Politics

The Penn University Museum Is Working to Repatriate the Skulls of Enslaved Peoples in its Collection Following Student Protests

The skulls were collected by a discredited physician.

The skulls were collected by a discredited physician.

Taylor Dafoe

The Penn Museum at the University of Pennsylvania is putting in storage a collection of more than 1,000 skulls, including some that belonged to enslaved peoples, following an outcry from students.

The crania, which were held in a private classroom, belonged to the collection of Samuel George Morton, a 19th-century Philadelphia-based physician known for his “broadly white supremacist” views, according to the institution.

Last year, a group of students at the university discovered that 53 skulls in the Morton Cranial Collection came from individuals enslaved in Havana, Cuba, while two others belonged to enslaved Americans. They presented their findings at a symposium hosted by the Penn & Slavery Project, an initiative tasked with probing the school’s “historical connections with the institution of slavery.”

The museum, which reopened to the public today for the first time following a four-month shutdown, is currently working to repatriate or re-bury the crania, it said in a statement last week. In the meantime, the skulls will be moved to storage before the end of this week.

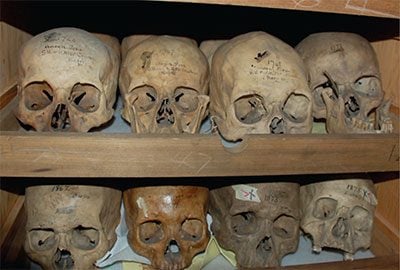

Skulls from the Morton Cranial Collection. Courtesy of the Penn Museum.

“Given that not much is known about these individuals other than that they came to Morton from Cuba, we are committed to working through this important process with heritage community stakeholders in an ethical and respectful manner,” the museum’s statement explained.

“This process is of enormous importance, but we’re just at the beginning,” a representative from the museum added in an email to Artnet News.

Once in storage, the collection of skulls will still be available to researchers, the representative confirmed, noting that the objects have been an important resource for studies in cerebral cortex shape in human evolution and patterns of trauma on the skull, among other topics.

As of now, none of the objects in the Morton Cranial Collection, which the museum acquired in 1966, are on public view.

A prominent member of the Philadelphia medical community during his life, Morton’s work has since been largely discredited by scientists for its baseless assumptions and poor documentation. He used his research to show that “Europeans, especially those of German and English ancestry, were intellectually, morally, and physically superior to all other races,” the museum’s website states.

Calls for the museum to restitute or rebury the skulls grew in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, as art institutions across the country and around the world have been pushed to reckon with systemic racism and the legacy of colonialism.

“We recognize that this museum was built on colonialism and racist narratives,” the institution said a separate statement following Floyd’s death. “We are working to change these narratives and the institutional biases that accompany them. Racism has no place in our museum. We must do more.”