Politics

The US Army Is Launching a 21st-Century Version of the Monuments Men to Protect Cultural Heritage in War-Torn Regions

The new Monuments Men are here.

The new Monuments Men are here.

Sarah Cascone

The Army is putting its curators, conservators, and archaeologists to work thanks to a new reserve group that brings the Monuments Men and Women of World War II into the modern era. The next generation of Monuments Men will, like their predecessors, be dedicated to protecting the world’s cultural heritage during times of war, this time with a focus on the Middle East.

The Pentagon announced the new initiative, a partnership with the Smithsonian Institution, on Monday, when representatives from both bodies gathered at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art in Washington, DC, to sign an agreement. The volunteers, who will be trained by the Smithsonian, are officially titled Cultural Heritage Preservation Officers.

“In conflict, the destruction of monuments and the looting of art are not only about the loss of material things, but also about the erasure of history, knowledge, and a people’s identity,” Smithsonian ambassador-at-large Richard Kurin told the New York Times. “The cooperation between the Smithsonian and the US Army aims to prevent this legal and moral crime of war.”

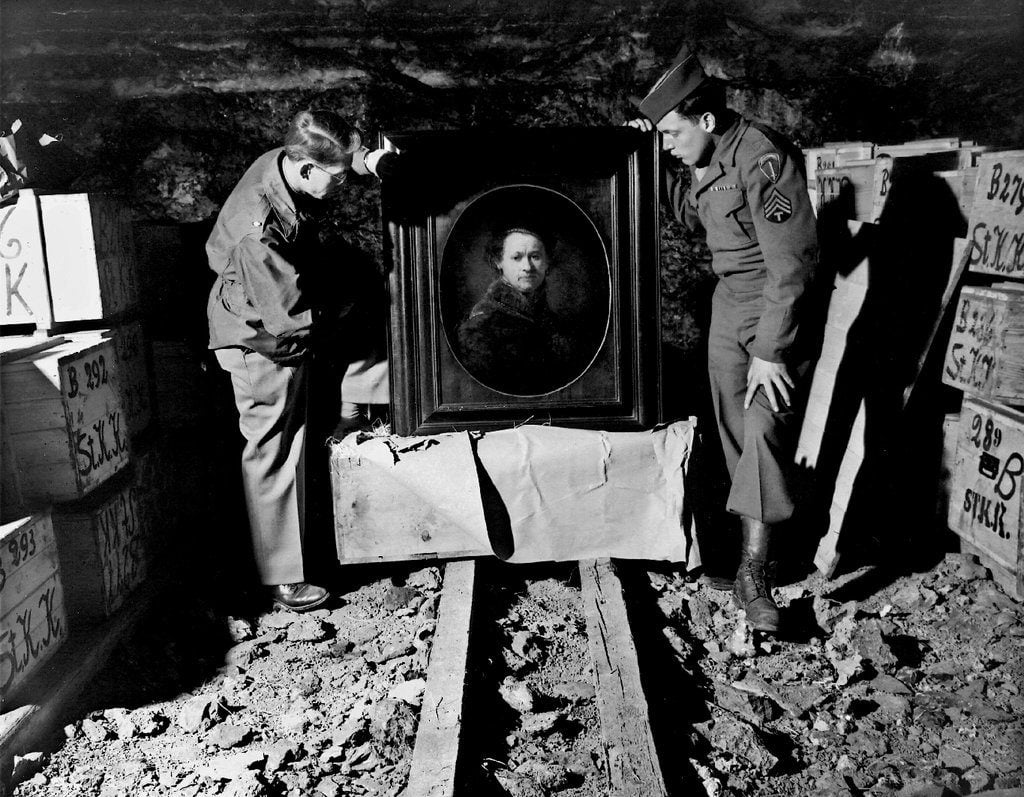

The original Monuments Men were part of the Army Civil Affairs Division, and included 345 curators, architects, art historians, and other art professionals. Their work between 1943 and 1951—which inspired the 2014 George Clooney film The Monuments Men—helped save many of Europe’s cultural treasures, and memorably recovered artworks looted from Jewish owners by the Nazis and hidden castles and salt mines.

A Rembrandt self-portrait recovered at a German salt mine that had been used as a storehouse, with Harry L. Ettlinger, right. Photo courtesy of the Monuments Men Foundation.

There have been discussions about bringing back the Monuments Men for some time, with the US Army Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command specifically seeking out cultural specialists in 2015. Since then, “it’s a been a gradual recruiting effort,” Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative director Cori Wegener, who served as a Civil Affairs Arts, Monuments, and Archives officer in Iraq, told artnet News. The program will be staffed by commissioned Army reserve officers with arts expertise.

Wegener has maintained relationships with the armed forces since leaving the military, and, over the past few years, has led workshops at the Smithsonian to train military personnel in matters of cultural preservation on an ad-hoc basis. But where those efforts have been limited to daylong events with civil affairs generalists, the new arrangement will see the Smithsonian hold a week-long workshop in March for officers who already specialize in the field.

“We’ll be learning from each other—these are people who already have a background and expertise as cultural heritage professionals,” said Wegener. “It’s a really historic agreement between the Army and the Smithsonian.”

An Iraqi soldier stands on November 15, 2016, on the ruins of the archaeological site of Nimrud, which were severely damaged by ISIS. Photo courtesy SAFIN HAMED/AFP/Getty Images.

Today, the world’s most vulnerable areas are perhaps in the Middle East, home to ancient historic sites settled by mankind as many as 10,000 years ago. Over the past two decades, there has been considerable cultural destruction in countries such as Syria—ISIS in particular has devastated the region.

The focus of the new Monuments Men will primarily be on keeping military leaders informed about the potential risk that armed conflict puts on historic landmarks and other culturally significant objects. The officers will work closely with local leaders to enable them to protect their own cultural heritage, creating protocols to safely evacuate museum collections and rebuild after disasters.

The new Cultural Heritage Preservation Officers will advise the armed forces about areas where air strikes or ground combat might threaten cultural sites, and about places that might be at risk of looting. That’s something the US military could have been more proactive about in 2003, when the Iraq National Museum in Baghdad was plundered as the city fell, despite warnings from archaeologists and State Department officials.

Since that time, the US joined, in 2009, the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property, an international treaty aimed at protecting cultural heritage during combat. “Each county is supposed to work to make sure their military understands their responsibility of protecting cultural heritage and to avoid damaging that heritage during armed conflict,” said Wegener. “It’s an ethical and moral responsibility of all cultural institutions around the world.”

The Congressional Gold Medal presented to the Monuments and Women in 2015. Photo courtesy of the Monuments Men Foundation.

Signing the agreement for the new military group at the Archives of American Art, which contains many archival records pertaining to the original Monuments Men, “reminds us of our country’s important legacy in protecting cultural heritage in wartime,” Wegener said.

The new Army initiative follows on the heels of a similar announcement in the UK. Recognizing the importance of preserving art and archaeology in times of conflict, the British Army created a Cultural Property Protection Unit last October.

In the US, the initial cohort of Cultural Heritage Preservation Officers will all be drawn from the existing Civil Affairs Divisions, so the Army isn’t about to go recruiting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—for now. “There are discussions,” said Wegener, “about a program involving direct commissions for candidates with the right education background and skill set who might want to join the military.”

The Smithsonian has spots for 25 experts in the March workshop. The program will be run out of at the Army Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command at North Carolina’s Fort Bragg, with the aim of deploying immediately afterward.