Opinion

How Paul Pfeiffer and Arthur Jafa Help Rethink the Ethics of Sharing Traumatic Imagery + Two Other Illuminating Reads From Around the Web

A weekly round-up of interesting and important readings from around the internet.

A weekly round-up of interesting and important readings from around the internet.

Ben Davis

Each week, countless articles, think pieces, columns, op-eds, features, and manifestos are published online—and any number cast new light on the world of art. Each Friday (when I can!), I pick out a few recent pieces that might inspire some larger discussion.

Ingram, a philosopher, art historian, and media theorist, dives into one of the most charged and consequential problems of the recent period in visual culture: how to relate ethically to the flood of images of unspeakable racist violence.

She writes: “Crystalized by the current moment is a paradox: These images, in their circulation, oscillate between being tools of activism that galvanize protests and being the means for neoliberal capitalism’s persistence as Black death is instrumentalized as a spectacle—evoking sympathy rather than empathy, solved by black squares rather than action.”

Thus, large numbers of white people, newly radicalized by exposure to the horrible images of George Floyd’s murder and seeking out practical advice on how to be anti-racist, will find many online guides that prominently tell them not to share those same images. Trying to find a way to navigate the contradictions, Ingram looks to thinkers like artist-theorist Aria Dean and visual studies philosopher WJT Mitchell, but also to artists Paul Pfeiffer and Arthur Jafa.

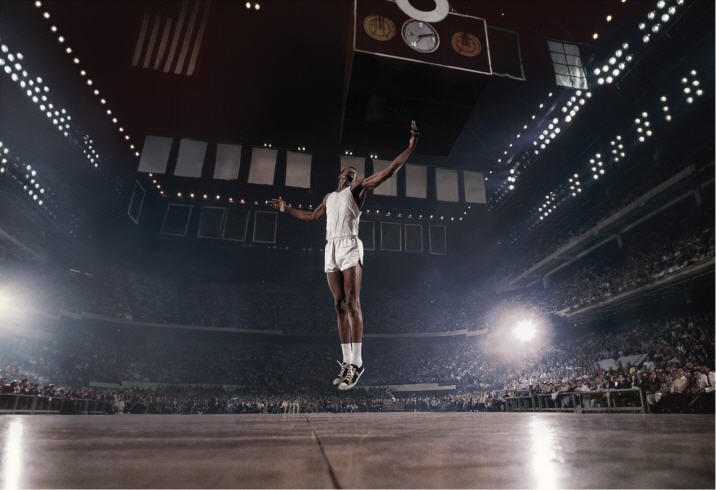

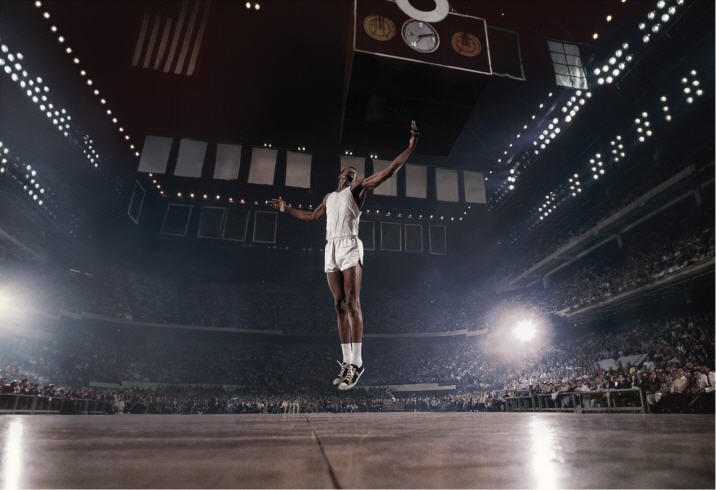

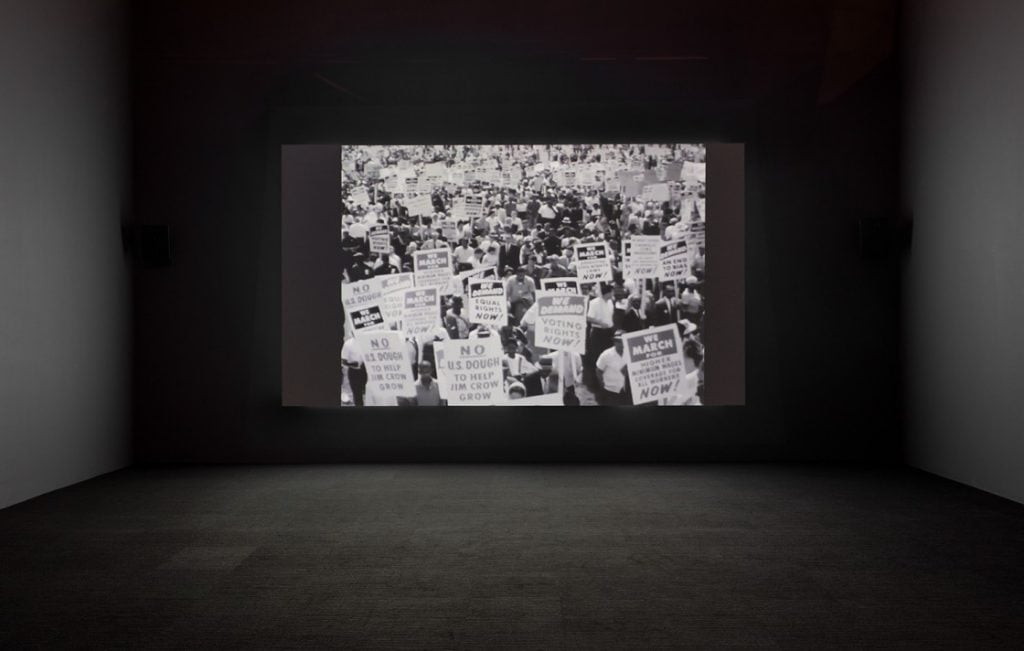

In their work, she finds a model of what she calls “contracirculation,” a sort of ethics of respect for the original context of an image even as it moves into new spaces. Moreover, she sees the video work of Pfeiffer and Jafa as helping to think about the connection between the cavalier treatment of images that alienate them from their context and the callousness that enables anti-Black violence in the first place.

Installation view of “Arthur Jafa: Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death,” at the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Brian Forrest.

Ingram ultimately argues that “in this current moment, the circulation of images like the Floyd video doesn’t merely commodify them into misplaced remedies for white guilt; it serves instead to build momentum to continue the movement.”

But what I think is so insightful about Ingram’s text is how she treats this contradiction as dynamic instead of static. She wants to point to the way the discourse is changing, how the debates around the seemingly insoluble contradiction have created new popular expectations around what such images demand: “The earlier critiques—that these images were retraumatizing, that circulating them could be an act of violence itself—have had a cumulative effect on how people understand and circulate images in general and the stakes involved, the commitments that should be implied, the ways to point them toward interpretations and actions.”

“Contracirculation” makes me realize that one of the reasons the recent revolt has been so widespread is not just because the specific acts of state violence have been so horrifying, or that these acts happen to have been caught on film, or even because their circulation happens to coincide with the world-shaking moment of a political, economic, and public health crisis—though of course these factors are key.

It seems likely that the reaction has been so very widespread also because so many people—particularly a younger cohort whose identities are substantially shaped by social media—have been previously exposed to intense, sustained online debate over what it means to see and circulate such images on social media during past waves of protest. These debates have left a mark and raised the stakes. For huge numbers of people, the need to do more than consume and share hyper-charged images has been a lesson they take into this new moment.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Ariel Goldberg, Camera Lesson (_2210485) (2018) Ariel Goldberg, Camera Lesson (2018). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

In a beautiful and personal essay, Robinson, a curator, writer, and editor-at-large for Atlanta-based art site Burnaway, also reflects on the recent circulation of images of racist brutality, and how they push her to go beyond a model of art production that “relies on Black suffering, or juxtaposes its joy against its absence” and toward models that suggest alternative relationships between photographer and the photographed. She finds the beginnings of an answer in Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s photo practice, where deliberately staged but intimate self-portraiture becomes a way to ask questions about agency to the viewer, about “where they see or don’t see their gaze landing when consuming the image.”

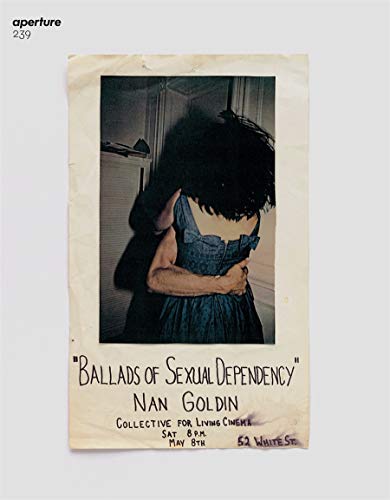

Aperture, Summer 2020.

From Aperture’s summer issue on the influence of Nan Goldin’s visual diary “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency,” Stoppard tracks the impact of its anguished, intimate chronicle of hard-times New York in the ‘80s on the look of fashion photography. In the process, she questions how an unposed, grungy “authenticity” has become the go-to virtue in the present commercial image economy, as it tries to wrestle with its audience’s increasing disgust with the commodified life and interface with the dissident energies shaking society. In the process, fashion turns authenticity into a pose, Stoppard argues, to the point that images that openly admit that they are staged in a studio might be more truly “authentic.”

And, at any rate, if the power of an unposed, de-glamorized look is what today’s photographers get from Goldin, they fail to look pack the surface—or rather to see that surface clearly:

The idea that artifice can be somehow truthful is central to understanding Goldin’s work. This is where her understanding of fashion is so interesting—she sees that the surface is central to our sense of self, to the process of being, to happiness, confidence, love, life itself. She takes stylization seriously; it’s obvious from her photographs of great looks, of performers and drag queens, of nights out dressed up, of makeup smeared and newly applied.