Politics

‘We Want to Feel Free’: At These 4 Fringe Galleries in Moscow, Artists Are Avoiding Government Censors

To avoid government restrictions, some artists are setting up their own fringe spaces.

To avoid government restrictions, some artists are setting up their own fringe spaces.

Rachel Corbett

On the northeastern edge of Moscow, a group of artists have turned a factory that once manufactured long-range radars for the Soviet military into a complex of studios and exhibition spaces. The company, NIIDAR, shut down the facility in 1989, but tight security still restricts access to the building.

When I visited earlier this spring, I presented my photo ID to a security official at the door before passing through to an icy courtyard. I walked nearly half a mile to the next building and then up some icy steps to reach the experimental artist-run space APXIV (pronounced archiv). Inside was a cluttered workshop with high ceilings and pink curtains where members of the collective, also called APXIV, were hanging out in coats and hats drinking tea.

Maria Cheloyants, an artist and graphic designer, tells me they prefer their makeshift spaces in NIIDAR to the white cubes in the center of town that cater more to Moscow’s elite. “At a gallery you have restrictions and people have to be careful,” she says. “That’s why we have our own space. We want to feel free.”

The post-Soviet promise of democracy has withered over the past three decades. But if the artists Russia has produced in this time are any indication, the urge for political accountability and free expression hasn’t.

Several Post-Soviet Actionists—the term sometimes used to describe the protest artists who have emerged in the past 30 years—have risen to international recognition, including members of Pussy Riot, who were imprisoned for performing an anti-Putin song from the rooftop of Moscow’s largest cathedral; Pyotr Pavlensky, who nailed his scrotum to the Red Square; and Oleg Kulik, whose work often involves chaining himself to people like a dog.

And although artistic insurgency in Vladimir Putin’s Russia has resulted in jail time for artists, the firing of curators, and the handover of museums to oligarch decision-makers, avant-garde artists working in Russia today haven’t been entirely silenced. They’re just operating on the fringes—in old factories and apartment buildings, in fleeting one-night events that are over before word even spreads.

We visited some of Moscow’s off-the-radar venues to see art outside the mainstream.

Work by young Kranoyarsk artists at Simon Mraz’s apartment gallery, The Boom Rooms. Photo by Frank Herfort, courtesy of Simon Mraz.

There’s a long tradition of apartment shows—known as kvartirnik—in Moscow. In the Soviet era, private homes were among the only places where non-conformist art could be shown. Simon Mraz, an attaché for the Austrian embassy in Moscow, continues that legacy by using his 750-square-foot apartment in one of the most famous buildings in the city, the House on the Embankment, as a gallery for emerging artists.

“There are a lot of artists without galleries,” he says. “For up-and-coming artists, it is nice to be visible without any pressure to feed institutional expectations, or have them control any of the content, without the needs of any curators, experts, whoever.”

The space itself is symbolic: a late Constructivist building that Stalin built for the city’s elite on the banks of the Moscow River—what Mraz calls “an architectural monument as well as a symbol of suppression—all with a window view to the Kremlin.”

Next up, he plans to show works by the Russian-Korean aritst Sasha Kim and the late Russian artist Valery Isayants, who was homeless for the last 20 years of his life, but continued drawing and working the entire time. He was beloved by the creative community in his hometown of Voronezh, Mraz says, “but for some strange reason, he’s never been seen in Moscow.”

Mraz is also planning a show of young artists from St. Petersburg because, he says, “for whatever reason artists from St. Petersburg are underrepresented in Moscow.”

The shows are all open for one evening only, but Mraz makes an event out of each by providing “wine and water, a big pot of food, and a balcony for the smokers”—and, most importantly, a space “to really create something artistically important, but in an environment where the artist hopefully feels at home, trusted, and respected.”

Gallerist Dima Filippov and artist Elizaveta Veselova at Electrozavod, Moscow. Photo: Rachel Corbett.

A group of artists established this 2,100-square-foot gallery in a former Soviet electrical plant in 2012. Although it looks like a traditional white cube on the inside, it doesn’t operate like one. For one thing, the artists who show at Electrozavod are usually responsible for selling their own work and, when they do, the gallery doesn’t take a cut. The only time when the gallerists conduct sales is on one designated “sales day” per year.

“We do it to have money for the technical support of the gallery,” says artist and Electrozavod co-founder Dima Filippov. “Prices are really cheap. Often the buyer realizes that he does not just buy the work from the artist, but supports the activities of the gallery.”

The kinds of shows that Electrozavod puts on are different from those in traditional Moscow galleries. “Under conditions of censorship in state and private museums, artists sometimes can show here what they cannot show elsewhere,” Filippov says. “All the founders of the gallery are artists and this leaves its mark on the style of work with invited artists. We do not load them with the bureaucracy and deadlines. I think it also leaves a mark on the final result—the exhibitions are more experimental, but we still try to do everything with the maximum quality.”

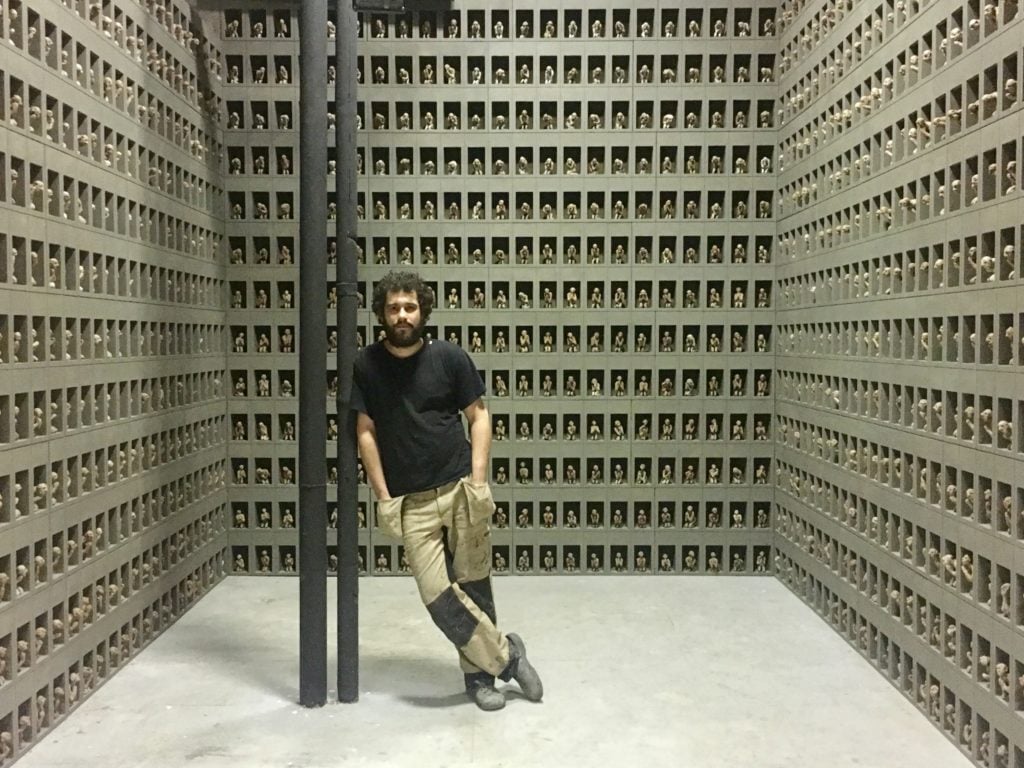

Artist Andrey Kuzkin with his installation Prayers and Heroes at his studio in Proekt Fabrika. Photo: Rachel Corbett.

After operating a run-down paper factory for 15 years, the manager of the complex decided to turn it into a non-profit art space in 2005. “I come from a family of artists, so at first I asked them for advice. ‘Should I do it?’ And when they said, ‘yes, you should,’ I just started it,” says Asya Filippova. Today the space houses two galleries, a theater, a publishing house, 10 artist studios, and a residency program.

On a recent visit, one of the current resident artists, Andrey Kuzkin, had just installed in his studio the fruits of two-and-a-half years of work: 1,104 little men made out of bread in a grid of cells. They at once symbolize the religious belief in bread as the body of Christ, and the Russian prison culture of inmates making bread, Kuzkin says. “So it’s two traditions come together, from the actual prison and the Christian idea that the body is the prison of the soul.”

Kuzkin had installed the work for an open studio event that was taking place at the former paper factory the night after my visit. He said the hope was “not to sell the work, but to find ways to show it in good places, like museums or big institutions.”

For money, Kuzkin applies for grants, crowd-funds, or sells his work on Facebook. He used to work with a gallery, but they went out of business. Now he says he prefers to work independently. “The system I use,” he says, “gives me more freedom.”

Romantic Bath for a Single Lover at APXIV. Courtesy of APXIV.

When some of APXIV’s members participated in an exhibition at Moscow’s Institute of Contemporary Art a couple years back, “every artist faced some restriction,” the dozen or so members of the collective tell artnet News in a group email. That’s why they decided to form the collective in 2017, which they describe as a “spatiotemporal structure in the constant process of transformation.”

“Running our own space enables us to reduce the restrictions and do whatever we want, including the presentation of our bodies,” they say. In one show titled “Underwear,” they imagined that censors had been given a “day off” and that artists were now free to address topics that “are normally suppressed both by institutions and our own views and concepts,” according to the exhibition statement.

That involved stringing up condoms from the ceiling, and, for one artist, taking a bath in a tub in the gallery surrounded by candle flames. “That combination would be definitely impossible pretty much anywhere else in Moscow,” the collective writes in the email.

Unfortunately, the APXIV space may not last much longer: the artists have been informed that the building will soon be demolished to make way for a shopping center.