016. A few tweaks aside, those updated plans gave us the MoMA we have today, one roughly 47,000 square feet larger than before, and dedicated largely to its permanent collection. This choice alone heavily affects the expansion’s potential impact on the art market.

That isn’t to say the earlier plans would have been the right choice, considering the decidedly mixed reviews for the Shed’s programming to date. For every rapturously received Arca performance, there seems to be a Norma-Jean Baker of Troy that sends theater-goers scurrying to the exits early. But MoMA’s need for an ongoing series of ambitious, site-responsive, marquee commissions would have registered on the art market’s Richter scale in a major way.

Instead, the expansion turns MoMA inward. While temporary exhibitions will continue to unfurl in most of the same designated spaces as in its prior iteration, the revamp is largely premised on maximizing the potential of its vast existing holdings.

Frida Kahlo, Fulang-Chang and I (1937). Image: Ben Davis.

I Think You Should Leave

This focus is underscored by the museum’s commitment to rotating one-third of its collection galleries every six months. On paper, the policy counteracts one of the inefficiencies that led MoMA director Glenn Lowry to propose that museums should “deaccession rigorously” to acquire great works or (if the major American museum associations would change their guidelines to allow it) build their endowments: that many, if not most, institutions own far more pieces than they can ever exhibit. To paraphrase University of California public policy professor Michael O’Hare, a vocal champion of selective deaccessioning, what cultural value are these legions of works providing from inside storage crates?

In actuality, though, MoMA’s cycling strategy comes nowhere near to solving the problem of its overcrowded storage. Lowry told our own Andrew Goldstein that the inaugural rehang comprises nearly 2,500 works, and the museum’s website states that its collection currently surpasses 200,000 objects. If MoMA stopped collecting today, but continued turning over the entirety of its permanent collections galleries every 18 months, it would still need more than 80 years to put everything it owns on view to the public just one time. I’m pretty confident Lowry and his colleagues aren’t doing celebratory keg stands over that ratio.

Will the collection’s regular churn make this problem obvious to the museum’s trustees and advisers, leading MoMA to bonsai its holdings with unprecedented urgency and at unprecedented scale? If so, that outcome would fertilize the market with thousands of works carrying impeccable provenance—better than even the most esteemed estate—in large part to equip the museum with the funding to fill the non-male, non-white, non-Western holes in its permanent collection.

I just find it hard to believe this will happen. Lowry’s comments show that MoMA’s decision-makers, from the curators to the trustees, were already well aware of this issue. Since they haven’t been compelled to embark on such a paradigm-shifting deaccession campaign before, I’m not sure why their minds would change after spending $450 million to make the museum bigger. And who can blame them, when selling a handful of works every few years provokes a throat-shredding outcry from certain segments of the art world?

The renovation could certainly nudge the museum to make a few targeted deaccessions to diversify the collection, as some of MoMA’s peer institutions have done recently. But short of spending the resulting funds on artists with almost no prior museum pedigree, this strategy wouldn’t cause a dramatic shift in the trade. Remember, private collectors now set an artist’s market by dint of having vastly more money to spend than public institutions. It would require a never-before-seen rampage of deaccessioning for MoMA to reverse that trend. Las Vegas could not generate odds favorable enough to convince me to bet more than a token amount on that outcome.

Does this mean that the revamped MoMA will have no effect on the art market, then? Not exactly. It just means the consequences are likely to be subtle.

David Tudor and Composers Inside Electronics Inc., Rainforest V (variation 1). Image: Ben Davis.

Everything in Moderation

Although the Gray Box was pine-casketed almost four years ago, its spirit lives on in the form of the new Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Studio on the museum’s fourth floor. Overlooking 53rd Street just west of the central staircase, the modestly sized space is the actualization of a unit innocuously labeled as a “new gallery/studio” in the 2016 rethinking of the museum. MoMA now bills the Kravis Studio as “the world’s first dedicated space for performance, process, and time-based art to be centrally integrated within the galleries of a major museum,” where it will alternately host everything from newly commissioned works and festivals, to residencies and workshops.

Yes, it’s a more limited gesture than the Gray Box would have been, let alone the Art Bay. But it’s not an insignificant one. In part two of his aforementioned interview with artnet News, Lowry defined “The Artist Is Present” as a “watershed moment” that clarified how performance would be “central to museums in the future.” MoMA is taking a step into that future by assigning a permanent and architecturally prominent space to this medium—a step none of its peers has taken, even as happenings and events have assumed greater importance in institutional programming worldwide over this decade. And when MoMA leads, everyone else in the museum sector still takes note.

Just as significant, though, is the fact that a major collecting family like the Kravises were willing to sponsor the performance studio. In a capitalist system, every art form is only as marketable as the size of its patron group. And given the follow-the-leader mentality that governs so much collecting behavior, performance could hardly ask for a better endorsement than being visibly co-signed inside MoMA by a billionaire couple consisting of the institution’s president emerita (Marie-Josée) and the namesake of an entire wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Henry).

In terms of commercial prospects, another noteworthy space occupies a double-height gallery at the west end of the ground floor. There, as part of the “Studio Museum at MoMA” series, MoMA will present one annual exhibition selected by the Harlem institution while its new David Adjaye-designed building is under construction. (MoMA PS1 will also host one exhibition per year by artists in residence at the Studio Museum.)

Given the past few years’ market momentum toward artists of color, particularly those anointed by Thelma Golden’s Midas touch, this collaboration provides an important platform for rising talent to gain traction with patrons during the Studio Museum’s hiatus. Michael Armitage, the subject of the first show in the series, has never had his work appear at auction to date. Let’s see if that changes in the next year.

Clockwise from top left: David Geffen; David Rockefeller; Leon and Debra Black; Alexandra and Steven Cohen; Ken Griffin.

What Matters Most

Beyond these modest elements, though, the revitalized MoMA has few other features with the potential to torque the art trade. Spacious, inviting, and well-trafficked as the new lobby may be, I don’t think it’s going to provide the American equivalent of Tate Modern’s lusted-after, sometimes trajectory-influencing Turbine Hall. The second-floor atrium remains unchanged from the Yoshio Taniguchi overhaul in 2004, even though that space is limited by its awkwardness.

Maybe the reworked restaurant and cafe will help lubricate sales by getting collectors’ blood sugar up so they don’t sleepwalk through a curator-led tour of the galleries… but if that happens on a scale that moves the needle in the overall market, frankly, it’ll be time for all of us to reevaluate a lot of things about our lives.

In the end, just as my colleague Ben Davis felt that MoMA’s initial rehang did more to reinforce the established canon than to atomize it, the museum’s expansion does more to reinforce the art-market status quo than to disrupt it. The Kravis studio matters, as does an exhibition of Latin American works from a major gift by media magnate Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. But two freshly christened, much larger spaces arguably matter more.

The museum’s nearly 50,000 square feet of augmentations to the west are known as the David Geffen Wing, in recognition of the mega-collector’s $100 million donation in 2016. Its sixth floor, still dedicated to temporary shows, has been named the Steven and Alexandra Cohen Center for Special Exhibitions, in honor of the couple’s $50 million gift to MoMA in 2017. Although there are no visible signifiers of its presence inside the renovation, the museum also benefited from an estimated $228 million from the late David Rockefeller since 2017, as well as additional major donations from familiar faces like Ken Griffin and Debra and Leon Black.

Geffen, Cohen, and their contemporaries have certainly been generous to institutions and beneficial to their favorite artists’ prospects over the past few decades. Rockefeller’s transformative impact on the art world outlives him. But in an American museum system still largely subject to the preferences of super-rich private patrons, it’s important to recognize that the new MoMA was largely made possible by checks bearing the same old signatures. If that fact doesn’t tell us something meaningful about the limited degree of change we should expect the revamped institution to have on the market, we’re not listening closely enough.