Imagine if Black jazz and blues musicians from the South had been excluded from the world of music because they didn’t receive formal training in conservatories and lacked representation in the entertainment industry. What would this historical omission have meant for American culture?

An omission not so different from this one has played out in the art world. There are 160 artists in the collection of Souls Grown Deep, the foundation which I serve as president. It supports the legacy of African American artists from the Southern United States. A few weeks ago, we launched the Resale Royalty Award Program (RRAP) to address the fact that, historically, many of these artists were bypassed by the art market, marginalized as a result of their race, gender, geography, and because they were “self-taught.”

Class, it turns out, is the largely unspoken feature of how the market operates—with gatekeepers across the art world relying on formal education as well as networks among established artists, critics, dealers, curators, and collectors. Of course, white artists who lacked formal art training—think Andrew Wyeth, for instance—managed to achieve unparalleled market success, just as countless Black, “self-taught” artists without these built-in networks did not.

A visitor looks at the “The Quilts of Gee’s Bend” exhibit at the Corcoran Gallery of Art 19 February, 2004, in Washington, DC.(STEPHEN JAFFE/AFP via Getty Images)

The artists in the Souls Grown Deep collection are based in the South and often come from rural areas, without easy access to the tight-knit, largely urban art-world networks. Nearly two-thirds of them are women, which, as Artnet News and In Other Words reported in a 2019 study, represent just two percent of the auction market. They also operated outside systems of wealth which may have overcome these boundaries of geography, gender, and race.

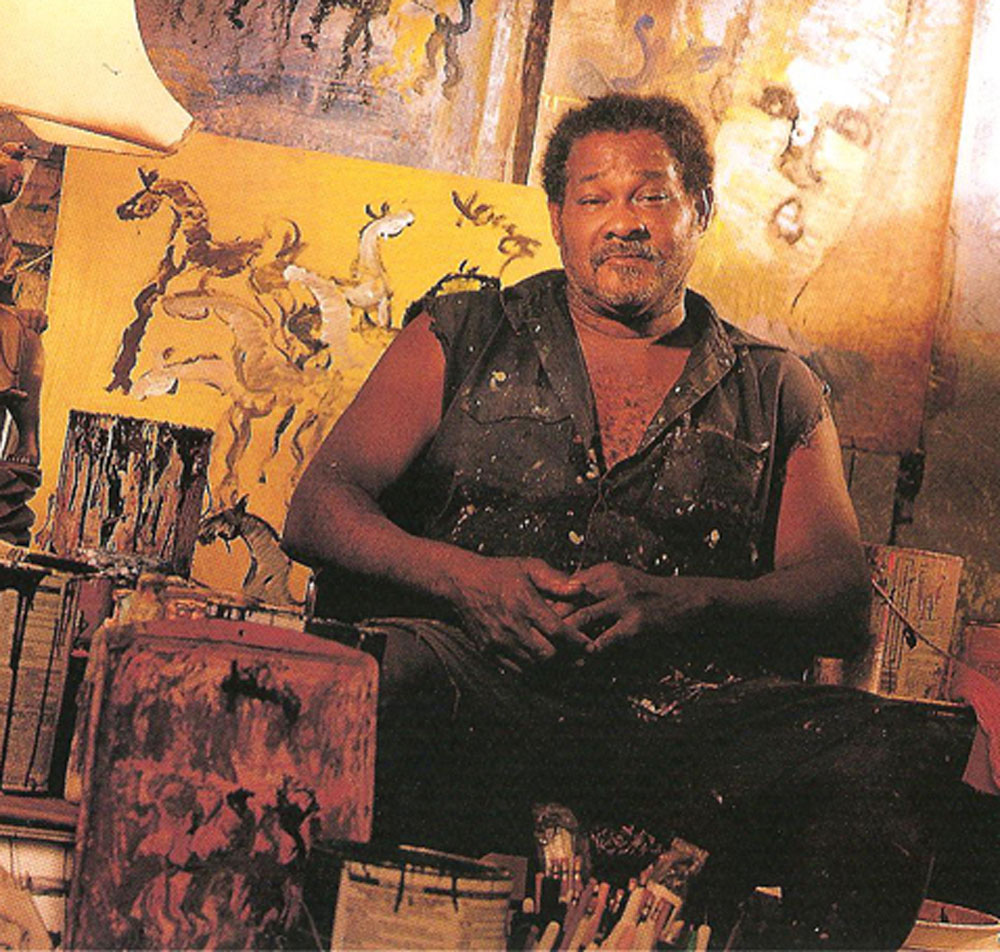

Despite these intersecting obstacles, the contributions of these artists—among them Mary Lee Bendolph, Thornton Dial, Ronald Lockett, Joe Minter, Lucy T. Pettway, Nellie Mae Rowe, and Purvis Young—became recognized for their creativity and significance over time. The artists’ gain in reputation has resulted in increased artwork valuations, creating an opportunity to rectify this injustice in the current art market.

Racial diversity in art collections is in the forefront of the art world’s consciousness. Museums, commercial galleries, auction houses, and private collectors are all pursuing relevance by evincing interest in works by Black artists. But the artists under consideration tend to be confined to a small list. According to a 2018 Artnet News and In Other Words survey, only 11 African American artists had cumulative auction sales exceeding $1 million over the previous decade. Why so few? The market follows a narrow set of parameters, which continue to exclude people of color who lack MFAs, gallery representation, art-world networks, or other attributes of class.

True equity will not limit acquisitions to the dozen or so Black artists who have achieved huge success in the art market to date. Collectors and collecting institutions can and should support artists who lack or lacked the class-based benefits of education and visibility in the art world but still made substantial contributions to art history. There is one simple way to do this: resale royalties.

Lonnie B. Holley, Protecting Myself the Best I Can (Weapons by the Door) (1994). © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society(ARS), New York. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio.

In more than 70 nations, artists are entitled to resale royalties—a percentage of the proceeds when their work is resold—although no such provision exists under US law. Musicians, authors, actors, and other creatives receive such royalties and residuals, and while visual artists receive compensation for commercial reproduction of their works, there is no structure which offers them financial return when their works are resold, often at exponentially higher values than their original sales.

Even without US law prescribing such royalties, organizations can elect to participate in this model. They just have to decide it’s a priority. That is why Souls Grown Deep recently launched the Resale Royalty Award Program—the most comprehensive such program in the US, designed to address systemic economic inequities faced by African American artists.

The awards are funded by sales of artworks, and will annually recognize each living artist in our collection with an award equal to five percent—the highest royalty threshold worldwide—of the proceeds received from artwork resales, up to $85,000 annually per artist. The program is issuing financial awards as of this writing, and it extends to past resales of works from the collection as well. The awards’ impact will be felt well into the future, since the foundation still holds three-quarters of its original collection, which it will continue to disperse strategically.

The auction of Kerry James Marshall’s Past Times. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

There remain some 50 living artists represented in our collection who may receive awards from this program—but there are countless other artists across the United States who could benefit from comparable programs adopted by peer organizations, auction houses, and even individual collectors.

Just a couple of years ago, the music producer and art collector Kasseem Dean (Swizz Beatz) argued for such a program, proposing that collectors selling works on the secondary market indicate that they want a percentage of the sale’s profits to go to the artist. The adoption of additional resale royalty award programs would call attention to the anomalous treatment of visual artists under United States copyright law—and can take a small step towards remediating race- and class-based inequities.

Reparations is a recurring topic in the United States. And a universally applied artist resale right would certainly do more to remediate inequities among artists and their heirs. Souls Grown Deep has long supported the ART Act, introduced by Congressman Jerrold Nadler (D-NY), each year since 2011. But extending benefits to artists does not have to wait for legislation. We can start now.

Maxwell L. Anderson is President of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation and Community Partnership.