Crime

The Founder of Netscape Has Returned $35 Million Worth of Looted Cambodian Antiquities

James H. Clark bought the works between 2003 and 2008.

James H. Clark bought the works between 2003 and 2008.

Sarah Cascone

Technology entrepreneur James H. Clark, creator of the once dominant Netscape browser, has surrendered 35 Southeast Asian antiquities from his personal collection after federal investigators determined they had been looted. Twenty-eight were from Cambodia and the rest from India, Myanmar, and Thailand.

Clark purchased the pieces for roughly $35 million between 2003 and 2008 from the disgraced dealer Douglas Latchford. Long considered a leading Cambodian art scholar, Latchford was later alleged to have operated a smuggling enterprise for decades, trafficking systemically looted antiquities through Thailand, where he lived. By the time he died, in 2020, he was facing charges of trafficking Southeast Asian antiquities.

“Today, we are pleased to see that 35 pieces of cultural property will be repatriated to their rightful setting,” Ricky J. Patel, acting special agent-in-charge of the New York office of the department of homeland security, said in a statement. The department, he added, “will not rest in its efforts to locate all the antiquities related to Latchford’s fraud and see that each piece of history is not just found, but sent home.”

A court complaint filed this week cites numerous emails from Latchford to an unidentified dealer that clearly identify sculptures he had sold to Clark as new, illegally excavated discoveries—rather than works that had left the country prior to the UNESCO 1970 Convention prohibiting illegal trade in cultural property.

British Khmer art collector Douglas Latchford during a function at the National Museum of Cambodia in Phnom Penh on June 12, 2009. Photo by Tang Chhin Sothy/AFP via Getty Images.

One was “fresh out of the ground, and needs to be cleaned,” and for another “they took off most of the mud, or as it was, a sandy soil.” A third email enthused, “hold on to your hat, just been offered this 56 cm Angkor Borei Buddha, just excavated, which looks fantastic. It’s still across the border, but WOW.”

To convince Clark the artifacts had been acquired legally, Latchford drew up paperwork with false provenances stating works had been exported in the 1960s, or had belonged to overseas collectors for decades.

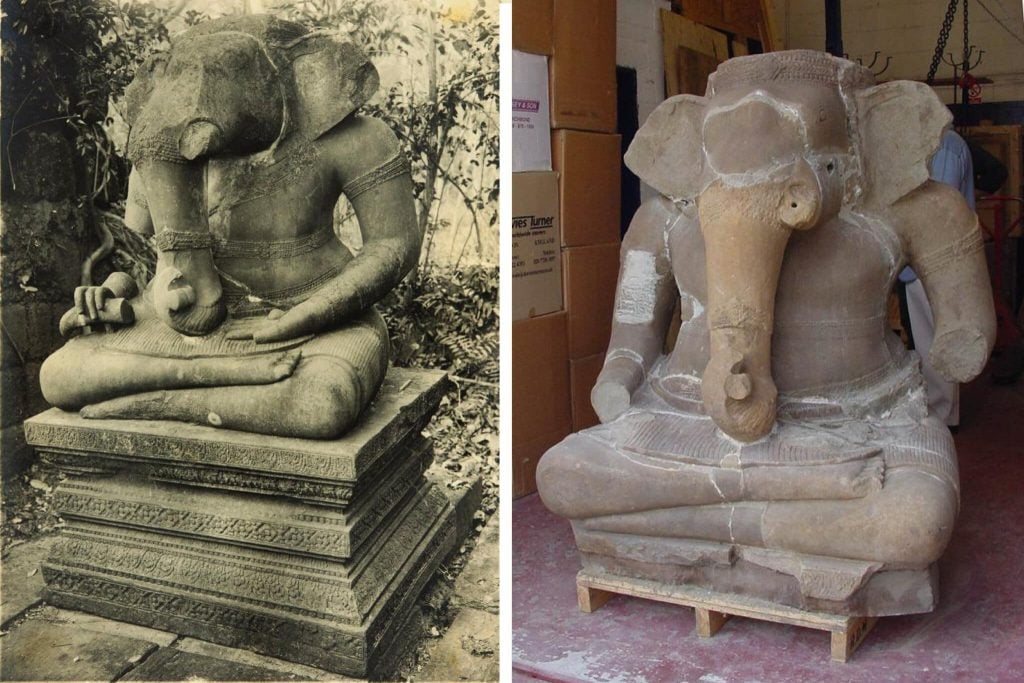

One well-known statue of the the elephant god Ganesha was a “near-twin” of “the famous published one [that] has disappeared,” he claimed. Cambodian experts believe Clark was actually sold the stolen original, photographed by French archaeologists in 1934.

When investigators presented this evidence to Clark, he agreed to return the collection to Cambodia.

At left is Ganesha statue in Cambodia photographed by French archaeologists in 1934. On the right is what Cambodian officials believe to be the same piece in James H. Clark’s storage unit. The late dealer Douglas Latchford is accused of having looted and sold the work to Clark, who has agreed to repatriate it. Photo courtesy of the Cambodian Government.

“I was freshly wealthy in the early 2000s,” Clark told the Washington Post. “I naively accumulated a bunch of pieces through Doug Latchford, and it wasn’t until near the end that I thought: ‘You know, this isn’t quite stacking up right.’”

Clark said he grew suspicious and stopped purchasing work from the dealer in 2008, when there was no satisfactory provenance for a statue of a female deity that Latchford was selling for over $30 million.

“I wanted some Cambodian government authentication of this thing and he would not respond to those messages, and I finally just said, ‘There’s something wrong here—this guy is a bit of a crook,’” Clark told the New York Times. “I had kind of concluded that it was something illicit because he would not respond to those requests.”

Evidence of Latchford’s wrongdoing first came to light in 2012, when the U.S. government filed a federal forfeiture action in 2012 against Sotheby’s over a looted work the dealer had previously sold.

New information about Latchford’s illicit dealings came to light in October with the leak of the Pandora Papers, a 2.9 terabyte cache of 11.9 million documents revealing the offshore financial transactions of some of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful people.

Included in the leak were documents proving that Latchford had established two trusts, named after the Hindu gods Skanda and Siva, on the Island of Jersey, in the Channel Islands between England and France. The trusts could have helped Latchford obscure his ownership of both art and money—and news of their existence cast more doubt on other Asian antiquities that had passed through his hands.

An Angkor Wat-style bronze sculpture depicting seated Buddha. Photo courtesy of the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York.

For years, Clark had displayed his collection of Cambodian statuary in his Miami Beach penthouse. But the works have been held in storage in Palm Beach for the last decade, because his interior decorator “wasn’t excited about it,” Clark told the Post.

With Clark’s cooperation, authorities seized the works from the storage units. The collection is expected to be repatriated within the next six months. For the 28 Cambodian sculptures, the hope is that they will one day appear in a special wing at a new Cambodian national museum, along with other works smuggled by Latchford.

Last February, Latchford’s daughter agreed to repatriate his $50 million collection of some 125 Khmer antiquities to Cambodia. The Denver Art Museum also announced that it would restitute four Cambodian antiquities that Latchford had once owned.

More returns could follow, as the British Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art all own multiple works once associated with the dealer. (The Met previously repatriated a pair of looted Latchford-owned sculptures to Cambodia in 2013, and the nation has provenance concerns about 45 other potentially looted items at the museum.)

Though questions of looted artifacts and repatriation have proven to be thorny in the museum world, for Clark there was only one solution. “Why would you want to own something that was stolen?” he asked the Times. “I’m very pleased that they are going to be shown in a museum now where people can really appreciate them.”