The writhing carcasses of alien creatures hover above a post-apocalyptic landscape in Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya’s solo show at Murmurs L.A. Made from trash, slimy silicone, and taxidermied animal parts, these monstrous works ooze and dribble from their protuberances, alluding to decay, death, and the carnal while encoding a mythological metaphor about dystopic survival. Like many of his Latinx peers, Montoya is concerned with ambiguous subjects who live in the shadows: night shift workers, the invisible labor force, immigrants, queer and othered communities. Yet he’s one of few challenging dominant tastes in Latinx art that favor representational, pop aesthetics, or explicit cultural motifs. Instead, Montoya’s work uses the abject and the fantastic to make critical work building on familiar narratives of trauma and resilience. His show “Ex Situ Canis Latrans” investigates the unsightly, challenges notions of taste, and uses the imaginative as material, making Montoya one of the most experimental and daring artists of our moment.

Two massive sculptures form the protagonists in “Ex Situ Canis Latrans.” One is suspended in parts like wriggling tentacles, and is named Tlahuelpuchi (2021); the other is a more fully formed conglomerate mass named A Being Mistakenly Called ‘La Nave de Kylo Ren’ (2021).

The latter hovers above a platform loaded with dark black rocks, formed from a fusion of discarded motor oil and desert sand. Styrofoam from Chinese take-out and packing materials—some stained with terracotta dirt—are assembled as cityscapes or small-scale renderings of past civilizations on the floor throughout the gallery. A small back room with walls painted black and an eerie soundtrack hold smaller avian sculptures ensconced on the wall.

Installation view of Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya, A Being Mistakenly Called ‘La Nave de Kylo Ren’ (2021) at Murmurs L.A. Image courtesy Murmurs L.A.

Like the gory aftermath of a car crash, animal appendages are rearranged into a mash of gooey flesh, horns, and auto parts in A Being Mistakenly Called ‘La Nave de Kylo Ren’ (2021). Yet the object-being seems to have survived by absorbing the remnants of human waste, transforming blind spot mirrors into extra eyes and boom box parts into protective shields.

Most materials embedded in the silicone structure—including goat legs and disposable razors—are refuse Montoya gathered from the desert around Juarez, the highways in L.A., and on other metropolitan adventures. Like someone cataloguing pieces of treasure, Montoya documents each discovery with glee in the material listed in the description for each of the works. One reads “motorcycle part of a man with an inflated ego driving too fast on a sharp turn on Mcnutt Rd.”

Detail of Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya, A Being Mistakenly Called ‘La Nave de Kylo Ren’ (2021) at Murmurs L.A. Image courtesy Murmurs L.A.

As the objects are woven or fashioned into the sculpture-beings that dangle from the warehouse ceiling, the implied usage and characteristics of the materials transform. Car fenders, normally heavy and onerous, fly through the air like bat wings. T-shirts that once cloaked the torso have been dipped in tan-colored silicone and now look like the membrane of entrails.

After you realize the inversion of purpose in Montoya’s use of these objects, the sculpture begins to reveal its story and uncanny animism. From precarious, valueless trash, it enters a process of “always becoming,” a characteristic of queer assemblage described by the late scholar of queer, Latinx, and performance studies Jose Esteban Muñoz. In an essay titled “Performing the Bestiary,” Muñoz wrote, “Becoming is simply a constant process of flight, change, movement within the assemblage… Becoming is a kind of deterritorialization of the body itself.”

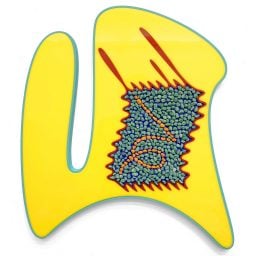

Detail of Rodriguez Montoya, Tlahuelpuchi (2021) in “Ex Situ Canis Latrans” at Murmurs L.A. Image courtesy Murmurs L.A.

Like a vision of squirming snakes suspended midair, Tlahuelpuchi (2021) also conveys a state of becoming. Brown horns jut from the multi-part creature’s greenish-blue skin—the color of iridescent jade—while crumpled car parts protect her vulnerable exterior like turtle shells. The tentacles hold golf balls resembling lusty turtle eggs at the brink of bulging from their nests, of the kind found at the meeting of three tributaries in a canyon in Juarez. Adapting the Tlaxcallan myth of a female vampire named Tlalepuelchi in a text he wrote to accompany the Murmurs show, Montoya writes that “Tlahuelpuchi is a vampire born before linear time… born to the people who sweep quetzal feathers with makeshift brooms.”

Construction workers and those who work the night shift—like Montoya’s own father—influence the cunning, dexterous nature embodied by these extraordinary creatures or imagined characters. “I saw this woman picking up trash with a beautiful stick she made specifically to pick up trash,” Montoya told me, explaining the inspiration for his found object assemblage. “It was such a beautiful stick. She led me to think about a creature going through detritus to feed itself.” For Montoya, “creating mythology allows for the small gestures to become hyper. I can allow the seemingly mundane things in my day-to-day to become these gorgeous gestures.”

Detail of Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya, A Being Mistakenly Called ‘La Nave de Kylo Ren’ (2021) at Murmurs L.A. Image courtesy Murmurs L.A.

Montoya’s work reminds me that mythologies are constantly being socially constructed, and they’re not all positive, such as conspiracies surrounding the vaccine. Ancient rulers also spread certain folklore to sustain their power. Devising mythologies is a method societies use to fill in the gaps about what they don’t understand or what they fear. For a young Montoya, the stories of ghosts, vampires, and witches helped him comprehend ambiguous characters outside the heteronormative realm. For him, mythmaking has been a form of psychological survival.

The mythology of shapeshifting employed by Montoya’s organisms is described by the godmother of Chicana queer feminist theory Gloria Anzaldúa as “nahualismo.” She believed la naguala to be “a concept borrowed from indigenous thought, serv[ing] as a vehicle for deconstructing and decolonizing embodiment and being.” Anzaldúa describes shapeshifters as outsiders who cannot reconcile their multiple identities and are forced to inhabit life on the edges of society. Of course, shapeshifting is also an obvious metaphor for a practice that many othered communities rely on to move through the world. The first half of the show’s title “Ex Situ” is Latin, meaning to remove in order that an endangered species survives.

Installation view of work in Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya at Murmurs L.A. Image courtesy Murmurs L.A.

Montoya is known for his love of the unpalatable, the decaying, and the putrid. Details like the milky liquid made from silicone that oozes a single drop from the tip of one sculpture’s horse hoof provide evidence. “If you can get past the filthiness of a thing, you can experience something rare and beautiful,” he tells me, describing unexpectedly majestic encounters he’s had with roadkill.

Montoya’s imaginative world is an illustration of an abysmal reality. “For me, the work is a visual metaphor that allows for one to reckon with trauma but also to go past it. How do you move forward? How do you contain a body that is no longer whole?,” he asks. Though themes of adaptation, resiliency, and trauma dominate discussions around artists of color, it’s rare to see the vehicles of fantasy, narrative, and the abject used to interrogate them. Montoya’s body of work is experimental in the sense that it pushes against the representational aesthetics and cultural performativity that dominate what is considered ‘Latinx’ art.

Installation view of work in Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya’s “Ex Situ Canis Latrans” at Murmurs L.A. Image courtesy Murmurs L.A.

The work is confrontational and immersive in its ability to push its viewer to question their aesthetics and unpack their repulsion. A lot of artwork fixates on the raw wound. I argue Montoya’s work goes a step further in pushing the viewer to meditate on the unpleasant wound in order to witness it’s crystallization into scab and then scar. “It’s almost like you know you’re fucked, but you’re still going through it,” the artist explained. “We’re in this otherness, looking at the shadows, and we’re able to see the fucked up America. But It feels like a collective experience that we’re all living through and edging ourselves not out but through it.”

“Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya: Ex Situ Canis Latrans” is on view at Murmurs L.A., 1411 Newton St., Los Angeles, through September 26, 2021.