Opinion

How Artists Are Seizing the NFT Moment to Transform the Debate About Tech and the Environment

There is plenty to criticize in the world of NFTs—but artists are pushing forward important conversations.

There is plenty to criticize in the world of NFTs—but artists are pushing forward important conversations.

Charlotte Kent

Blockchain has been around for over a decade, actively disrupting the finance market. But it was only with its arrival in the art world that the conversation around its climate impact went truly mainstream. At any time, the finance industry could have suggested or demanded design changes. It didn’t. Artists did.

In December 2020, as the hype over digital art assets started to spread far and wide with million-dollar sales on Nifty Gateway and other platforms, the artist and computer scientist Memo Akten shared some research he had done on the energy consumption of minting NFTs. The website Cryptoart.wtf allowed people to check the energy of various art works—and the results were truly eye-opening.

If you look at the content of many recent NFTs, you can find ample evidence of ecological concern and consideration of technology’s impact among artists, from Penelope Umbrico’s Sunburn (screensaver) (sold on PostmastersBC) to Sara Ludy’s conceptual work, Plants are everywhere you can’t see them (sold on Feral File). Yet very few artistic gestures can hope to have the kind of real-world impact as Atken’s calculator: The site went viral, was mentioned in numerous news reports, and dramatically raised awareness about the ecological cost of NFTs, and by extension, of cryptocurrency.

Sarah Ludy, Plants are everywhere you can’t see them (2021).

At its core, the environmental impact is due to the currencies behind NFTs rather than digital artworks themselves: Bitcoin and Ether work on a principle called Proof of Work (PoW) in which computers solve complex puzzles to verify a transaction for which that computer or ‘miner’ is then rewarded with some amount of the cryptocurrency. Initially people could mine on a simple gaming computer, but the technology is designed to increase the difficulty of the puzzles as more people, or rather more computers, join the peer-to-peer network. This energy increase is an intentional part of the security in the system.

The Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance (CCAF) provides information on the energy consumption of Bitcoin every 24 hours with a variety of comparisons to try to understand what the numbers mean. How researchers arrive at these estimates is a space of much debate, and getting lost in the weeds can be a distraction from efforts to make change. The point is that energy demands are high, and that we live in an era when we need to reduce our carbon footprint across every area of our lives and insist that new technologies have that as a basic principle.

An alternative exists called Proof of Stake (PoS) and some altcoins have been using it for a while. PoS uses a pseudo-random process to assign a miner—now called a “forger” in this PoS landscape—the right to validate a block. The forger has to commit a stake in the chain. Tezos, a PoS cryptocurrency, has been around since 2018, but interest has risen recently, largely because of artists and art-and-tech designers committing to it for their projects. (Ethereum has been claiming it will shift to PoS for some time, and the increased demand for a better system has led to announcements to expect a shift this fall.)

Digital artists in particular have a chance to iterate in their explorations of climate and energy issues, to risk and fail and try again, as they attempt to both visualize and enact a better set of environmental politics. Recognizing that blockchain is a technology that won’t disappear, but remains an enterprise fraught with energy expenditures and lifestyle expectations, many artists concerned with its impact are seeking out better practices rather than abandoning the NFT space.

There is already a longer history of such artistic considerations to draw on, critique, and incorporate into the conversation. Back in 2017, Julian Oliver produced a media work and fully functional prototype for harnessing wind-energy to mine cryptocurrency, bringing the costs for miners down considerably. The proceeds from Harvest helped fund climate-change research, shifting the increasingly privatized power grid to a decentralized model. Commissioned by Konstmuseet i Skövde, the project showcases a more economically and energy considerate approach to blockchain.

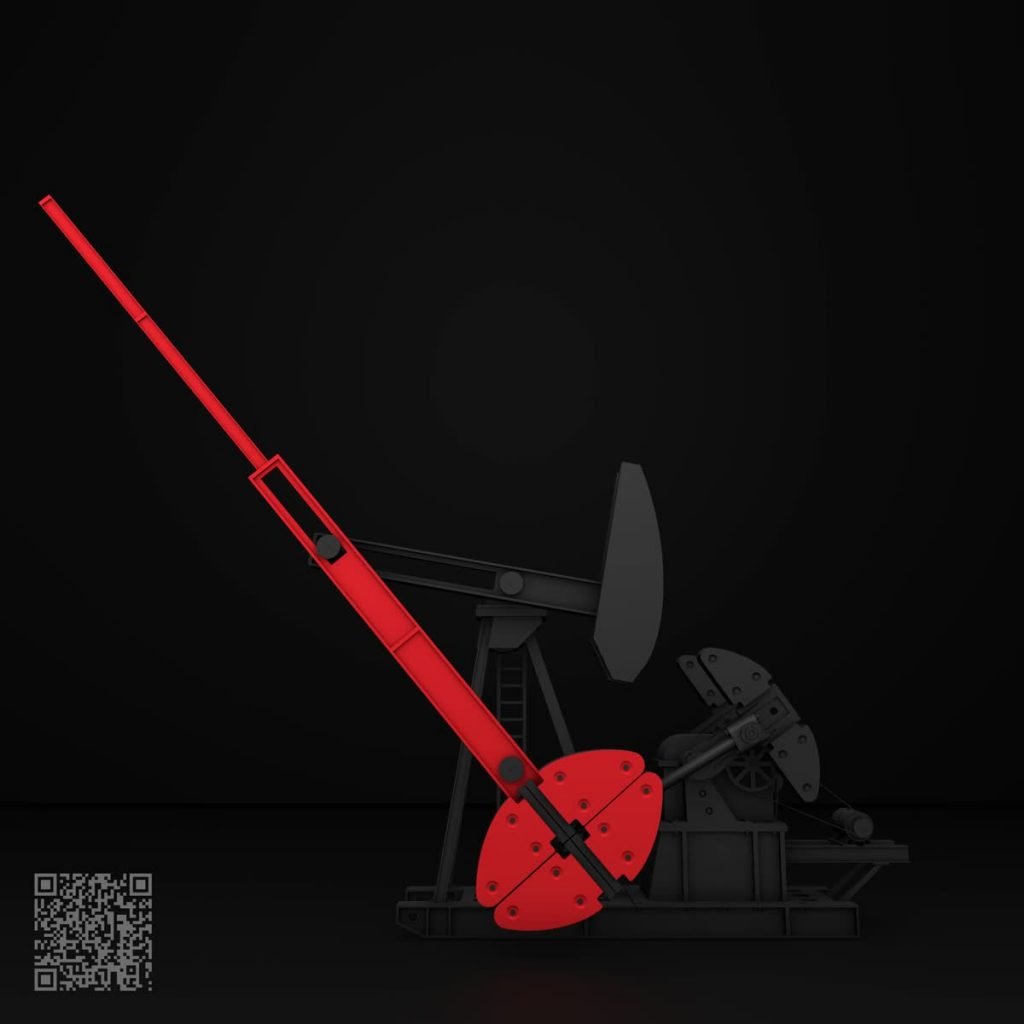

Still of Sven Eberwein’s animation Scarce Resources #01 — One Second of Petroleum (2021).

More recently, Sven Eberwein’s Scarce Resources #01 — One Second of Petroleum (2021) on Foundation, aims to reverse one second of global petroleum emissions. The NFT ties the money of its sale to the purchase of an appropriate amount of carbon offsets: 1,124 barrels of oil are burned every second, with 0.43 tons of carbon emissions emitted to the atmosphere per barrel, producing 484 tons of CO2. There is something awe-inspiring about how Eberwein’s gesture shows the scale of a problem, while also using an NFT to make concrete the investment that might be needed to make a difference.

Does it change the work’s meaning, though, that it runs on Foundation, and so remains linked to the wasteful and carbon-intensive PoW? Additionally, the listing for the work states that the “price of this work equals the cost of environmental damage occurring every second”—but how is that meaning changed by resales of the NFT? The current asking price would suggest a collector is attempting to flip Scarce Resources, odd since its price is supposed to be tied to its meaning. Such subtleties are important for future artist to consider.

Still from John Gerrard, Crystalline Work (Arctic)_15669184 (2021).

John Gerrard is probably most famous for his artwork Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas), a video featuring an animation of a flag made of black smoke, a comment on fossil fuels. His latest NFT work, Crystalline Work (Arctic), is a series of animation works each showing a robotic arm that selects and arranges virtual crystals, manipulating the mathematical structures of ice formation to create unique lattices (it’s inspired by one of the more bizarre proposals to save the planet: covering portions of the arctic in small silicon dioxide microspheres to reflect light—as if those glass particles would pose no impact to other species of the region). Each layout is cleared away and another begun, on the hour, running on Arctic time.

Sold on Binance NFT, which uses PoS, 50 percent of the proceeds support Regenerate.farm, a carbon sequestration farming group in Ireland, a nation committed to becoming truly green, both sustainable and organic. Gerrard’s project encourages us to move away from carbon offsets that many consumers and artists adopt, and towards more direct investments in green projects. The popularity of offsets belies their ineffective and even misleading approach to reducing our carbon impact.

(Rather than cultivating carbon offsetting by planting trees, the International Monetary Fund recently recommended saving the whales as a no-tech carbon sequestration practice. More whales would absorb more carbon when they eat phytoplankton, which contribute at least 50 percent of the oxygen to our atmosphere by capturing about 37 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide, so that “each great whale sequesters 33 tons of CO2 on average…. A tree, meanwhile, absorbs only up to 48 pounds of CO2 a year.” We certainly live in interesting times when the IMF considers saving the whales an innovative solution to our planetary crisis.)

Greenwashing is a real problem. We must be wary of platforms refusing to change their overall policies by pointing to the success of various artists’ individual eco-projects on their sites. When large organizations don’t change but insist on artists or collectors making the effort first, they skirt responsibility.

![Nancy Baker Cahill, Judicial [still] (2021).](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2021/05/nancy-baker-cahill-contract-killers.jpg)

Nancy Baker Cahill, Judicial [still] (2021).

I can’t fathom why any artist, collector, or gallery would refuse to adopt a less energy demanding currency amid constant news stories of the ecological and financial impact of global warming. (Alongside adopting more environmentally friendly web hosting services.)

The claim that many collectors are Ethereum- and Bitcoin-rich so platforms and people are obligated to produce for them, if they hope to succeed, seems flimsy. Those who are rich in these flagship currencies can certainly afford to stake into a new one (after all, if you are buying an NFT you are already trading some of the digital currency). Diversifying is in the spirit of the distributed ledger.

Artists today are using blockchain for myriad noble reasons—including the ability to automate funds to environmental, mental health, or social justice non-profits. But as science and technology present new developments, these projects won’t be perfect and can be refined. Artists are some of our greatest risk-takers and recent history shows that those working with technology are positioned to reveal the issues therein, even as the errors and shortcomings of their efforts need to be addressed. The important thing is that our critiques should aim to improve and encourage greater creativity in seeking more sustainable practices.

In March 2021, even as the giant prices for NFTs made them a part of the mainstream media conversation, Memo Akten took down Cryptoart.wtf because information about the carbon cost of NFTs was used maliciously, in classic instances of cyber-bullying. But he’s pressed on, aiming to establish a more productive type of conversation. In April of this year, he and others started providing resources on blockchain platforms in the Guide to EcoFriendly CryptoArt and a handy Google spreadsheet.

It took one carpet tile company thirty years to develop a carbon negative product. Every advance revealed additional improvements to adopt. For those of us looking to change our ways now, it must be a continuous effort of self-criticism, not one bound to the anxiety of our own inadequacy.