Politics

The National Geographic Society Wanted to Destroy Its Celebrated Outdoor Sculpture to Create a Plaza. Now a Fierce Backlash May Save It

The sculpture in question was installed in 1984 by artist Elyn Zimmerman.

The sculpture in question was installed in 1984 by artist Elyn Zimmerman.

Sarah Cascone

Plans to renovate and expand the entry plaza of the National Geographic Society in Washington, DC, which would have included the controversial removal of Marabar, an acclaimed 1984 sculptural installation by American artist Elyn Zimmerman, have run into a speed bump.

After getting more than two dozens letters of protest regarding the proposed removal of the artwork, including one from Adam Weinberg, the director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the city’s Historic Preservation Review Board has reconsidered its approval of the project, which was issued last August.

The board is now advising the National Geographic Society to revise its blueprints and “strongly consider retaining the sculpture in some form, possibly relocating it somewhere on the site as part of a new concept, or if not, why that is not at all possible,” said panel chairwoman Marnique Heath at a meeting yesterday, as reported by the New York Times.

“I was delighted and a little surprised,” Zimmerman admitted to Artnet News. “I didn’t have much hope. I’ve heard from a lot of artists who make work in the environment, and everybody has their war stories… There’s not a good track record for saving a lot of these art pieces.”

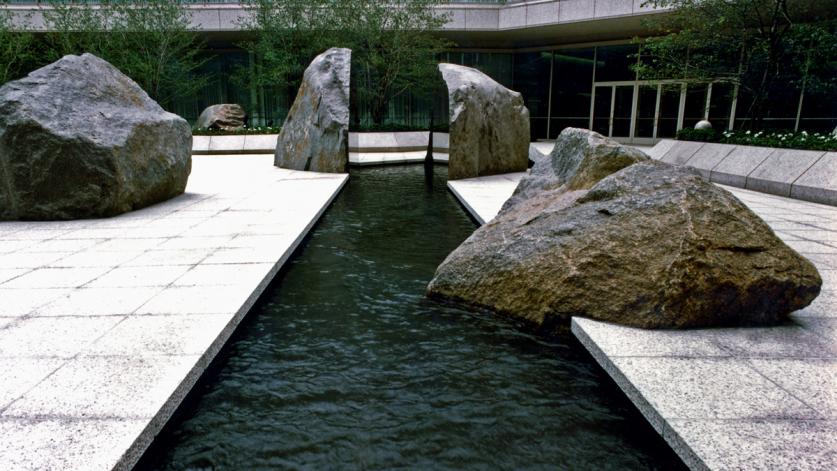

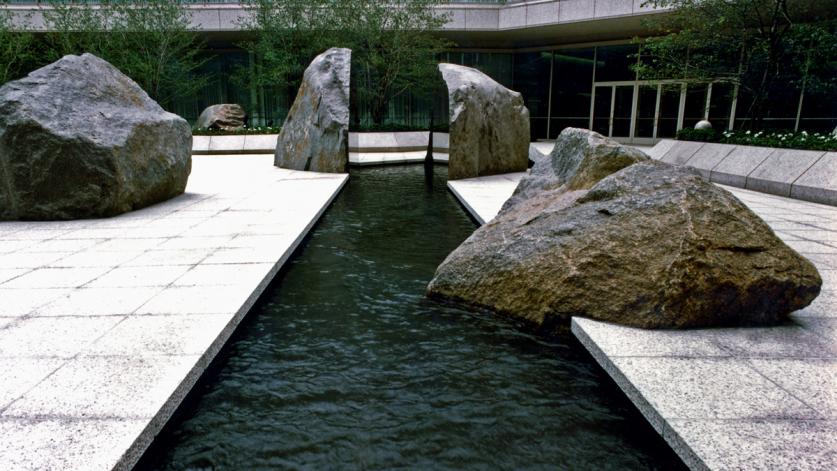

Elyn Zimmerman, Marabar (1984) at National Geographic Society Headquarters, Washington, DC. Photo courtesy Elyn Zimmerman.

The advocacy group the Cultural Landscape Foundation mounted a campaign to save the work on March 31 as part of its efforts to preserve threatened works of landscape architecture. The organization argued that the National Geographic Society had neglected to mention the artwork or its importance in presenting its initial renovation plans from Hickok Cole Architects.

Foundation CEO Charles A. Birnbaum applauded the board’s decision to reconsider granting project approval, and urged National Geographic in a statement to work with its architects and Zimmerman “to develop a design that meets the society’s programmatic needs and retains Marabar.”

The society declined to comment on the decision, but had argued previously through a lawyer that “Marabar is not historic” and that its removal was necessary to build a much-needed entrance pavilion that would provide one singular access point to its three main buildings.

“There’s enough room there to accommodate both things, I believe,” said Zimmerman, who is open to helping draw up solutions that might involve enclosing Marabar within the pavilion. “I’m hoping that National Geographic and their new architects will consider having me as part of their team.”

A rendering of the proposed pavilion and plaza that National Geographic is preparing to build at its headquarters in Washington, DC, in place of Elyn Zimmerman’s sculptural installation Marabar. Image courtesy of Hickok Cole.

When the society first decided to remove Marabar, the project architects invited Zimmerman to relocate the piece at the National Geographic’s expense.

“They said they were going to remove Marabar, and would I like to come by and pick up the rocks,” Zimmerman recalled. “For a minute I thought it was a crank call! Like I’m going to drive by with my pickup truck and grab a quarter-of-a-million pound stone.”

Zimmerman claimed she was unable to find a suitable alternative home for the massive, technically complex work, which involves a hydroelectric system to keep water flowing. Mined from a granite quarry in South Dakota, the boulders in the work collectively weigh over a million pounds, and were installed in their current location only after the plaza was engineered to hold them.

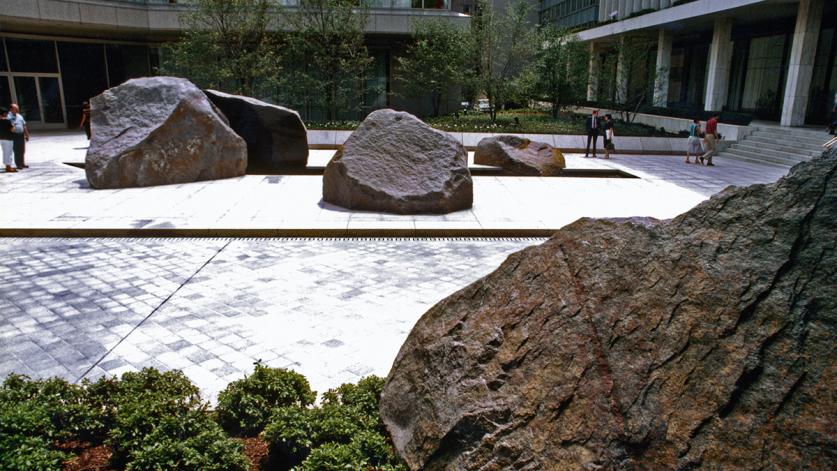

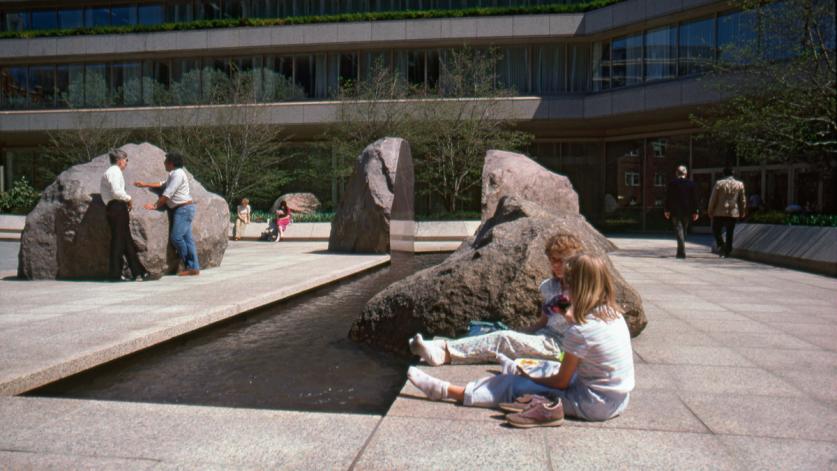

Elyn Zimmerman, Marabar (1984) at National Geographic Society Headquarters, Washington, DC. Photo courtesy Elyn Zimmerman.

“I don’t know if it can be moved physically,” Zimmerman cautioned. “It’s not impossible, but it would be very difficult.”

Named after the Indian caves featured in E.M. Forster’s “A Passage to India,” Marabar features five boulders surrounding a 60-foot-long rectangular pool of water. It was the artist’s first large-scale and permanent public artwork.

Before the Cultural Landscape Foundation got involved, the artist didn’t believe it would be possible to oppose the will of National Geographic, which is owned by corporate giants 21st Century Fox and Disney.

“I’m too old to waste the last few years of my life fighting them,” Zimmerman said. “I was resigned to the fact that it was going to be destroyed.”