Art History

Here Are 3 Facts About Richard Serra’s ‘Tilted Arc’—A Sculpture So Controversial It Was Put on Trial

The monumental sculpture, which was installed in Federal Plaza in Lower Manhattan from 1981 to 1989, posited free speech considerations against the role of public opinion.

In 1981, American artist Richard Serra unveiled Tilted Arc—a monumental sculpture made of Cor-ten steel measuring 12 feet high and 120 feet long—installed in Federal Plaza in Lower Manhattan. The 15-ton work had been commissioned by the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) as part of a government program devoting one-half of one percent of federal building budgets to permanent public art installations.

Tilted Arc, which as the name suggests was slightly tilted, was made site-specifically for the outdoor plaza in front of the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building, and divided the space like a steel wave. Serra had spent two years conceptualizing the work and studying the patterns of pedestrians, including the workers hurriedly crossing the space to and from their offices. The brutally graceful curvilinear sculpture bisected the plaza. Serra intended to elicit a connection between those walking through the space and their surroundings. Tilted Arc did just that, and perhaps too well. The installation unleashed a torrent of reactions from praise to consternation to outright outrage.

Unfortunately, the public had not been adequately informed of the work’s parameters, and many local office and construction workers were upset by the sculpture. They said the sculpture obstructed the plaza’s use as both a thoroughfare and a recreational space. A petition of 1,300 signatures from government employees working in Federal Plaza was quickly garnered, calling for Tilted Arc’s removal. Others, however, celebrated the sculpture as a powerful, lyrical form that countered the functional and drab office building, a provocative gesture set in a lifeless corporate plaza. The GSA originally stood by the sculpture, but pressure mounted in 1984 when William Diamond, a Reagan appointee, was named the GSA administrator. In 1985, Diamond would orchestrate a controversial public forum over the future of Tilted Arc, in which federal workers, art critics, artists, and Serra himself would defend their positions on the sculpture (read on for more details). Though 122 people had given testimony in favor of the sculpture, and 58 against it, led by Diamond, the GSA voted 4–1 to remove it. In 1989 Tilted Arc was dismantled and removed from Federal Plaza. In remembrance of Serra, who recently passed away at the age of 85, we took a closer look at Tilted Arc, his more infamous sculpture, and found three facts that might offer insights.

Serra Wanted Tilted Arc to Be Experienced Physically, Rather Than Visually

Richard Serra, Tilted Arc (1981). Courtesy Frank Martin/BIPs/Getty Images.

Tilted Arc celebrated Serra’s deepest artistic ideals and harkened to his earliest inspiration. The artist was born in 1938, the second of three boys to a working-class family in San Francisco. His Spanish-born father was employed, for a time as a pipefitter, in a Bay Area shipyard. Memories of visiting the yard made an indelible impression on the young Serra, who was mesmerized, on one occasion, by witnessing a hulking ship launched into the ocean and suddenly floating. “All the raw material that I needed is contained in the reserve of this memory,” he later recalled.

For Serra, the monumental could become lyrical through its physicality. When it came to the commission at Federal Plaza, rather than aiming to create a public sculpture that could be registered passively from a distance, Serra aimed for haptic engagement. Countering what he perceived as the ugliness and oppressive banality of the plaza, Serra sought for the public to find dialogue within the context of the sculpture itself. Tilted Arc, Serra said, was intended to “cross the entire space, blocking the view from the street to the courthouse and vice versa…It will be a very slow arc that will encompass the people who walk on the plaza in its volume…. After the piece is created, the space will be understood primarily as a function of the sculpture.” The obstruction of sight lines and walkways, intentional on Serra’s part, would become two major points of contention for those who used the plaza daily. These objections made no impression on Serra, who said “I don’t think it is the function of art to be pleasing…Art is not democratic. It is not for the people.”

It Faced the Court of Public Opinion—But Changed Laws, Too

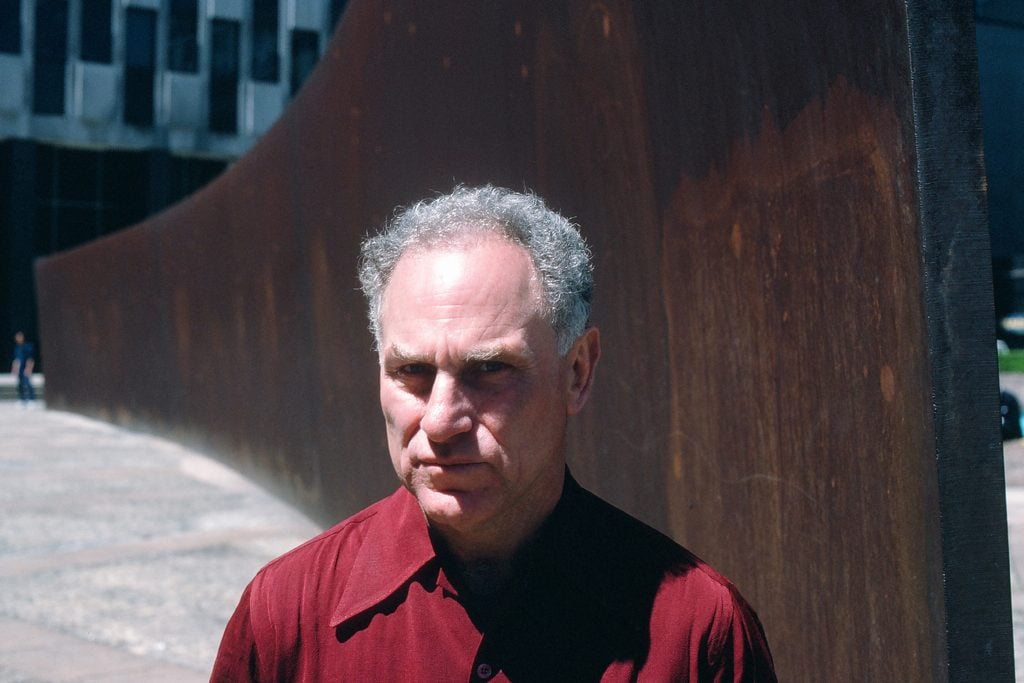

Portrait of American artist and sculptor Richard Serra as he poses with his massive steel sculpture Tilted Arc (1981) in Federal Plaza, New York, New York, mid-1980s. The sculpture was the subject of much public debate and controversy and was eventually dismantled and scrapped in 1989. Photo: Oliver Morris/Getty Images.

Long before William Diamond called a public hearing on Tilted Arc, critics had voiced full-throated opinions. In 1981, Grace Glueck of the New York Times, wrote, “Tilted Arc is an awkward, bullying piece that may conceivably be the ugliest outdoor work of art in the city.” Another critic described the work as “attacking the awful by increasing the awfulness.” Critic Michael Brenson, took the opposing view, describing Tilted Arc as “silent and private.” By the mid-1980s, the sculpture was at the center of a culture wars. Among the accusations lobbed were that it attracted graffiti and rats and even that terrorists could potentially employ it.

In April 1985, the GSA called upon the public to weigh-in. “[F]or the three-and-one-half years since the sculpture’s installation, we have received ongoing complaints from individuals and community organizations, who feel the plaza’s use as a recreational and performance facility has been destroyed,” Diamond explained. The testimonies at the March 1985 hearings were passionate, outrageous, and, at times, comical. Art professionals, including artists, curators, gallerists, and others, rallied in support of the work—among them were Philip Glass, Rosalind Krauss, Keith Haring, Claes Oldenburg, Abigail Solomon Godeau, and Douglas Crimp. “The kind of vector Tilted Arc explores is that of vision,” stated Krauss in the forum, “More specifically, what it means for vision to be invested with a purpose, so that if we look out into space it is not just a vacant stare that we cast in front of us, but an act of looking that expects to find an object, a direction, a goal.” Joan Mondale, wife of former Vice-President Walter Mondale, who had worked with GSA, defended the piece, saying “Sculpture which may be provocative to our eyes can be seen more clearly by those who come after us.” Serra testified forcefully, too, remarking “It is bogus and false to say that the social function plaza is destroyed. Also, the experience of art itself is a social function.”

Opponents of the sculpture were perhaps more colorful in their remarks. One worker wondered why the Federal government had paid $175,000 for “a rusted metal wall.” Another remarked that, “Transients have actually been seen urinating upon it, and in short the plaza has become a place to avoid, indeed an embarrassment.” Many openly wondered about the role of public opinion when it came to federally funded public art. Others saw the removal of Tilted Arc as a violation of free speech or, at least, a violation of Serra’s agreement with the GSA, which had been made for a permanent sculpture. The GSA ultimately ruled to remove the sculpture, and while Serra would sue GSA in response, he would lose his court battle. In 1989, under the cover of darkness, the sculpture would be removed.

The controversies that surrounded Tilted Arc would bring about legal changes, too. In 1988, the GSA amended its policies so that the public would be granted more awareness of future artistic projects. Meanwhile, the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA) was passed in 1990, adding an amendment to the Copyright Act of 1976, allowing artists the right to decide the attribution or integrity of a work.

“To Move Tilted Arc Is to Destroy Tilted Arc”

Tilted Arc prior to its removal at Federal Plaza, New York, May 10, 1985. Photo by Robert R. McElroy/Getty Images.

Amid these controversies, Serra had passionately declared, “To move Tilted Arc is to destroy Tilted Arc.”The sculpture, he argued, would cease to be his vision if removed from the plaza, given the site-specific considerations he had made in conceiving the work. Despite his best efforts, just this occurred. The sculpture was cut into three pieces and hauled out of Federal Square on trucks. These steel remnants were put in storage in a warehouse in Brooklyn and were moved again to Maryland in 1999. ‘The main thing is that we are taking good care of it; it is being treated with respect,” said Diamond, following its removal of the sculpture, adding that “open space” would be the new art on view in the plaza. Though the GSA had claimed it was relocating the work, Tilted Arc was never reassembled. Serra considered the work destroyed, rather than removed. He claimed that the GSA had turned the sculpture into a “mobile, marketable product” and that the ruling had set “a precedent for the priority of property rights over free expression and moral rights of artists.” Today, Federal Plaza is home—not to monumental sculpture—but to benches and a smattering of landscaping.