Opinion

An Art-World Philosopher Explains Why the Playboy Mansion Is a Cautionary Tale for the Work-From-Home Era + Two Other Interesting Reads

A weekly round-up of ideas from around the art web.

A weekly round-up of ideas from around the art web.

Ben Davis

Earlier this year, before the COVID-19 crisis changed everything, I had been trying to start a project of looking through the art web each week and picking out a few articles that were worth taking note of. The last few months have massively disrupted all kinds of routines, but I want to return to this small project. Now more than ever, writers are reexamining how art manifests in the world, and it’s worth keeping an eye on how those conversations are playing out.

Here are a few things that caught on the last week of April.

Paul B. Preciado, the philosopher well known in art circles as advisor to the recent Documenta, among other things, not so long ago reported movingly on his own experience with COVID-19 for Artforum. For the new issue of the magazine, Preciado returns with some lessons—albeit less from the experience of the virus itself than from philosophy.

Historically, rhetorics of containing mass infection, Preciado argues, tend to get caught up with ideology about what groups or people are desirable and undesirable, and to ratify existing social pathologies of their own. “Tell me how your community constructs its political sovereignty and I will tell you what forms your plagues will take and how you will confront them.”

Hugh Hefner’s famous rotating bed on display at the Christie’s Auction preview during the Playboy 50th Anniversary Party at the Palms Casino Resort September 20, 2003 in Las Vegas, Nevada. Photo by Bryan Haraway/Getty Images 2003.

Most notably, the philosopher reflects on the experience of compulsory “social distancing,” and how it accelerates types of social control that were already insinuating themselves into the life of affluent First World subjects. Drawing on past theorizing (in the book Pornotopia), he uses the bedroom in Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Mansion as a symbol of a lifestyle that has been long sold as a fantasy, collapsing bedroom, entertainment, and work into one seamless space—“a prison,” as Tom Wolfe wrote of Hefner’s work-from-bed routine, that was “as soft as an artichoke heart.”

Sunnier commentators might frame the technological tools that have allowed some parts of the white collar and media economy to keep ticking over as life-savers, maybe even prefiguring a less alienated form of office life. Those with jobs that can be done remotely get to be their own version of Hugh Hefner’s “horizontal worker” now, working in their pajamas and being fed an endless stream of entertainment (adult and otherwise) to keep them becalmed.

Preciado, however, wants to caution that the new virtual-work mainstream also fits more into a narrative of the increasing collapse of all aspects of life into one continuous, commodified, hyper-surveilled performance. The expedient new arrangements are likely to lead to new and insidious forms of control if not approached critically. (And obviously, as he points out as well, the sunnier narrative ignores all the “vertical workers” who can’t work from bed.)

“Governments are calling for confinement and telecommuting,” Preciado writes. “We know they are calling for de-collectivization and telecontrol.”

This is a big, intricate essay that ultimately makes a passionate case against isolation and for new forms of solidarity. I do have a question about how Preciado frames the COVID crisis. The keystone philosophical reference is Michel Foucault. As in Foucault, it’s not exactly clear where power is located in Preciado’s essay, with “regimes” of discourse just seeming to permeate everything omnipresently. The argumentation tends to proceed by the mechanism of homology—something like this: the rhetoric of trying to keep diseases out of the body is like the rhetoric of keeping immigrants out of a country; therefore the two are governed by the same discourse.

I’d put more stress on who amplifies what ideologies and whose interests they serve. Anti-immigrant regimes, for instance, have not risen just because of a general Western philosophical pathology that has constructed the ideal subject as “an immunized body, radically separated, that owed nothing to the community.” Very powerful political and corporate interests have long found it convenient to amplify xenophobic ideas to deflect from their own predations and create scapegoats for the grinding disparities an unfair economic system produces. A ready-to-hand example: Donald Trump is clearly hell bent on turning COVID-19 into “the Chinese virus” as a way to mask his own malign incompetence and to hold onto power.

Preciado arrives at advocating “a new sharing with other beings on the planet.” But he also says, towards the end, “[l]et us use the time and strength of confinement to study the tradition of struggle and resistance among racial and sexual minority cultures that have helped us survive until now.” Surely those traditions of struggle emphasize targeting specific levers of power as much as the importance of new ideas. ACT-UP, just as an example, was very concrete about locating power in the Reagan administration, the Koch administration, the FDA, the Catholic Church.

Artie Vierkant, Image Objects Installation View (2015). Image courtesy Perrotin.

In “The Image-Object Post-Internet,” written a decade ago, Vierkant wrote one of the closest things that came to count as a manifesto of recent years. “Post-internet art”—that is, art that blurs the lines between online life and in-gallery experience, or comments on that condition—is sort of relegated to historical object now, but it was a major force in art in the first half of the 2010s. With old structures of the art world now wobbling beneath the weight of lockdown and reliance on digital tools becoming even more pervasive, Vierkant returns to make the case that the “post-internet” trend’s underlying impulses were connected to the fallout from the 2008 Great Recession, as a questioning of the way art was presented in the “traditional” white cube and an attempt to find an available working alternative.

“It seems fitting that the twin collapse of finance and real estate coincided with a way of making art that reconsidered the dematerialization of the object and made a joke of the white cube,” he writes. An interesting argument, and thought-provoking when it comes to thinking of what may be emerging again now (though one to think about with all of Preciado’s cautions in the back of your mind.)

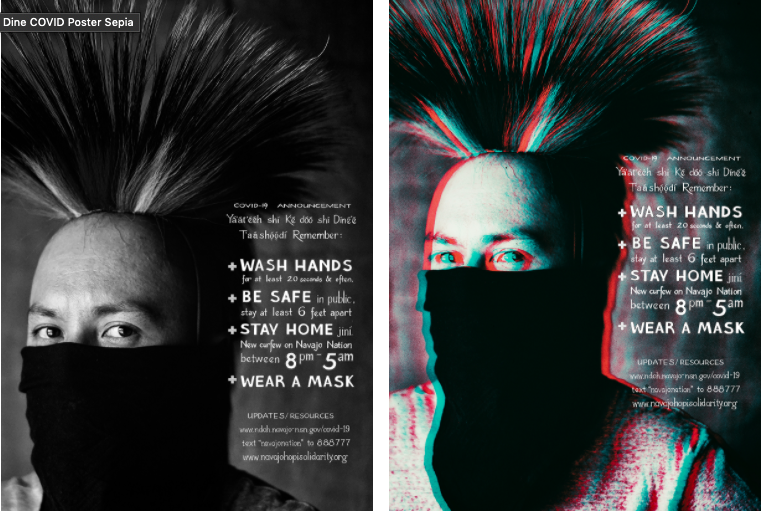

“Diné COVID PSA” by Chip Thomas.

Chip Thomas is an artist, activist, and physician who has been working on the Navajo nation since 1987, coordinating the Painted Desert Project, a mural-making initiative. Collaborating with grass dancer Ryan Pinto as a model, he’s created this graphic, which Art Journal brings to my attention. It’s being offered both as a practical resource and a way to focus minds on just how badly the Navajo Nation has been hit, enduring the third highest rate of infection in the country after New York and New Jersey.

The poster’s link takes you to a site, where anyone can donate to Diné and Hopi families who are dealing with the pandemic.