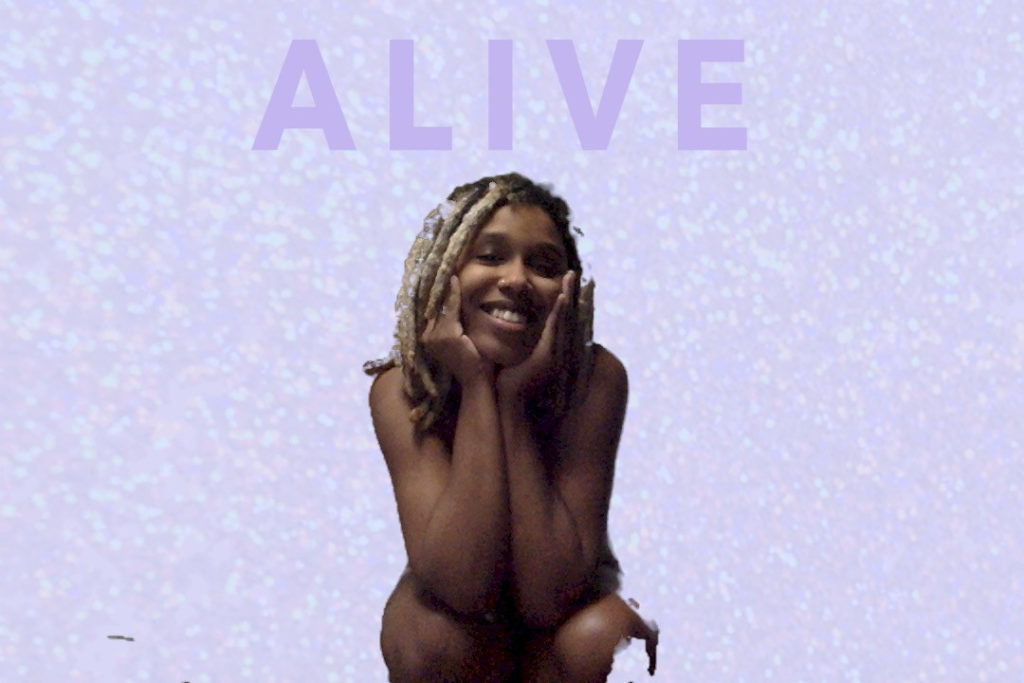

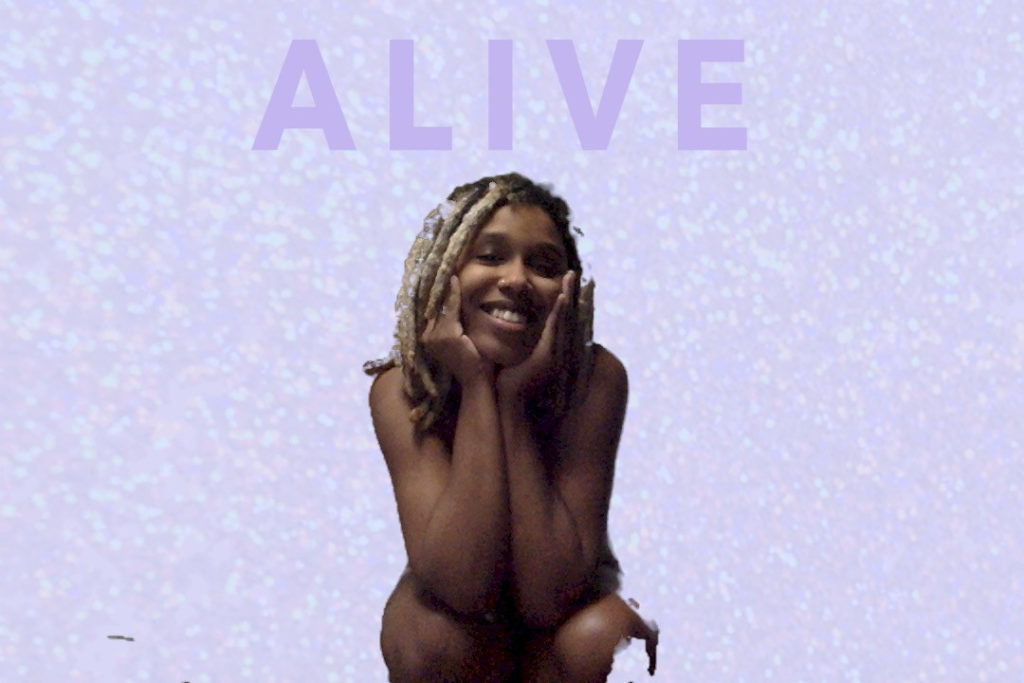

In 2015, the artist E. Jane began uploading selfies taken by black women to a website under the banner “Alive.” The aim was to show that while Sandra Bland, who had died earlier that year, was no longer living, other black women are. The artist (who uses they/them pronouns) and others posted the images to social media with the hashtag “notyetdead.”

A few years later, E. Jane included the “Alive” project in an application for the Studio Museum in Harlem’s artists-in-residence program. The residency is one of the most competitive and closely watched initiatives of its kind in the country, with more than 100 alumni including Kerry James Marshall, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, and Simone Leigh. But it has a reputation for selecting mainly painters, not performance or new-media artists. Still, E was encouraged to apply after visiting alumnus Eric N. Mack during his residency—and they ended up being the first internet artist the program has ever accepted.

This year’s cohort—which also includes musician and performance artist Elliot Reed and painter Naudline Pierre—may suggest a shift for a program that has been exceedingly influential as a career-defining platform for generations of black artists. And that shift will likely have broader implications for the kind of art that makes its way into the market and institutions for years to come.

Still, some wonder, as the field continues to grow, whether one program—while exceedingly valuable to many of its alumni—should hold so much responsibility in shaping the discourse on black contemporary art.

E. Jane, Alive (Not Yet Dead) (2015). Courtesy of the artist.

Filling a Void

There’s something about the story of the Studio Museum residency that’s hard to crack. The program, which dates back to the museum’s founding in 1968, provides three artists of African and Latinx descent each year with studio space for 11 months in New York City and a $20,000 stipend.

Most residents feel relieved, after years spent navigating majority-white art schools or other institutions, to finally be around other black people—from curators to secretaries to security guards. “I was so excited to be around folks who look like me, who just understood the weird contradictions,” says Jibade Khalil Huffman, who was part of the 2014–15 cohort with now-prominent artists EJ Hill and Jordan Casteel.

Hill concurs. “At school or other professional workplaces, my shoulders were up near my ears,” he says. “I got to relax a bit there.”

EJ Hill, Excellentia, Mollitia, Victoria (2018.) Installation and durational performance. Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles. Photo: Chisa Hughes.

This environment can be creatively fulfilling and reassuring in ways artists haven’t experienced elsewhere. Bethany Collins, who participated in the residency from 2013–14, says she was grateful that discussions about her work were not cut short by a disinterest in talking about race, a problem she confronted quite a bit in graduate school. “Some of the critiques I got were, you know, ‘I don’t see race so I just can’t critique this work,’” she recalls. “So that’s not helpful.”

Nearly every artist I spoke to had a strong reaction to the news that two performance artists had been chosen for this year’s residency. While they had different ideas on what, exactly, the year’s selections signaled about the museum, they all felt that the decision meant something—a strategy while the museum is closed for its $122 million expansion, perhaps, or, more fundamentally, a sign that the museum is deepening its commitment to non-object based art (and, therefore, to artists with less established career paths and market opportunities).

Market Impact

The Studio Museum residency has taken on heightened significance as the market for work by black artists has grown. When Wardell Milan II went through the program more than 10 years ago, he and black artists of his generation “definitely saw it as a launching pad, because so few of us during the 2000s were represented by significant galleries,” he says.

By the time abstract painter Cullen Washington nabbed the residency in 2011, meanwhile, he felt comfortable enough with the visibility the residency afforded to set securing gallery representation as his goal for it.

According to Patricia Banks, author of Diversity and Philanthropy at African-American Museums, the market interest in artists of African descent has seen a “nice, steady uptick” from the late ‘90s into the 2000s, followed by a much steeper incline over the past five years. She attributes some of this movement to Studio Museum director Thelma Golden’s effort to raise the symbolic capital of black art, and, in turn, the profile of the museum in choosing it.

The facade of the Studio Museum Harlem. Courtesy Adjaye Associates.

“Because the work is in the marketplace in a more meaningful way,” Banks says, “there might be more sensitivity to the role of black museums in legitimating culture” to the broad cultural world.

Many are quick to note that the Studio Museum’s artists in residence have often been somewhat industry-tested. They’ve gone through the Yale MFA program or the Skowhegan residency, or had run-ins with assistant or associate curators, who sometimes scout for new talent.

Although none of the upcoming residents were “previously known to everyone on the selection committee,” associate curator Legacy Russell wrote in an email, she had been acquainted with E. Jane for years. After being introduced through a mutual friend, Russell put E. Jane in a show on digital art.

Exceedingly Influential

From the moment that Golden arrived at the Studio Museum in 2000 and curated “Freestyle,” a show that characterized the work of 28 black artists as “post-black” (a term meant to indicate that they no longer wanted an ethnic label to constrain their work), the black art community has been evaluating the museum’s deployment of this mandate. And the residency program is one stage for it to play out on.

After “Freestyle,” Clifford Owens, for one, applied to the residency, thinking it would be a hospitable place for his performance-based practice. “The residency, and the museum at that time, was at the center of the [post-black art] discourse,” he says. “It just seemed appropriate for the work that I make to be there.”

Director and Chief Curator of The Studio Museum in Harlem, Thelma Golden. (Photo by Mireya Acierto/Getty Images)

But over time, the residency’s selections seemed to crystallize a particular point of view for the institution. Many say the museum has remained committed to figuration and work with clear signifiers of the black body.

Opinions differ on how much the museum balances those aesthetic leanings with other types of work. Milan, who went through the residency in 2006–7, says, “I can remember a time when we wouldn’t see a certain kind of work at the museum.” He felt as though the institution steered clear of more “difficult” work—like performances by artist Kalup Linzy, for example—in order to represent blackness in a digestible way, genre aside. But he adds that he thinks the residents have gotten far more aesthetically and conceptually diverse in recent years.

Artist Lyle Ashton Harris, meanwhile, maintains that along with supporting “artists who have gone on to robust commercial success, the institution also has a strong mandate to support discursive events” like his Michael Jackson-themed performance Performing MJ.

What Is Black Art, Anyway?

What type of work fits within the Studio Museum’s wheelhouse at any given moment is a complicated equation to solve. The interests of the institutional stakeholders are fluid and are only known to a select few. Also, as artist Xaviera Simmons notes, what’s considered “of the moment,” authentic, or radical shifts over time, is contingent on who’s looking, and is shaped by the institution’s place (and function) within the broader art community.

Autumn Knight, Sanity TV: On Location, 2018. Performance view, Akademie der Kunste, Berlin. Courtesy of the artist.

But the fact remains that the announcement of the Studio Museum’s residents behaves as an annual signal to rethink how the museum is spearheading the conversation on black art—with artists continually trying to gauge what kind of work the museum likes in order to become part of its distinguished legacy.

Autumn Knight, who came out of the program two years ago, jokes that she moved from Houston and arrived at the museum expecting “a council of elders to welcome me.” She felt that as a resident at the Studio Museum, she had access to a “vault of black art knowledge that goes back centuries.”

Acceptance into the Studio Museum’s residency program is not just an avenue for commercial success. Derek Murray, a professor of art history and visual culture at the University of California, Santa Cruz, suggests that “it’s also about racial legitimacy and being valued by one’s culture.”

While the Studio Museum is, Russell writes in an email, responsible to “answer to and reflect the world around it,” many wonder how much any single institution, especially one almost single-handedly changing the course for black art within such a conservative, white-dominated space, can realistically take on.

As a result, the museum is faced with the same dilemma that Golden and artist Glenn Ligon were trying to correct for when they established the post-black art dictum at the start—how no one term or, in this case, institution, can preside over the totality of what black people make.

Jordan Casteel, Cowboy E., Sean Cross, and Og Jabar (2017). Photo: Jason Wyche, courtesy the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York.

Membership Benefits

“I think there are conceptions of what comes out of the Studio Museum program that is potentially pandering, but if you actually pay attention over time,” says 2007–8 resident Saya Woolfalk, the museum “is constantly supporting all sorts of different kinds of voices.” She considers the residency an area where “curators are given the latitude to experiment.” For her, and many others, the museum’s backing, through friendships and connections, continues to pay tremendous dividends.

Huffman also acknowledges that the museum’s plugged-in curators, who canvas for the residency, provide an important breeding ground for unconventional work, but feels like there should be room for more. Five years after his time at the museum, he feels cut off from the institution and has a strong feeling that what he made didn’t quite fit into the wider institutional agenda. He and others say that while its aesthetic mission is meaningful and potentially paradigm-shifting for black art, it can’t possibly represent the entire field of black art-making (which, incidentally, the museum itself was instrumental in opening up).

Regardless of the extent of his engagement with the museum after the residency ended, Huffman still considers himself part of the Studio Museum network, a sentiment echoed by many alumni. “I feel like you’re always part of the family,” says Abigail DeVille, who participated in the residency in 2013–14. “If you need support, like in terms of promotion of a project that you’re doing? [The museum is] just down for you, period, like you’re in the fold now.”

Abigail DeVille, Only When Its Dark Enough at the Contemporary, Baltimore. Courtesy of the Contemporary and the artist.

A Model of Success

As the director of another black Harlem-based institution, the Sugar Hill Children’s Museum of Art, Lauren Kelley understands how many interests a person like Thelma Golden, and the Studio Museum as a whole, must balance.

“When I was just an artist in Texas, with my nose pressed up against the glass, I couldn’t understand why I got that rejection letter [from the residency],” Kelley says. “I can’t go into all of what the mystery [of the museum’s selections] is about, but I know it’s a lot more complicated than just, ‘they don’t like me.’”

In some ways, Golden’s role is so inscrutable because she is defining it as she goes along. In addition to managing stakeholders with different priorities, Patricia Banks explains, Golden has built enough symbolic capital, by strategically positioning the museum as the main arbiter of good black art, to establish the Studio Museum as a dominant institution within the African-American art world and beyond. As a result, she has been able to shore up significant financial resources. “Success begets more success,” Banks says. “Influence begets more influence. Donations beget more donations.”

By being the most prominent program of its kind, the museum must carry an outsize burden in deciding what reflections or representations make the cut. Perhaps that’s why, symbolically, the Studio Museum in Harlem has become such a huge force, when in fact, the organization is rather small—its operating budget is just $6 million (for comparison, the New Museum’s is $13 million and MoMA’s is $147 million).

Looking ahead, the museum is working to cultivate artists and curators who go on to build their own institutions. Two residency alumni, Kehinde Wiley and Titus Kaphar, have established their own residency programs in Dakar and New Haven, respectively. With any luck, an ecosystem is developing in which the Studio Museum is no longer the only institution that artists and the broader art community look to for guidance on the future of black art.

“I personally know lots of people who have blown up, that are basically canonized artists, that did not get into the Studio Museum,” Abigail DeVille says. “At the end of the day, there really are only three spots.”