This story is a collaboration between artnet News and In Other Words.

First came the furor. A recent flurry of high-profile market activity surrounding work by African American artists has been taken by many observers as a sign that—finally—history is in the process of being corrected. So far this year, six of the 10 most expensive contemporary works to sell at auction have been by African American artists. This is just one in a recent string of notable statistics, from the historic $110.5 million sum that Japanese entrepreneur Yusaku Maezawa spent on Basquiat’s punchy 1982 painting of a skull to the $21.1 million record price paid by the rapper and businessman Sean Combs, aka Diddy, this past May for Kerry James Marshall’s Past Times (1997).

All of this seems promising for an area of art history so woefully underappreciated and undervalued. But pan out and the broader numbers tell a different story, according to a joint investigation by artnet News and In Other Words. Around $2.2 billion has been spent on work by African American artists at auction over the past 10 years—a mere 1.2 percent of the global auction market during the same period, which was $180 billion, according to the artnet Price Database.

The popular perception that Wall Street has been rushing in to scoop up the work of African American artists has been framed by such high-profile sales as the Basquiat and Marshall records and the sense that there has been an increasing number of marquee museum exhibitions dedicated to African American artists. These landmark moments are “events of symbolic import, and those events then filter how we even look at reality,” says Hamza Walker, the director of the Los Angeles-based nonprofit art space LAXART. “But the symbolic can be mistaken for real.”

Auctioneer Oliver Barker at Sotheby’s May 2018 Auction with Kerry James Marshall’s Past Times (1997). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

A Top-Heavy Market

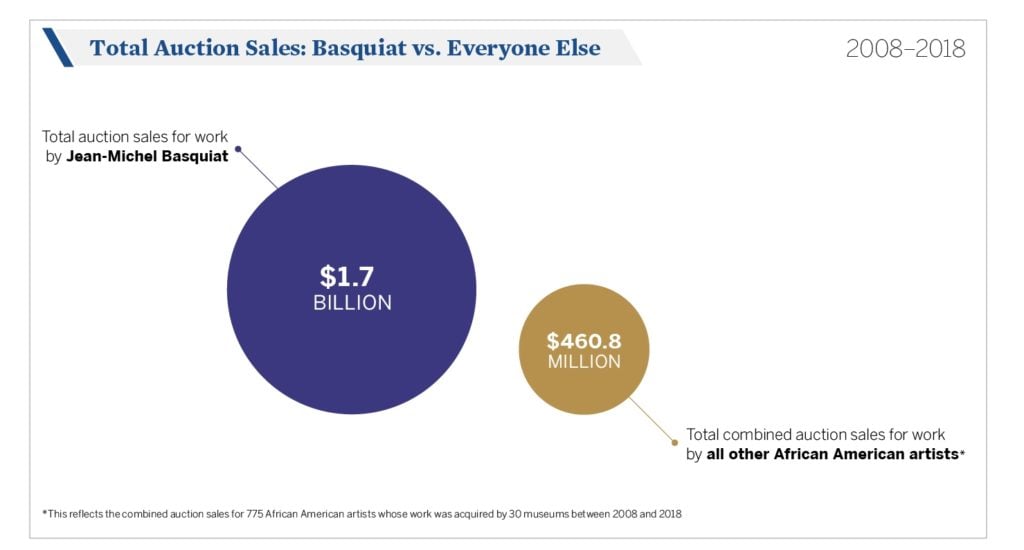

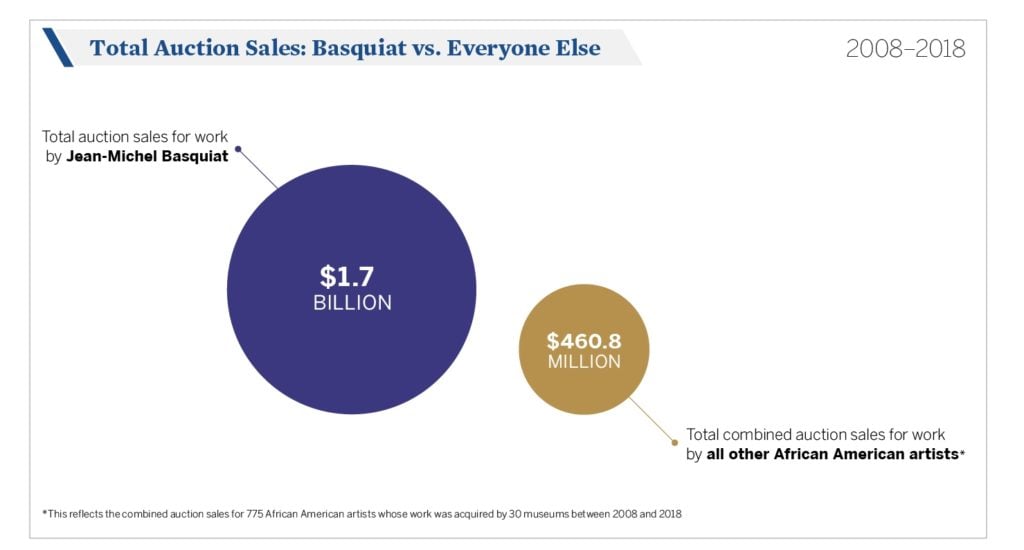

A more detailed look reveals an unbalanced market that is much smaller in both value and volume than headlines suggest. Auction sales of work by Jean-Michel Basquiat account for $1.7 billion of the $2.2 billion total spend—a staggering 77 percent—representing the big head (or skull, more fittingly) atop an otherwise meagre body. Of the six contemporary works by African American artists in the top 10 sold so far this year, four are by Basquiat. Indeed, 2018 marks the first time ever that African Americans other than the late young painter have made the list.

Image courtesy In Other Words at Art Agency, Partners.

Exclude Basquiat, and the total combined auction value of work by African American artists is $460.8 million—just 0.26 percent of the global auction market. For context, consider that more money has been spent at auction during certain single evening sales of postwar and contemporary art in New York than on work by African American artists over the past 10 years.

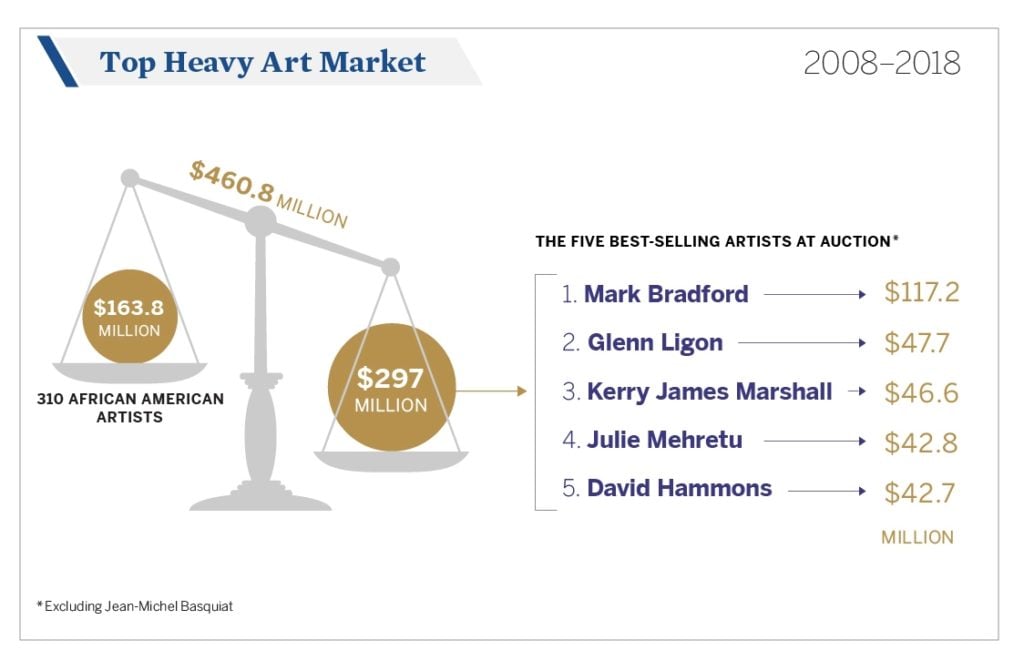

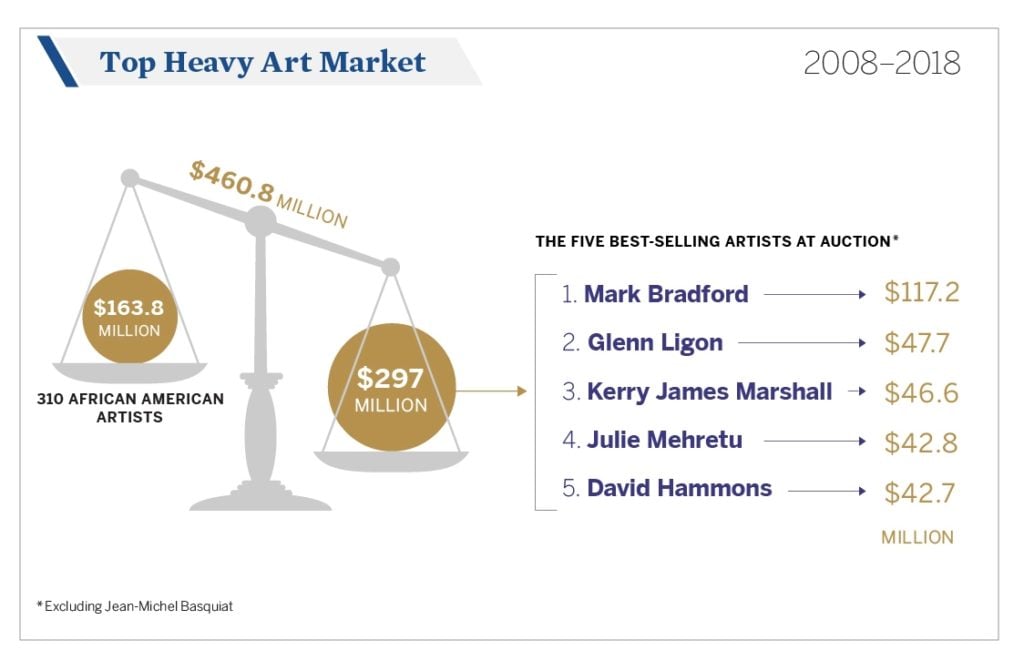

The market is top-heavy, even without Basquiat, consolidating around just five artists: Mark Bradford, Glenn Ligon, Kerry James Marshall, Julie Mehretu, and David Hammons, all of whose combined auction sales over the past decade account for $297 million—or 64 percent—of the $460.8 million total spend. Bradford is far and away in a league of his own: sales of his work account for 25 percent ($117.2 million) of the total. These top five aside, only two artists—Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Sam Gilliam—have generated auction sales of more than $10 million since 2008.

None of those seven markets is a fluke. “Each of those artists is considered a contemporary master,” says Jack Shainman, whose gallery represents Marshall, together with David Zwirner. “They have been really well celebrated in terms of the market, and these results substantiate them as major players.” Nevertheless, the “sharp wedge” of their success relative to other African American artists “is shocking,” he says.

Image courtesy In Other Words at Art Agency, Partners.

For these few contemporary giants, demand outstrips supply. Were a major work by David Hammons to come to market, for example, it would likely achieve a record price. A similar squeeze on supply characterizes the market for Marshall, an artist with limited production but an extensive waiting list. Since museums and leading private collectors get first pick, frustrated buyers further down the pecking order tend to battle for work when it comes to auction, driving prices up.

Of course, this bifurcation is also a symptom of market-driven trophy hunting. Many historically significant artists are overlooked by buyers who instead focus on the competition to acquire material by a small handful of figures. Work by certain artists is “becoming a commodity now, which is unfortunate—though the artists deserve all the attention they are getting and more,” says Jumaane N’Namdi, the director of N’Namdi Contemporary, who followed his father into the gallery business. “I get cold calls from investors: it is poaching season for African American art.”

Newfound Attention

The market heat is recent: 25 percent of the entire 10-year total was realized in the first six months of this year. Focused on a handful of artists, this spending has had a tremendous but narrow impact: for example, Bradford’s combined auction sales between 2008 and 2017 jumped 60 percent this year, while Marshall’s leapt from $13.2 million to $46.6 million.

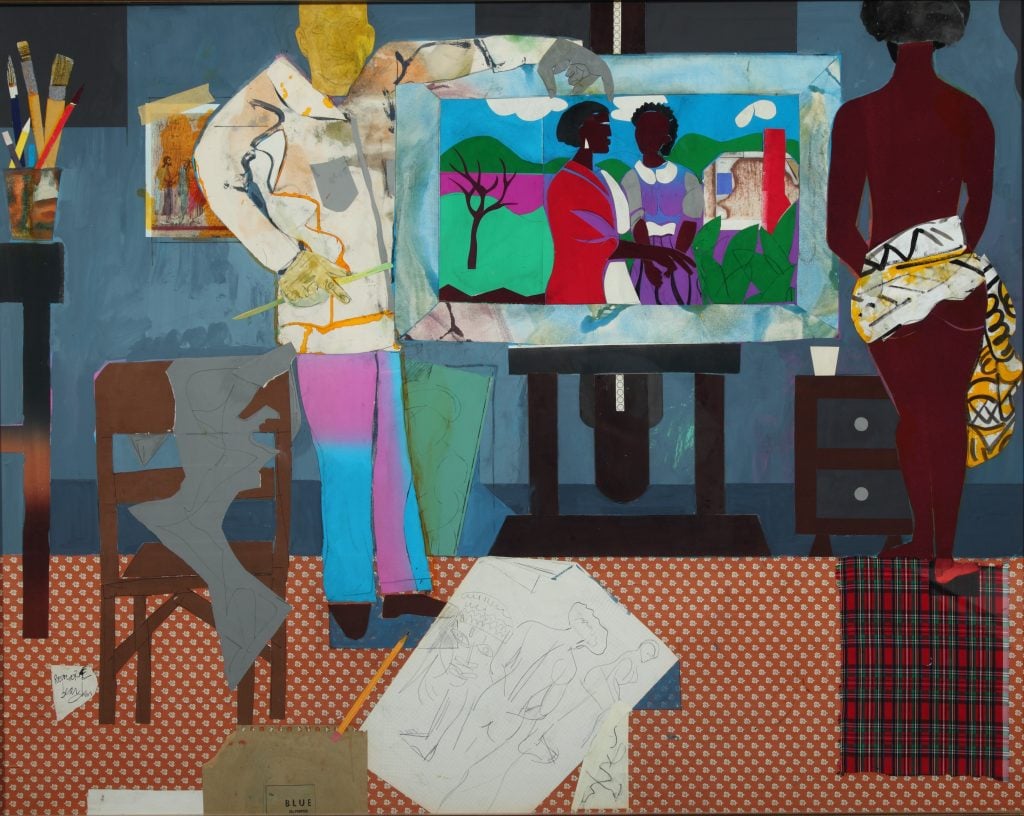

When the specialist auction house Swann staged its first dedicated sale of African American art 11 years ago, the numbers “were a lot smaller—and the pool [of buyers] was even smaller,” says Nigel Freeman, the firm’s director of African American art. For years, there were only four artists whose work would sell for more than $100,000, two of them born in the 19th century and two in the 20th century: Henry Ossawa Tanner, Robert Duncanson, Romare Bearden, and Jacob Lawrence. “It became almost a running joke that there were only two African American Modernists,” Freeman says of Bearden and Lawrence, “because that was all you’d see.”

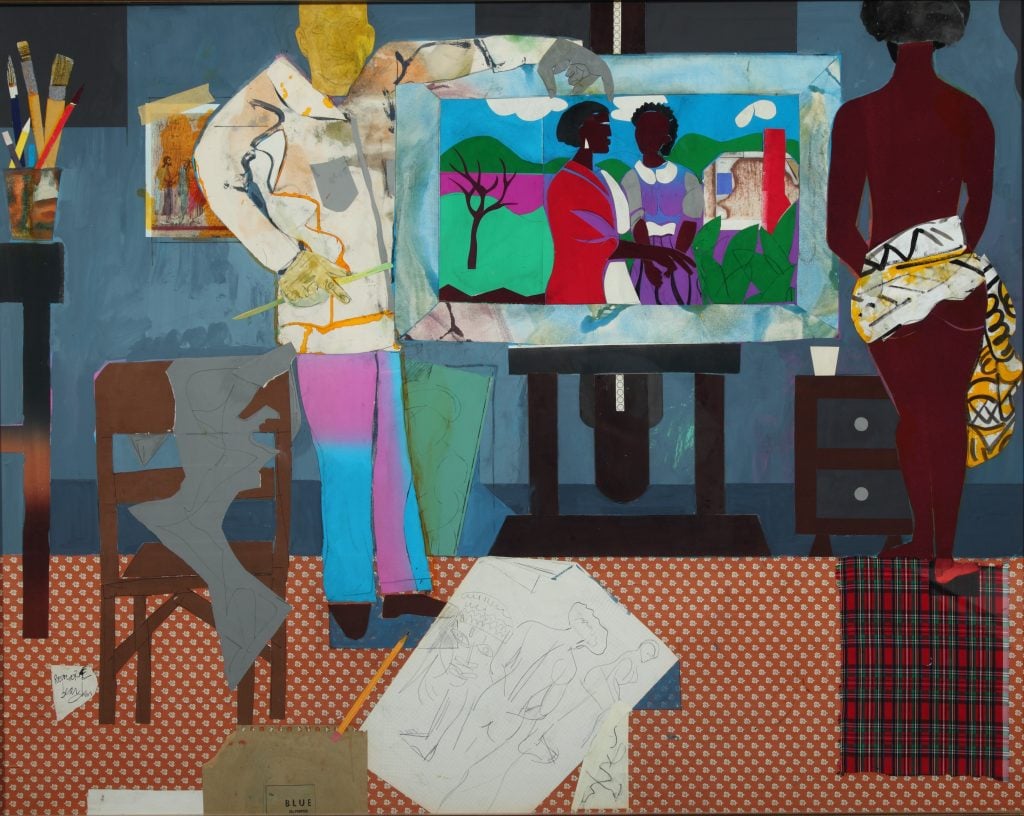

Romare Bearden, Profile/Part II, The Thirties: Artist With Painting and Model (1981). Courtesy of the High Museum of Art.

Over the past two years, the market has grown considerably (Swann’s dedicated spring sale in April, which made $4.5 million, was its highest-grossing to date in any category) and the pool of buyers has deepened, too. “People who collect Color Field painting or postwar abstraction are looking at Sam Gilliam,” Freeman notes, while “New York School collectors are looking for Norman Lewis.”

The Modern market is growing, but the contemporary is quickly outpacing it. Today, some younger artists already have secondary markets of equivalent size to artists of an earlier generation. For example, 46-year-old Wangechi Mutu and Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) have both had aggregate auction sales of $5.2 million over the past decade, while 92-year-old Betye Saar has a secondary market roughly equivalent to that of 44-year-old Trenton Doyle Hancock ($147,000).

Wangechi Mutu, Water Woman (2017). Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

This focus on younger artists is typical of many nascent markets, which “start with the art of the present day and when they mature inevitably look back in time,” says Allan Schwartzman, co-founder of Art Agency, Partners.

For many Modern artists, the seeming dearth of big prices is simply a matter of having been paid little heed for so long, and so recently “discovered” by the market and mainstream museums. Yet for some of the most recognized Modern artists, it is about supply: just try finding a great Jacob Lawrence for sale. If a major work by a Modern legend such as Alma Thomas or Romare Bearden were to appear at auction, “I suspect it would sell for numbers that would stun most auction buyers—who right now probably couldn’t describe a work by either artist,” Schwartzman says.

Contemporary Bias

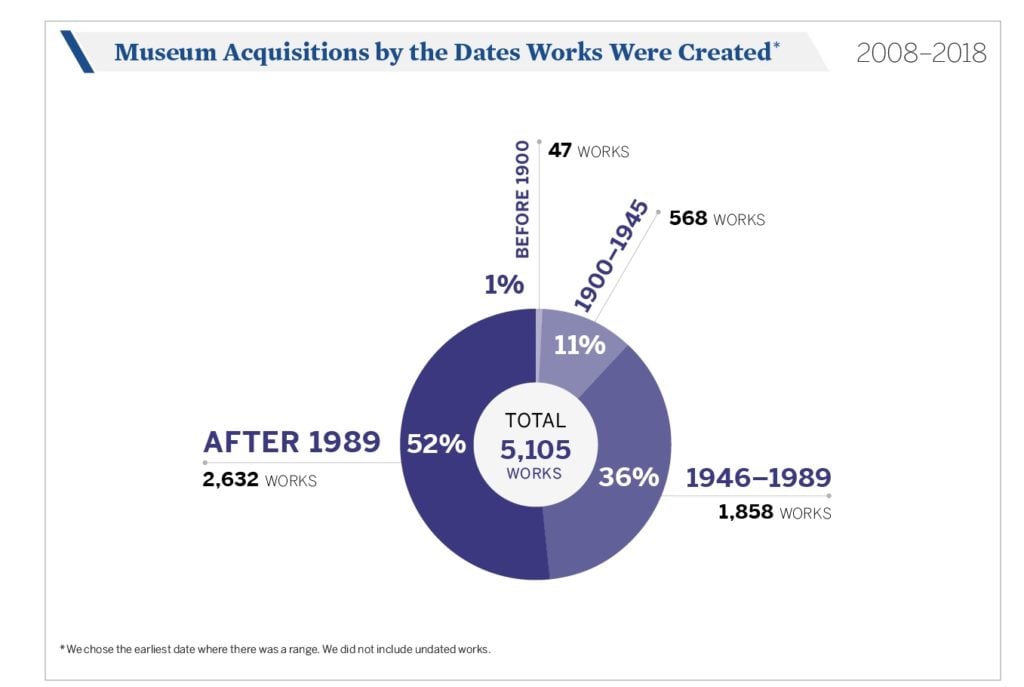

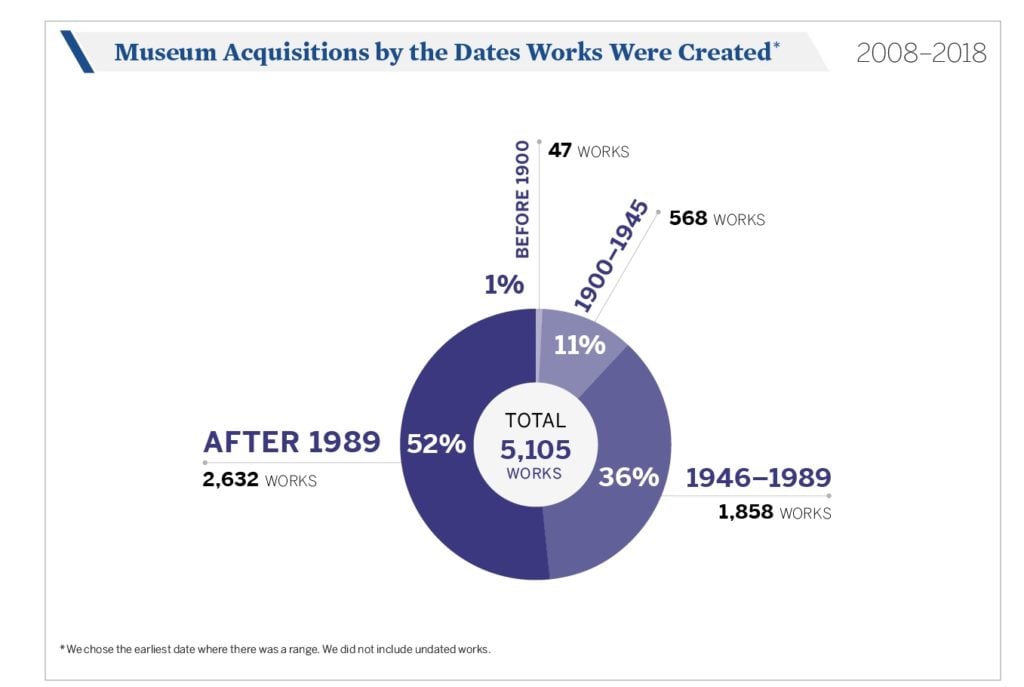

While curators are looking both forwards and backwards in history for acquisitions and exhibitions, their museums may not be able to afford to acquire Modern work. Our data shows a similar slant toward contemporary art at institutions: of the 5,466 works by African American artists that have entered the permanent collections of the 30 museums we surveyed, almost half—48 percent—were created after 1989. “Let’s just be honest—museums have a hard time competing with private collectors,” says Naomi Beckwith, senior curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.

The interests of patrons and collectors also inform what we see in both museums and the auction room. “The market still prizes younger and mid-career artists,” says Christopher Bedford, the director of the Baltimore Museum of Art, so “institutions have an easier time raising the money to bring works by younger and mid-career artists into the collection.”

Image courtesy In Other Words at Art Agency, Partners.

Looking Ahead

A critical dynamic defining the field is the effort being made by artists themselves to draw attention to their predecessors and peers. A generation of artists who are experiencing success in a professional gallery system and international art world that did not exist 50 years ago (and which, once it came into being, remained closed to many African American artists for decades) is deliberately directing the spotlight backward in history to significant artists of an older generation, as well as forward to a younger generation.

Think of Kerry James Marshall’s generous and moving homage in the Paris Review to Charles White earlier this year, on the occasion of a major touring exhibition of work by his mentor and idol: “I saw in his example the way to greatness. And because he looked like my uncles and my neighbors, his achievements seemed within my reach.”

Or consider the transatlantic spike in attention paid to to Sam Gilliam since Rashid Johnson staged an exhibition of his work at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles in 2013. “Rashid’s generation of artists, who have enjoyed greater success than the earlier generation, are using their flex,” says the gallerist Alexander Gray.

Installation view of a work by Sam Gilliam at “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” at the Brooklyn Museum. Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum.

Many are wielding the influence afforded them by their relationships with blue-chip galleries to broaden the field and expand curators’ and collectors’ knowledge. Artists who were never considered by some of the most powerful institutions are “now in major museums, primarily because of who is handling them,” says the New York-based dealer Peg Alston—who opened her doors in 1972 when the market for work by African American artists “was zero.” It is “unprecedented that the work of so many African American artists is so internationally known,” she says, adding, “the art hasn’t changed—it’s always been of the same quality.”

Marc Payot, a partner and vice president of Hauser & Wirth, credits Bradford, who joined the roster in 2015, for spurring the gallery to sign the artists Amy Sherald and the late Jack Whitten. And Mnuchin Gallery’s Sukanya Rajaratnam says she first began thinking of organizing a show of work by the 92-year-old abstract painter Ed Clark after speaking about him with David Hammons, who happens to own one of the largest collections of Clark’s work. Last week, the gallery opened the first major Clark exhibition in New York since 1980.

“The collateral effect is very powerful,” says Nicola Vassell, the curator of the collection assembled by the music producer Kasseem Dean (aka Swizz Beatz). “What I call the artist ‘industrial-complex’ begins to take on a different kind of purpose.” Furthermore, she notes, there is a growing class of wealthy black patrons, including Dean, who “look like the artists and are operating in the sphere of power on the buying side.”

In addition to recent converts, a number of dedicated African American collectors have sought to support artists from their own communities for decades—and now, their children are continuing the tradition. “My three girls went to basically an all-white school and I was concerned about the images they were seeing,” says Stella Jones, who closed her OB/GYN practice to open a gallery of her own in New Orleans in 1996. “I wanted them to see themselves on our walls.”

Installation view “Ed Clark: A Survey” at Mnuchin Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel, courtesy of Mnuchin Gallery.

The correction is only just beginning, experts say. A recent study by City University of New York noted that more than 88 percent of American artists represented by top New York galleries are white. The dynamics have not changed significantly since the artist Howardena Pindell took it upon herself to document the woefully homogenous demographics of galleries and museums in the 1980s and ’90s. “The museums often let the galleries do the primary sifting of artists,” she wrote. “If you are locked out at this level you are locked out at all other levels because each feeds the other.”

The historic lack of mainstream attention creates real potential for market growth. “From a dealer’s point of view, there is a huge opportunity—and not because they are African American, but because they are great artists,” Payot says. Despite the triumphant headlines touting new auction records, a full re-appraisal has only just begun. He adds: “Yes, we are moving in the right direction but, take out the top segment, and progress is much less than people think.”

Additional research by Chelsea Perkins and Dylan Sherman.

This story is part of a research project on the presence of work by African American artists in museums and the market over the past decade. For more, see our examination of museums; three case studies on artists from three different generations; visualizations of our findings; and our methodology.