Art Criticism

‘Spirit Keepers’ Showcases Three Black Artists’ Vivid Invocations to Other Realms

The uplifting and complex "Spirit Keepers" is now on view at New York's Eric Firestone Gallery. The trio of artists use color and form to reach for a higher power.

Cosmic and phantasmagorical sculptures by octogenarian artist Walter C. Jackson anchor the group exhibition “Spirit Keepers.” A pair of six-foot-tall totemic forms made of aluminum, wood, plastic, and sisal command the center of the room, an example of Jackson’s practice since the 1970s, creating sculptures that function as passageways, connecting ritual and technology, past and future.

“Spirit Keepers” runs until December 21 at New York’s Eric Firestone Gallery and puts Jackson’s work in conversation with two other Black artists also born in the U.S. prior to the civil rights movement: Marie Johnson-Calloway, who passed away in 2018 at the age of 97, best-known for mixed-media collages incorporating fabric, and David MacDonald, born in 1945, a ceramic artist interested in the spiritual qualities of the vessel. Collective memory and African traditions play a role in all three artists’ work.

Walter C Jackson, S5-G9-H1 (1983). Courtesy of Eric Gladstone Gallery.

The works represented in the show range from the 1970s to the 1990s. In the 1970s, many Black American artists were incorporating ancestral African spirituality and craft into their work, and the artists in “Spirit Keepers” were no exception. During this period, MacDonald, for example, started taking inspiration from different African cultures’ traditions of adornment—from ritual tattooing and body modification to the decoration of pottery, architecture, and textiles.

David MacDonald, Beaded Nyama Form (1979). Courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery.

MacDonald’s Beaded Nyama Form (1979), for example, is a beaded and flocked fertility vessel about three-and-half-feet tall, with a curvaceous, undulating silhouette, the sinuous grooves of its richly patterned clay taking on the quality of skin raised by ritual scarification. After growing up in New Jersey, MacDonald attended the historically-Black Hampton University on an athletics scholarship in the 1960s before completing an MFA at Syracuse University. He went on to become a professor in the School of Art at Syracuse for four decades, during which time he continued his own artistic practice making work, including the vessels featured in this show. His work is in the permanent collections of the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Montclair Art Museum, and the Everson Museum of Art.

Marie Johnson-Calloway, First Vote (1987). Courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery.

At Firestone, Johnson-Calloway’s mixed-media collages stand out for their narrative-driven compositions. These pictorial works, which the artist calls “sculpted paintings,” date back to the 1970s and 80s, when Johnson-Calloway was a professor at San Jose State University. At the time, the artist was also exhibiting widely, including at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1977 and the Oakland Museum of California in 1987, groundbreaking for a Black woman then. Johnson-Calloway references both trials of class mobility and racial equality specific to this era.

Senior CEO from 1984 translates the period’s glamorization of corporate culture combining an acrylic portrait of a sunglasses-wearing silver-haired man radiating a collage of neckties like a saint’s aureola while First Vote features figures in Batik-patterned dresses and the South African flag. This depiction, however, is from 1987 pre-dating, the first time Black women were able to vote in South Africa, three years before apartheid ended and seven years before the first general elections open to all races.

Marie Johnson-Calloway, Senior CEO (1987). Courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery.

In works like this one, Johnson-Calloway projects hope for the socioeconomic advancement of Black people, reflective of her own biography and activism. Moving west to escape Baltimore’s segregation, in 1954 Johnson-Calloway became San Jose’s first African-American public school teacher. Later she participated in the historic 1965 Selma, Alabama march with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., an event that redefined the content of her work, inspiring her to favor direct depictions of Black life and everyday heroes. Her practice also became more three-dimensional, this assemblage style she developed on full display in “Spirit Keepers” with pieces incorporating cowrie shells, buttons, plastic flowers, and hair. Whether enshrining her own ancestors or community struggles, Johnson-Calloway created artworks that function as memory keepers, preserving and monumentalizing familial and communal legacies. Prior to her passing in 2018, her work was already represented in museum collections and the subject of institutional retrospectives as well as being included in the Hammer Museum exhibition “Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980” in 2011.

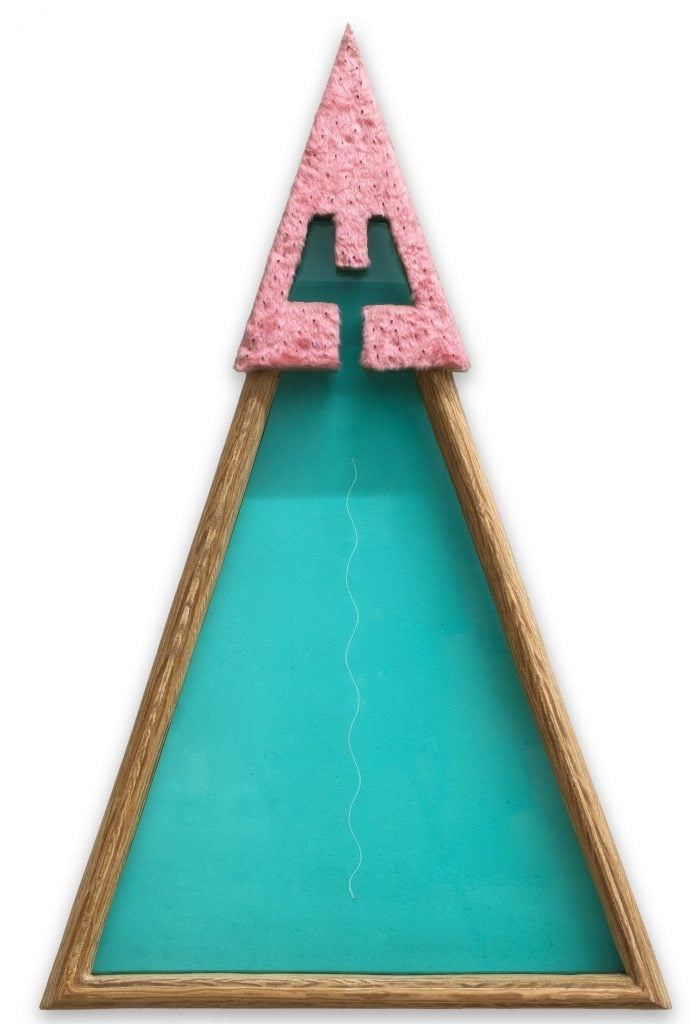

Walter C Jackson, SPIRIT KEEPER NO.4 (1976). Courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery.

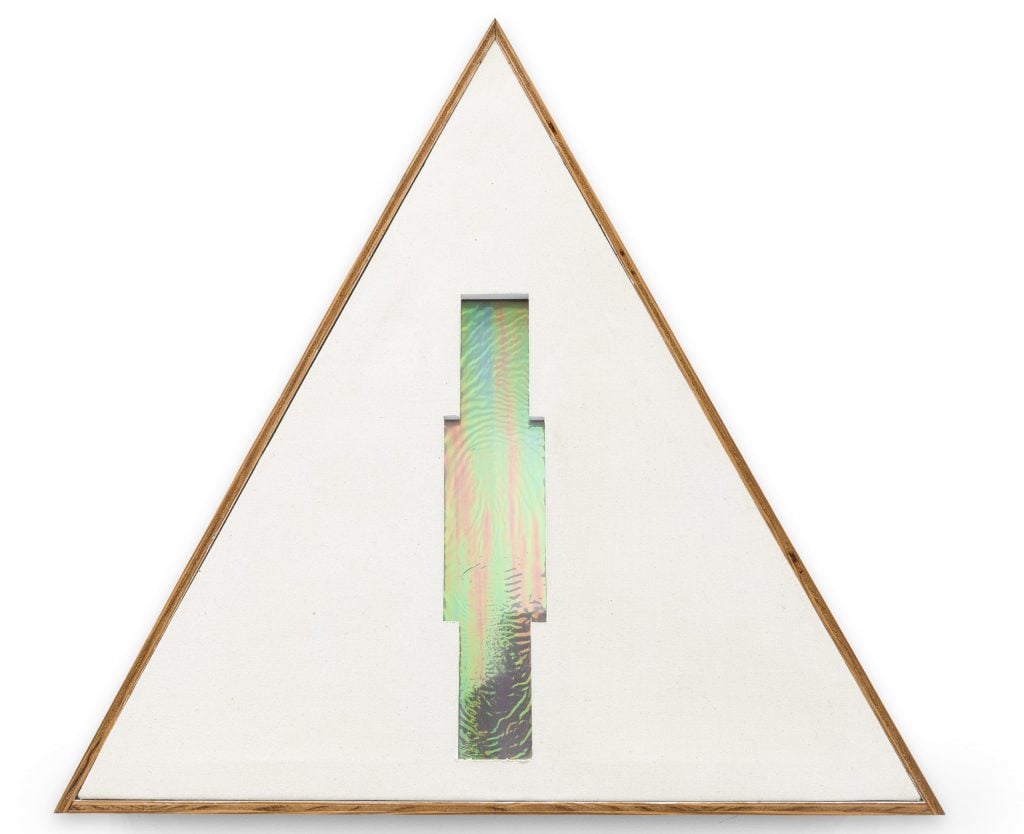

While also from the 1970s and 80s, Jackson’s sculptures feel the most contemporary of the three artists. His geometric forms mix natural and synthetic materials as they draw from West African cosmology and architectural references including Egyptian pyramids, Moorish doorways, and American Southern churches. The resulting structures evoke organicism and divinity but also new-age futurity. Triangular forms feature prominently in several of the pieces. Jackson’s pink triangle Portal NO. 4 from 1985 feels analogous to the pink triangle that the pioneering AIDS activism group ACT UP adopted not long before their 1987 Silence=Death campaign. When I asked Jackson about it at the opening, he explained I wasn’t the first person to note the correlation. “I made them at the same time as the crisis,” he said. “No, they are actually not referencing that. They are meant to be portals to a different time and place, evoking Egypt and the significance of the shape in that and other African cultures.”

Walter C Jackson, Thoughts on Posterity #1 (1990). Courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery.

Like MacDonald and Johnson-Calloway, Jackson was able to support his sculpture practice with a longtime career as an arts educator. Hailing from Jackson, Mississippi, he went on to complete graduate studies and then teach in Memphis at the University of Tennessee before transitioning to New York in the 1980s, teaching at City University of New York. He then worked at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, and as the executive director of the Bronx River Arts Center in the 1990s. Today the 84-year-old lives and works in rural New York, continuing his explorations into what he calls “communal iconography,” melding traditional symbols with more modern information systems, including cybernetics. His work is held in several public collections, among them The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and The Studio Museum in Harlem, while Firestone Gallery also featured two of his pieces in their recent presentation at the Armory in September.

Functioning as a mini-retrospective of sorts, Firestone’s exhibition spotlights three Black American artists who, while not household names, are all important figures, their individual narratives and diverse approaches to engaging spiritualism through sculpture capturing inflection points in broader society and art near the end of the 20th century. Honoring ancestry and an interconnectivity that transcends place and time, Jackson, MacDonald, and Johnson-Calloway, each through their own formal strategies, model the artist’s role as a guardian and channel.