Crime

U.S. Returns Millions in Antique Books Stolen by Suicidal Librarian to Sweden

Authorities hope that more books will be recovered.

Authorities hope that more books will be recovered.

Sarah Cascone

Rare 17th-century books were returned today to the National Library of Sweden by the U.S. Attorney’s Office, artnet News learned during a repatriation ceremony that took place today in downtown Manhattan.

The antiques had been stolen in the 1990s by Anders Burius, a senior librarian who pilfered at least 56 books from the library, according to court documents.

During the ceremony, which was attended by Sweden’s national librarian, Gunilla Herdenberg, deputy U.S. attorney Richard Zabel expressed his pride in assisting in the return of the books, noting that “in many ways, the library contains the cultural memory of Sweden. The theft of a piece of a nation’s memory and heritage creates holes in its intellectual soul.”

Burius’s crime captivated the Swedish imagination, especially after he killed himself following his confession and arrest in 2004. While free on bail, he slit his wrists and cut his apartment’s gas line, causing a explosion that injured a dozen people. His exploits have since been the subject of a Swedish radio documentary and television mini-series.

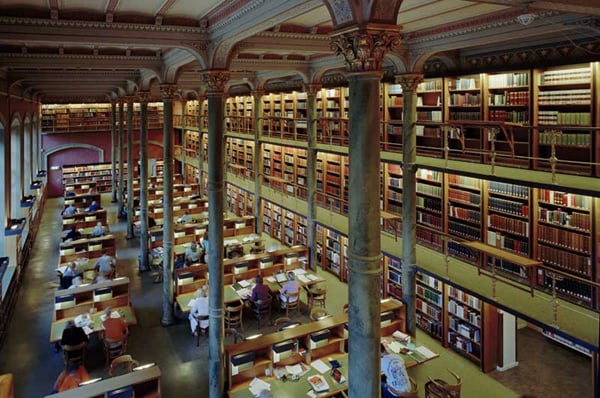

The National Library of Sweden.

Photo: courtesy European Library.

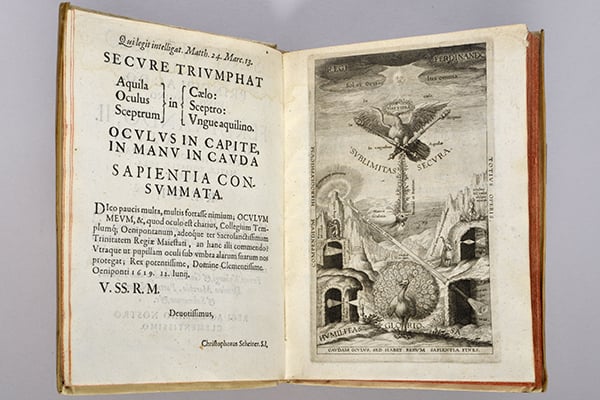

The books returned today both have significant historical importance. For example, Nicolo Sabbattini’s Practica di Fabricar Scene, e machine ne’teatri (1638) is considered the first book devoted to theatrical stage design, while Christopher Scheiner’s Oculus (1619) is a landmark work in the history of optics, and helped in the development of external lenses to improve eyesight.

After stealing the books, Burius sold them to the German auction house Ketterer Kunst. Swedish authorities now believe that 13 of those books eventually made their way to the U.S., including those by Sabbattini and Scheiner.

In 1999, New York bookseller Jonathan A. Hill purchased Oculus, unaware of its illicit origins. He later sold the volume to Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Richard Lan, who co-runs Martayan Lan rare books in New York, purchased the Sabbattini book in 2001, also without knowledge of its theft.

Christopher Scheiner’s Oculus (1619).

Photo: courtesy US Attorney’s Office.

When the FBI began investigating the case, they contacted the university and Lan, who both voluntarily agreed to return the antique books to Sweden. So far, five volumes stolen by Burius have been recovered.

A full list of the missing works is available on the library website. “We welcome any information concerning the whereabouts of these stolen books so that they can be promptly returned to the library,” Howard N. Spiegler, co-chair of Herrick’s Art Law Group, which represents the library and assisted the U.S. government in the investigation, said in a statement.

Following the ceremony, Hill demanded to know how such a large-scale theft could have gone undetected for so long by the library’s security, and asked Herdenberg to apologize for the “considerable financial loss” suffered by those who had fallen victim to the theft.

“The security wasn’t that bad,” Herdenberg insisted. “It was an an inside [job] and it’s hard.” She did not address Hill’s request for an apology, but stressed that increased security measures had since been implemented at the library.