Op-Ed

Museums Must Adapt to Survive. There’s a Right and a Wrong Way

There's one key issue to keep in mind when museums talk about embracing new commercial endeavors.

There's one key issue to keep in mind when museums talk about embracing new commercial endeavors.

Natasha Degen

Museums are in a tough spot. They face internal challenges, like staff unionization, alongside mounting external pressures about what they should exhibit, who should serve on their boards, and whether they should repatriate contested objects. Operating costs continue to increase while philanthropic and government support decline. Public institutions no longer have a monopoly on the public display of art, but find themselves in competition with immersive art “experiences,” private museums, and museum-sized commercial galleries. Only a third of U.S. museums have met or surpassed their pre-pandemic attendance figures. Rarely has their model seemed more fragile.

Funding remains a top concern. Museums have struggled to reconcile the expectation that they remain free from commercial considerations with the reality that they rely on ticket sales, event rentals, and revenue from restaurants and retail. But now expectations are changing. The Museum of Modern Art’s director Glenn Lowry recently spoke approvingly of museums moving beyond the idea of their own sanctity and finding new income streams. The Art Newspaper has heralded “the dawn of the entrepreneurial museum.” More and more institutions are experimenting with creative approaches to earning revenue, leveraging their resources in bold and unexpected ways.

These ventures inevitably ruffle feathers, but there are reasons beyond the familiar pragmatic justifications why we shouldn’t reject them out of hand. A more open and entrepreneurial approach can advance—and, in the past, has advanced—museums’ essential missions.

The Museum of Modern Art’s founding director Alfred Barr once credited Saks Fifth Avenue with doing more to popularize modernism “than any two proselytizing critics.” As a fledgling museum, MoMA showed few qualms about mixing with commerce so long as it helped spread the modernist gospel. Its early design exhibitions traveled to commercial venues across the United States, including department stores, and featured catalogs with prices and checklists of manufacturers. Such initiatives not only addressed visitors as shoppers but aimed to affect manufacturing and consumption by seeding modernist aesthetics in the built and commercial environment.

A general view of atmosphere at MOMA Design Store on March 29, 2018 in New York City. (Photo by Andrew Toth/Getty Images for Surface Media)

In 1951 MoMA began renting and selling artworks through its Art Lending Service. By 1960 it sold $165,000 worth of fine art, or about $1.7 million today. A decade later—after “the endowment took a dive,” according to trustee Barbara Jakobson—MoMA created an Art Advisory Service for corporations. These services advanced the museum’s mission but also addressed needs the art world had yet to meet, rooting the museum more deeply in the broader art ecosystem. MoMA dissolved its Lending Service in 1982 and its Advisory Service in 1996. But the decision to wind them down seemed to respond to their redundancy rather than to reject commerce per se. Indeed, in 1989, amid these closures, MoMA launched its Design Store, where visitors buy limited-edition prints and design objects to this day.

Museums’ business ventures are most successful when they accomplish multiple things at once. The MoMA Design Store, for instance, promotes modern aesthetics, supports artists, and extends the reach of the museum’s brand. New Orleans’s Contemporary Arts Center struck a deal with a developer to renovate its building and turn its underused upper floors into an art-filled coworking space, establishing a significant revenue stream in annual rent and solidifying links to local creative professionals. In Pittsburgh, the Warhol Museum’s plan to build a concert venue on an existing parking lot intends to draw on Warhol’s legacy in film, music, and performance to bring visitors and money to the museum and the surrounding neighborhood alike. These museums have found ways to generate income, serve their missions, and raise their profiles all at the same time.

An interior view of the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing. (Photo by Mario Laporta/KONTROLAB/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Effective ventures leverage a museum’s expertise and assets without overtaxing them. Every item sold at the MoMA Design Store, for example, is vetted and approved by the museum’s curatorial team. This process sets the store’s offerings apart, while forging a direct connection to the museum’s primary activities. Leveraging existing expertise is also at the heart of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston’s public art consultancy and the UCCA Lab, a subsidiary of China’s Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, which facilitates collaborations with brands from China (Baidu and Huawei) and beyond (Budweiser and Airbnb). “It mobilizes the expertise we have developed—from lighting design to press-release writing,” UCCA director Philip Tinari has explained.

By monetizing their institutional competencies, these museums underscore the value intrinsic to the museum model. But not all museums advance their interests in such coherent ways. Others seem to regard their expertise and even their mission as a barrier to mainstream relevance. In an effort to attract broader audiences and secure their financial futures, they distance themselves from their core identity, undercutting what fundamentally makes them special.

Critic Rob Horning singles out the Indianapolis Museum of Art’s transformation into Newfields as a particularly egregious example of “saving” the museum by turning it into something else. In 2017, in addition to changing the museum’s name, its leadership took an aggressively populist approach, deemphasizing its encyclopedic art collection and adding Instagram-bait installations and crowd-pleasing attractions like a beer garden and mini golf course. “By recasting itself as not a repository of timeless values but a competitor in the experience economy,” Horning writes, Newfields surrendered “its own curatorial agenda, the traditional source of a museum’s authority, if not its reason for existing.”

Such reinventions raise the question: How far can a museum move toward entertainment before it is no longer a museum but something different?

Museums should be wary of any project or partnership, no matter how lucrative, that involves subordinating their mission to another agenda. Already many have felt the temptation to reorient programming toward the allure of popular entertainment and social-media virality.

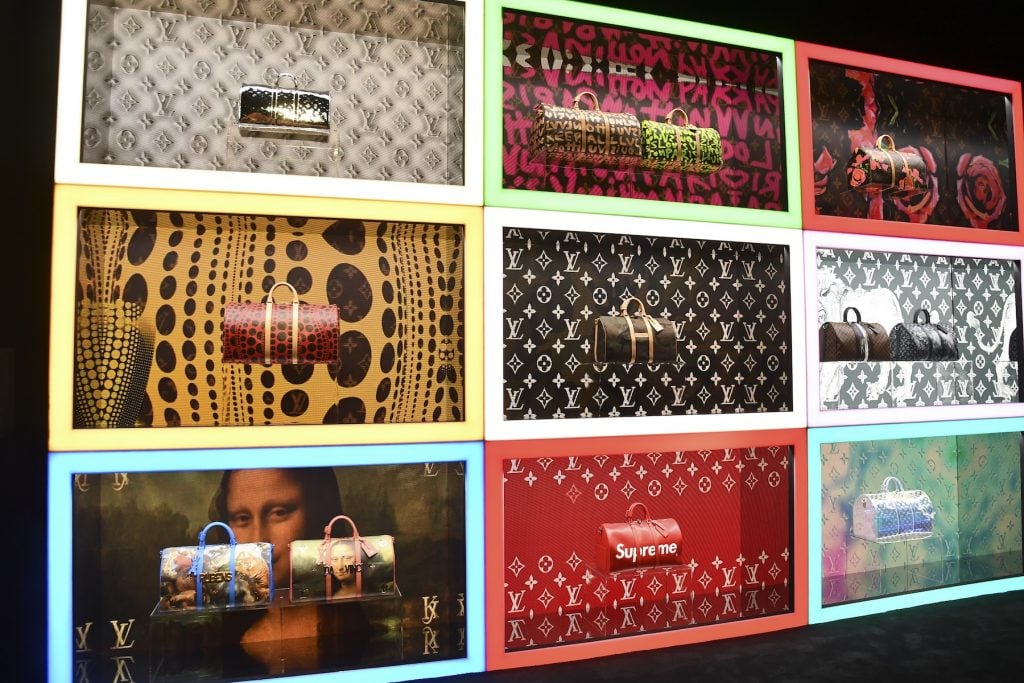

Opening of Louis Vuitton X Cocktail Party, Inside, Los Angeles. (Photo by Michael Buckner/WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images)

Some have opened themselves to “sponsored content.” In 2020 the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, for instance, displayed an Alex Prager installation that the artist originally created for a Miller Lite advertising campaign. Although the museum identified Miller Lite as a sponsor, it elided the beer company’s responsibility for the artwork’s very existence. Is this fundamentally different from a brand renting a space to host its own exhibition, as Louis Vuitton did the year prior just miles from LACMA? Profit-seeking ventures, from Dior to the Museum of Ice Cream, are eager to blur the lines between their offerings and real museums. Museums shouldn’t contribute to the confusion.

The challenge, then, is to learn from the commercial sphere without becoming captive to its values. In 2015, when Eli Broad opened his private museum in Los Angeles, he told me that his role model “was not another museum but what happens in an Apple store.” To create a more inviting environment, The Broad did away with typical museum fixtures, including the admissions desk and security guards, replacing them with visitor services associates present at the entrance to check in guests and scattered throughout the galleries, ready to speak about the works on view. A few years later the critic Michael Kimmelman noted that, setting foot in the newly reopened MoMA, “you may feel like you’re entering an Apple store.”

Visitors pass by the installation “hello again” by Haim Steinbach at newly-expanded Museum of Modern Art on the new 53rd Street lobby in New York City on October 17, 2019. (Photo by Kena Betancur/VIEWpress)

Museums want to look like Apple stores because their bright, immaculate spaces suggest perfect confidence in what they have to offer. (Apple stores themselves bear resemblance to the white cube gallery, though they eschew the gallery’s antiseptic and hermetic qualities with their natural materials and glass facades.) Their aesthetics are the architectural equivalent of a sans-serif typeface, which many museums have also adopted in recent years to seem more contemporary and less staid. For the same reasons, museums now refer to themselves using nicknames—The Broad, The Met, Mia—avoiding the antiquated connotations of the word “museum.” By embracing this informality, they hope to appear approachable and unpretentious, channeling the same logic as brands like Casper, Cora, Marcus, and Oscar. They exhort their audiences to address them on a first-name basis.

Museums can and should learn from business. They have been doing so for ages—gleaning new display techniques, for example, from department stores. But they shouldn’t lose sight of their unique character and place in society. There is a reason why for-profit enterprises, whether mega-galleries or luxury brands, often strive so hard to imitate museums and aspire to their meditative, restrained, hallowed air. They covet the museum’s special access to the public’s time and attention: its nature as a space to dwell in not merely for practical or utilitarian reasons.

In the attention economy, competition for our time and focus is fierce. Brands seduce us with ads that might engage us for a few seconds. They open lavish shopping destinations, even as we increasingly forgo in-person retail to shop online. To forge a more sustained connection, brands need to hold attention, and museums are among the very few spaces where we gather simply to be—to meet friends and talk, spend time with our children on a rainy day, wander around lost in thought. At a time when we live increasingly virtual lives, disconnected from immediate experience, the museum remains resolutely physical. We accept that museum-going involves patience and effort and, moreover, is deserving of it.

“The Seagram Murals,” by Mark Rothko at Tate Britain on October 15, 2020 in London, England. (Photo by John Phillips/Getty Images)

This is because, on a deep level, we understand that museums have a higher purpose. We are there not to change money for a good or an experience, but to change—to become, however subtly, slightly different in our conscious relationship to the world. To the extent that commerce can help sustain the museum without compromising its mission or values, we should see it as a resource. Commerce only becomes a threat when museums start to play by its rules.

Museums are public and communal spaces of an increasingly rare sort: places we gather with others in a civic, even quasi-devotional, capacity. Their main purpose is not entertainment. Today, too often, we mistake this for a weakness or liability and not the strength it is: a balm for our age of anxiety, spiritual longing, and loneliness. While the museum model must embrace innovation and change—now more than ever—its vitality ultimately springs from what it preserves and protects, that is, from remaining true to itself.