Every Monday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, gazing into the art industry’s most conspicuous new void…

HOODWINKED

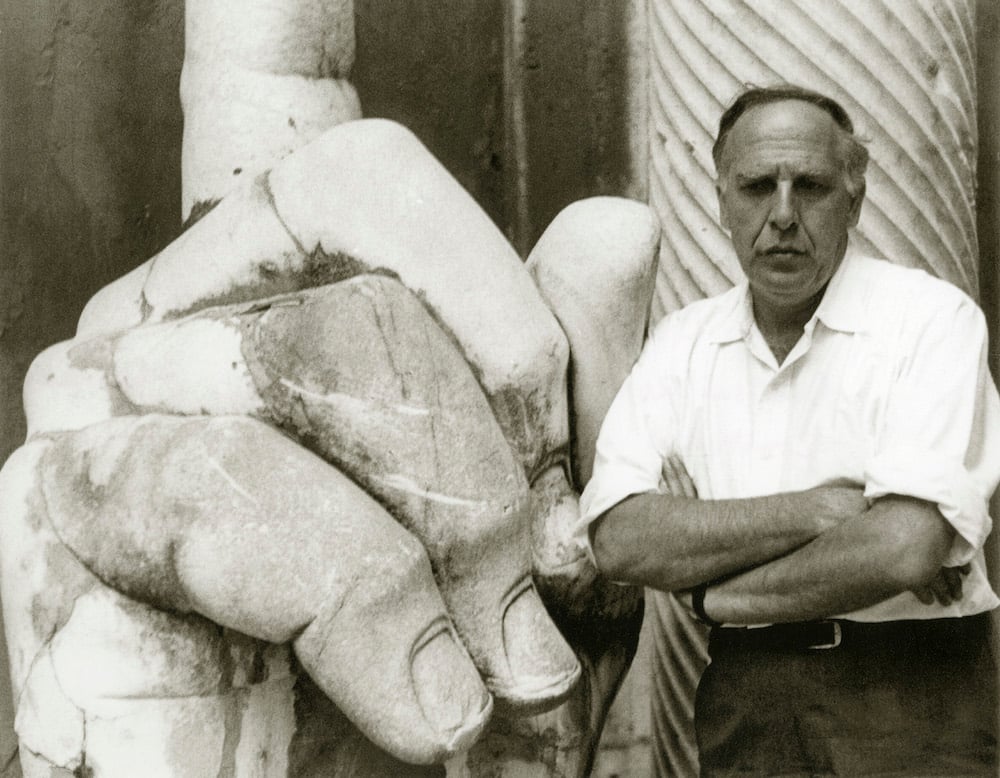

Last Monday, the National Gallery of Art, Tate Modern, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, quietly issued a joint press release announcing that “Philip Guston Now,” a touring retrospective previously postponed to July 2021 due to the coronavirus pandemic, would be delayed until 2024 so that “the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted.” But the museums’ purported good intentions are already backfiring, and the grim road I fear lies ahead raises fundamental questions about museums’ responsibilities in an era of radioactive politics and widespread social injustice.

A joint response from seven spokespeople representing the four institutions confirmed to Artnet News on Friday that at issue is the show’s inclusion of “approximately 25 paintings and drawings that Guston created depicting white-hooded figures that allude to the Ku Klux Klan.” This obviously explains the following sentence in the original statement: “The racial justice movement that started in the US and radiated to countries around the world, in addition to challenges of a global health crisis, have led us to pause.”

The seven representatives went on to tell Artnet News that the institutions would “bring in additional perspectives and voices to shape how we present Guston’s work at each venue,” and that this would be “a complex and layered process that goes beyond rewriting labels, but takes into consideration the ways in which we communicate the production of this work in its time and the reception by audiences today.”

For the uninitiated, there is nothing ambiguous about Guston’s intentions with the KKK works. His cartoonish renderings show the Klansmen in quiet, everyday moments—smoking cigars, driving, even painting at an easel—communicating the disturbing reality that their real-life counterparts have been living quietly among average Americans for the terrorist organization’s entire history. Guston wrote that he had been “haunted” by the Klan since he saw them violently assault striking workers as a child in Los Angeles. In a statement on Thursday condemning the decision to postpone the exhibition, Musa Mayer, Guston’s daughter and the leader of the Guston Foundation, wrote that the works “unveil white culpability… exposing the banality of evil and the systemic racism we are still struggling to confront today.”

Philip Guston, The Studio (1969) ©The Estate of Philip Guston. Private Collection. Photo Genevieve Hanson.

Just as important, the artist’s Klan-related imagery has enjoyed widespread art-world support for decades. Art historians and critics have been pummeling the postponement since last Thursday, from the University of Chicago’s Darby English in the New York Times, to Yale’s Robert Storr in The Art Newspaper, to one of Tate Modern’s own curators, Mark Godfrey, on Instagram. Noted Black American artists Glenn Ligon and Trenton Doyle Hancock, along with the Jewish American cartoonist Art Spiegelman, also contributed writing to the exhibition’s catalogue on the powerful impact of Guston’s KKK works.

Why did these institutions decide only last week that the 13 months ahead of the show’s opening were not enough to properly contextualize the works? They’re not saying. Storr alleged in his op-ed for TAN that the specific flashpoint was “pushback from [National Gallery] staff about an anti-lynching image from the 1930s.” When I asked about Storr’s claim, the museums’ representatives declined to comment. (Beyond the spokespeople, the lone defender of the delay so far is Darren Walker, the president of the Ford Foundation and a board member at the National Gallery, who told the Times the show would have appeared “tone deaf” without a rethink.)

The museum representatives also declined to answer other questions I put forth to elucidate what exactly happened here. Foremost among them was whether any concerns about the exhibition were raised by donors of either works in the show or funding critical to its presentation. Private collectors and corporate sponsors are just as aware of their vulnerabilities in this moment as museums, and their importance to presenting a major exhibition like this one is vital enough that threats to withhold resources could pressure the institutions to push back the debut.

But in the absence of answers, all that I can do at this point is speculate and search for comps. After doing both, a larger problem emerged: regardless of the real reasons for the postponement of “Philip Guston Now,” the four organizing museums have likely already doomed its legacy—and intensified the culture wars they were undoubtedly hoping to de-escalate.

Vincent Valdez, The City I (2015–16). Photo by Peter Molick, courtesy of the artist, David Shelton Gallery, and the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin, purchase through the generosity of Guillermo C. Nicolas and James C. Foster with additional support from Jeanne and Michael Klein and Ellen Susman.

“CITY” LIMITS

To contextualize the museums’ decision to delay, my colleagues in art media have primarily raised a trio of recent exhibitions that triggered overwhelming blowback for the institutions involved. However, I think there’s an even more instructive example worth discussing, and it’s not necessarily great news for the National Gallery and its partners.

In 2018, the Blanton Museum of Art unveiled Vincent Valdez’s The City I and The City II (2015–16), a monumental two-part painting series that depicted hooded Klan members, in Valdez’s words, “as regular people” who “get back into their cars, they go home, they put their kids to bed, they make lunches for the morning.”

Valdez and Guston have different backgrounds (the former identifies as Mexican American, whereas the latter was a white Canadian American), but Valdez’s comments prove they were vibrating at an eerily similar frequency:

I feel very strongly that America still finds itself trapped between the myth of who we think we were and the reality of who we really are. Americans excel at avoiding looking into a truthful mirror, because of what it might reveal. The “City” is that mirror.

The echoes don’t end there. According to the New York Times, the Blanton originally planned to install Valdez’s painting in 2017 but postponed its debut for a year to provide distance from the election of Donald Trump, as well as more time to hone the presentation in accordance with the tumultuous sociopolitical climate the piece would be entering as a result.

What did museum leadership use that extra year to do? The Times noted that the Blanton…

- built a special gallery with a sign warning that the work “may elicit strong emotions”

- installed a video showing an interview with Valdez about his work

- included six paragraphs of wall text that curator Veronica Roberts said she reworked “at least 400 times”

- socialized the paintings with the community by providing advance viewings to University of Texas faculty, students, and administrators

- consulted with more than 100 individuals and organizations, including the mayor, the Anti-Defamation League, and the Austin Justice Coalition

- beefed up personnel by adding six gallery “hosts” exclusively dedicated to fielding questions about Valdez’s work

- mandated that at least one of those hosts would be with the work “at all times” (along with a security guard)

- organized a three-month series of talks and programs to contextualize the piece

- launched a robust mini-website on The City aggregating much of the content above, along with bonus material such as additional reading and testimonials from community members

Guess what? It still wasn’t enough to make the painting completely fireproof. A “miscommunication among [museum] staff” meant the Blanton neglected to contact Austin’s chapter of the NAACP until the week prior to the paintings’ unveiling. After viewing the work, the chapter’s president knocked Valdez for not portraying Black lynching victims in the painting and implored the museum to “look outside [its] walls and figure out what’s going on in the community when you do these type of exhibitions.”

Similarly, the chairman of the University of Texas’s African and African Diaspora Studies told the Times that, after his experience with the work, he feared some people would interpret The City as a glorification of the Klan, highlighting “why there needs to be robust contextualization” about Valdez’s intentions.

On a personal level, my email archives also include an expletive-laced screed from a furious observer accusing me and my colleagues at Artnet News of bigotry for publishing the above-linked interview with Valdez about the painting. I’m sure the artist and the Blanton received worse.

So could the museum have done more? Technically, the answer is “yes.” But based on the list above, I also think it’s pretty damn hard to argue in good faith that the Blanton didn’t make an aggressive, thoughtful, multifaceted effort to address the challenge as best as it could.

This is my core problem with the additional postponement of “Philip Guston Now”: It is impossible to perfectly safeguard any artwork or idea from criticism. No matter how much time you take, you could always have done more. And this inconvenient truth is precisely what worries me so much about how this episode is now poised to play out in the culture sector.

US President Donald Trump holds up a Bible outside of St John’s Episcopal church across Lafayette Park in Washington, DC on June 1, 2020. Photo by Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images.

PREDESTINATION

In their original statement, the four museums mention that they have already been working on “Philip Guston Now” for five years. The original, coronavirus-induced postponement to July 2021 would have given them six total years of preparation, including 13 months after the murder of George Floyd. All told, the new 2024 opening date means they will ultimately have had roughly nine years to try to perfect the exhibition for the climate in which it will emerge.

But here’s the thing about “the moment”: by definition, it is constantly in flux. Who’s to say that events just as shocking to the status quo as those we experienced in early 2020 won’t thunder through the cultural landscape in early 2024?

The four-year postponement of “Philip Guston Now” doesn’t just feel extraordinarily long. It also feels extraordinarily loaded. Not much imagination is required to tie the show’s new opening date to the end of the next US presidential administration, particularly since the first host institution is located in the nation’s capital. But it’s anyone’s guess who will be in the White House at that point, let alone what they will have done (or not done) for racial justice during that term. A better future is not promised.

Given the culture wars we’re now enveloped in, I can’t help but think of one of general George Patton’s famous declarations: “a good plan violently executed now is better than a perfect plan executed next week.” And in the interim between “now” (or in this case, for July 2021) and “next week” (in this case, for 2024) lies the perhaps the most dangerous effect of all.

The saying goes that nature abhors a vacuum. Well, controversy adores one. Until “Philip Guston Now” premieres, it will exist as an ideological weapon that can be wielded with equal force from both sides of the political spectrum.

The right wing will portray the postponement as another example of “cancel culture” run amok, as further proof that the coastal elites running museums think the average citizen is too dumb to process nuance, and as more evidence of why American tax dollars should be siphoned away from the arts. Left-leaning observers will (continue to) portray the postponement as an act of institutional cowardice at a moment when uncomfortable ideas are more necessary than ever, as further proof that the paternalistic careerists running museums think the average citizen is too dumb to process nuance, and as more evidence that art museums need radical reform to serve their publics as intended.

Both sides now have three-plus years to build up their narrative of choice. This fact all but guarantees that the show is destined to suffer the fate the postponement was designed to prevent: being utterly defined by the roughly 25 works that allude to the KKK, based on viewpoints visitors had already forged in advance.

This is the same basic outcome suffered by the 2017 Whitney Biennial, which is effectively only remembered for the scandal surrounding the white artist Dana Schutz’s portrayal of mutilated Black teenager Emmett Till in her painting Open Casket. The stigma it left has amplified the reaction to every perceived misstep on equity or social justice the Whitney has made in the three years since, including the fury unleashed by the museum’s ill-conceived “Collective Actions” show last month.

The Open Casket dust-up is the first of those three earlier-mentioned precedents I’ve seen my colleagues in art media reference regarding the Guston delay. Yet the leadership there got off easier than the parties involved in the other two. The controversies surrounding the white artist Sam Durant’s Scaffold (2012) at the Walker Art Center in 2017, as well as the Afro-Latino artist Shaun Leonardo’s exhibition “The Breath of Empty Space” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland just this summer, each led to the resignation of the institution’s director.

The stakes can go higher than job security or institutional legacy, too. In 2017, the group exhibition “Art and China After 1989: The Theater of the World” provoked threats of physical violence against staff at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. The institution removed or worked with the artist to revise multiple pieces that triggered accusations of animal cruelty from activists. In this sense, I’d almost be more inclined to let you hide a live scorpion in my apartment than curate a major exhibition that incorporates images of the Klan, regardless of the artist’s well-documented intentions and the series’s overwhelmingly positive critical standing.

On one level, then, I sympathize with the organizers of the exhibition. But like it or not, the culture wars are back. And even if these four museums are not ready to engage yet, their inactivity will be used as ammunition by those who are.

[Statement | Artnet News]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: the surest way to get knocked out quickly is to behave as if no one is actually punching you.