Every Monday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, navigating cross-currents between labor disputes…

FALSE START

On Tuesday, concussive blowback from artists convinced the Whitney Museum of American Art to cancel an exhibition it had announced only the previous day. And while supporters and critics alike wrestle with the art-world implications of the institution’s latest controversy, I think we can better understand what’s happening by looking through the lens of an even bigger show of solidarity that shook up the world of professional sports the same week.

But first let’s set the stage. Planned to be on view at the Whitney from September 17 through year’s end, “Collective Actions: Artist Interventions in a Time of Change” would have included works produced to benefit causes related to the twin American crises in public-health and civil rights. Many of the pieces were created by emerging (at least, in the eyes of the white-cube establishment) artists who identify as Black or of color, and some were offered at steep discounts from market value with sales proceeds going entirely to nonprofit organizations or emergency fundraisers, not the creators.

According to some of the artists who spoke out against the show, the whiff of exploitation burbling up from the ingredients above only intensified based on the museum’s communication strategy. The same day the Whitney announced “Collective Action” to the public, it sent an email (tweeted in full by photographer Gioncarlo Valentine) notifying artists it had already bought their work through its Special Collections arm; would be including said work in the exhibition; and would compensate them for their unwitting contribution with an “Artist Lifetime Pass” allowing no-cost museum admission for two, “as well as other benefits.”

As Rahel Aima noted in The Art Newspaper, the Whitney’s collecting process here stood in stark contrast to that of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Both institutions acquired pieces from this summer’s Art for Philadelphia Bail Fund initiative—offered to the general public for just $300 each—“not only with the consent of participating artists but also at ‘institutional prices.’” In other words, the PMA and PAFA talked it over with creators first and agreed to pay a premium; the Whitney did neither.

The museum felt the repercussions immediately. In addition to Valentine, the chorus speaking out against the show included several more artists the museum intended to feature, such as Texas Isaiah, Kevin Claiborne, and the members of the See in Black collective (whose first print sale benefiting racial-justice organizations Valentine and Isaiah participated in). They were swiftly joined by a mass of sympathetic users not directly involved in the show but plenty pissed off by its details.

The Whitney publicly apologized and announced the show’s cancellation via Twitter on Tuesday. It also emailed the would-have-been-included artists a lengthier message offering a pledge to do better and an open line of communication to “talk more about the organization of the show and other concerns you have.” I hope whatever cables that line operates on are flame-retardant, because I’m pretty confident it has been channeling some thermonuclear-grade fire since Tuesday.

While this display of solidarity among artists dominated the conversation within the arts, it was only a prelude to the fireworks set off a day later among another highly specialized labor force: the players of the National Basketball Association. And there are more parallels between the two disputes than you might think.

The empty court left by the Milwaukee Bucks’ wildcat strike during what would have been game five of their Eastern Conference First Round series during the 2020 NBA Playoffs. (Photo by Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images)

WILDCAT FORMATION

On Wednesday, the Milwaukee Bucks, owners of the NBA’s best record and employer of back-to-back league Most Valuable Player Giannis Antetokounmpo, refused to take the court for a scheduled playoff game in the association’s (so-far) virus-proof “bubble” at Disney World. The team took this unexpected action to protest the seemingly never-ending riptide of American police violence against BIPOC, which claimed another victim on Monday when cops in Kenosha, Wisconsin shot unarmed Black father Jacob Blake seven times in the back as he tried to enter his car. (Blake survived but may be paralyzed for life.)

Within hours, the Bucks’ movement spread throughout pro-sports leagues across the US. First, the other five NBA teams with playoff games slated for that night made clear they would join the Bucks in sitting out. Then, players in the Women’s National Basketball Association, Major League Baseball, Major League Soccer, the National Hockey League, and rising American tennis star Naomi Osaka chose to do the same. The result essentially ground the US athletic machine to a halt in service of racial justice.

Management in the NBA and other leagues quickly attempted to co-opt the narrative by postponing the days’ games and matches, as well as couching the action in the softer terms of a “boycott.” But as writers like Briana Younger and Jacob Rosenberg noted, the only accurate label for the athletes’ collective action was a wildcat strike—the withholding of labor by a unionized workforce without the prior approval of union leaders.

Like so much else in 2020, it also represented a first. Although pledges to strike had been made at the university and professional levels in past years, no American sport had ever experienced an actual fast-twitch, in-season work stoppage over social causes before.

The action was effective in the NBA. During what would have been game time, the Bucks instead put together a Zoom call with Wisconsin’s lieutenant governor and attorney general asking for accountability and guidance on how best to use their position to bring justice in Blake’s case and the wider struggle against militarized, racist policing (my words, not theirs). After weighing the prospect of escalating the protest by ending the playoffs entirely, the league’s players ultimately voted on Thursday to return to play—but not without extracting a significant package of new commitments from the NBA and its 30 team governors (formerly known as “owners,” until the optics of a predominantly white group of businessmen “owning” a predominantly Black workforce became too grisly to bear).

Those commitments included working to convert all team-controlled arenas into polling places in this November’s general election; forming a new social-justice coalition of players, coaches, and governors to push for wider voting access, greater civic engagement, and “meaningful police and criminal-justice reform”; and the creation of new TV promos promoting these causes during the remainder of the playoffs. (At least seven NBA teams, including the Bucks, had confirmed their arenas would function as voting stations earlier this month.) And all of these moves arrive in addition to a concession won even before the wildcat strike: the establishment of a new NBA foundation to advance Black economic empowerment which will be funded to the tune of $300 million by the league’s 30 franchises over the next decade.

But while I see this entire saga as a testament to the power of righteous solidarity and an unqualified good for the country, there are many who see it as the latest malign development in a distressing trend in professional sports that needs to be turned back immediately for the good of the game (and the country). It is these retrograde reactions to the NBA’s wildcat strike that bring the Whitney’s canceled exhibition, and the larger art-world landscape, into greater focus.

The Whitney Museum of Art. Photo by Robert Alexander/Getty Images.

POWER MOVES

For the uninitiated, NBA die-hards—particularly those upset by recent trends—have often referred to the past 10 years (and counting) as the “player-empowerment era.” Their argument is that athletes have gained a historic amount of leverage in charting the course of their careers, especially when it comes to which teams they play for. Unhappy with management’s choices and your prospects for winning big where you are? Star players have proven capable of forcing their way to somewhere else even with multiple years left on their contracts with their current employers.

Another way to say this: after deciding that obedience to institutions was doing more to hold back their careers than advance them, laborers in a highly specialized industry have begun wielding the tools at their disposal to reclaim power over how and where they supply their work—and thus, who else gets to profit from it.

Sound like what’s been happening in any other industry you can think of?

I’m alluding to more than just the blow-up over “Collective Action” last week. Although the two timelines aren’t exactly parallel, the player-empowerment era has largely coincided with what I’d call the artist-empowerment era. The uprising against the Whitney’s would-be exhibition is only the latest manifestation of the trend.

In the past 10 to 15 years, in-demand contemporary artists have proven increasingly willing to hopscotch between big-name galleries on a show-by-show basis rather than sign with any one dealer long-term; to circumvent the traditional gallery system almost entirely for long stretches of their career; to build their own nonprofit and for-profit institutions from the ground up rather than rely on existing ones; and to amass audiences larger and more diverse than the traditional fine-art crowd from the beginning, including by signing with major entertainment agencies for non-gallery projects.

Why have we seen this surge for self-determination among artists? I would argue that it’s for some of the same reasons we’ve seen it in professional sports. True, NBA-specific financial arcana has been a critical factor in player empowerment, but the shift also originates from larger socioeconomic dynamics that artists have identified, too.

Contemporary art and professional basketball have both been ground zero for megaton explosions of capital this generation. Yet the talent pools in both industries have increasingly recognized they are receiving less of the surplus than the institutions that traditionally market and distribute their highly valuable labor. The reason is that these institutions do not necessarily operate with artists’ or players’ best interests in mind—a fact that plays out in everything from who gets institutional attention, to how talent is compensated, to what a career can be.

Technology has also served a crucial role in breaking open the old communication and distribution channels for the two workforces. Although some of the artists who blasted the Whitney for “Collective Action” online also gave interviews to mainstream media outlets like the New York Times and trade outlets like TAN and ARTnews, the dustup mainly took place across social media and email.

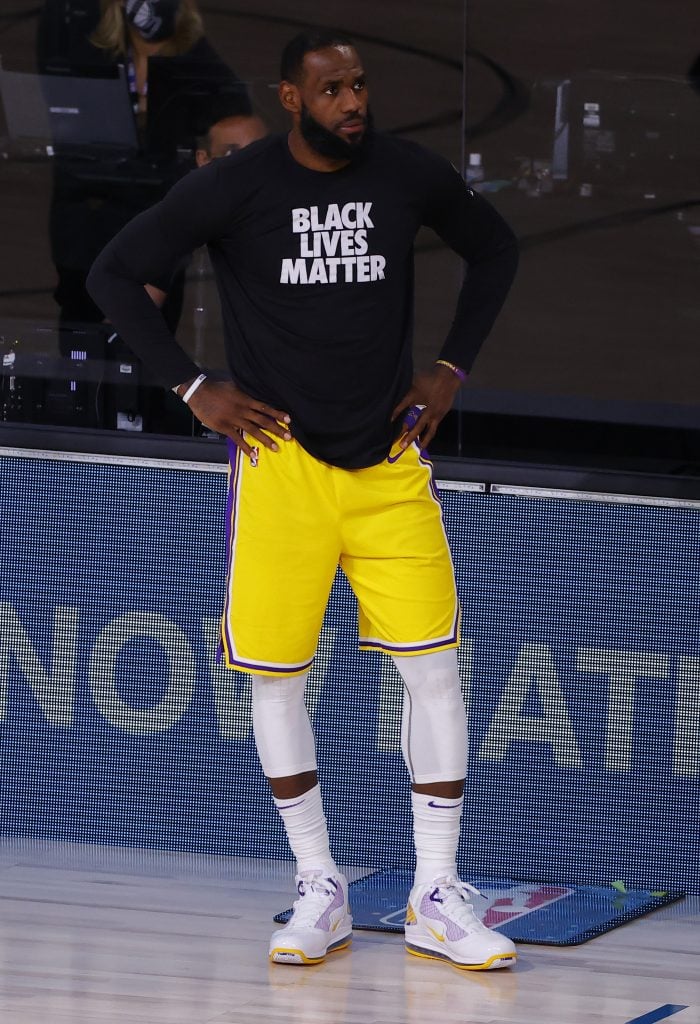

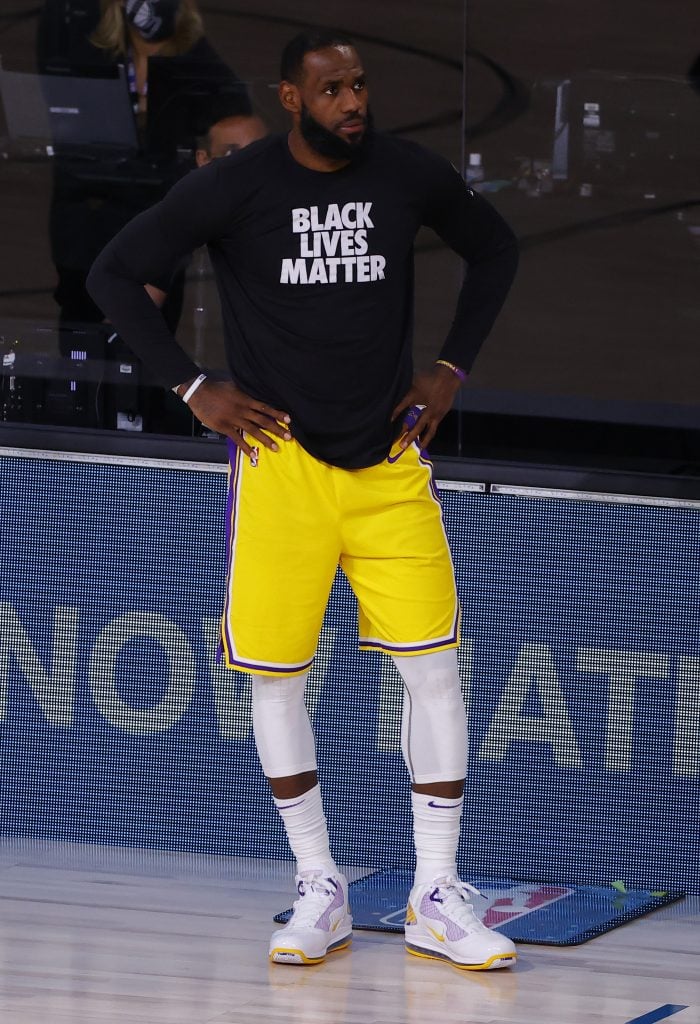

LeBron James waiting to check into a playoff game against the Portland Trail Blazers after NBA players voted to resume the season in the wake of their wildcat strike earlier the same week. (Photo by Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images)

Direct communication and direct sales between artists and their audiences have also been essential to the work of career-building in the arts this generation. Like traditional reportage, a traditional gallery or museum can certainly help amplify your message. But are these channels strictly necessary anymore? As suggested by some of the examples a few paragraphs up, more and more artists believe the answer is no.

If you don’t think pro athletes have reached the same conclusions, then you’re probably not aware of the prominent new wave of player-run channels like LeBron James’s Uninterrupted and the Players’ Tribune, let alone how much of traditional sports media has been reduced to discussing what athletes have already said straight to fans (and each other) on social media.

Finally, underlying these developments is a shared push for racial, gender, and social justice—not just in art and sports but in American life. In both the “Collective Actions” controversy and the athletes’ wildcat strike, it is not a coincidence that the institutions being challenged are overwhelmingly controlled by white men, and the labor forces pushing them are largely BIPOC. These longstanding imbalances in pro-sports and American museums have led to decades of professional frictions loaded with deeper significance, no matter how sincerely one side might try to argue that they’re “just business.”

The problem isn’t just what happened this time. It is that what happened this time already happened so many other times before, only with different details. The singular moment carries the weight of history, and past wrongs only resonate more powerfully in a time when the human toll of American injustice looms over every choice, every statistic, and every death.

Ultimately, this is why I understand the artists’ furious reactions to “Collective Actions.” It’s the same reason I supported the players’ wildcat strike, as well as why I was appalled when some idiot fans burned LeBron’s jersey and vandalized billboards with his image after he left my hometown Cleveland Cavaliers in 2010 in the player-empowerment era’s consensus origin point: If the old rules and norms only keep hurting you and people like you, what sense would it make to keep quietly observing them?

This is the playing field in contemporary art, pro sports, and life in general in 2020. (It wouldn’t be hard to rewrite this column to focus on shifts in electoral politics over the same epoch.) Lament the workforces’ methods if you want, but first recognize why those methods are in use—and most of all, that they are succeeding where others did not. Even if an institution only does so out of sheer ignorance or haste, making decisions without this full picture in mind runs the risk of catastrophe, and that won’t change anytime soon.

[Artnet News | ESPN]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: no game can exist without something to lose.