Art History

Why Walter De Maria’s ‘The Lightning Field’ Remains a Striking Work of Land Art

Here are three things you may not know about the iconic and remote installation.

Here are three things you may not know about the iconic and remote installation.

Katie White

In the high desert of Northwestern New Mexico, 400 stainless steel poles jut out of the desolate landscape. The poles, each measuring two inches in diameter, are spaced evenly, at intervals of 220 feet, forming an illusory grid running one mile by one kilometer.

This striking installation forms The Lightning Field—Walter De Maria’s iconic land artwork from 1977—and a masterpiece of Minimalist art. A remote destination visited by only the most devoted art lovers, The Lightning Field has become mythic in its allure—an American temple on a hill set amid the natural world.

The Dia Art Foundation commissioned the work from De Maria at the height of his fame. The artist was a leading proponent of Minimalism, an artistic movement focused on material exaction that sprung up in the 1960s and ‘70s. “What you see is what you see,” Frank Stella famously quipped of the movement. During these years, land art concurrently emerged as a compelling language for artists aiming to work outside the commodified gallery system and traditional mediums. A number of Minimalist artists engaged these large-scale interventions in their environments. Upon its creation, The Lightning Field joined the ranks of Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (1969), Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970), and Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1976). Ambitious in scale and intent, these creations emphasized the role of time and space.

Nancy Holt, Sun Tunnels (1973-76) Great Basin Desert, Utah. Photograph: Nancy Holt. Collection Dia Art Foundation with support from Holt/Smithson Foundation © Holt/Smithson Foundation and Dia Art Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

The Lightning Field is a work we know almost everything about. De Maria, along with a team from Dia, scoured California and much of Southwest for the ideal venue for the installation, ultimately choosing a location in New Mexico some 11½ miles east of the Continental Divide and at an elevation of 7,200 feet.

De Maria conceived the work in excruciatingly and intentionally precise detail, and its genesis and life have been assiduously detailed by the Dia Art Foundation since. In fact, it is that very exacting precision that imbues the work with its transcendent spirit.

For instance, the poles, which are aligned in rows of 25, are so carefully installed that only a single pole is visible when viewed from straight on. The pointed tips of the poles, similarly, each reach the same height. De Maria imagined the work as a plane that could “support an imaginary sheet of glass.” But the poles themselves vary in height, averaging 20 feet, 7 and a half inches in height, but ranging from 15 feet to 26 feet 9 inches. The terrain underfoot, which appears flat from a distance, is in truth quite craggy and uneven. Together, the work consists of almost 38,000 pounds of stainless steel.

Despite the glut of minute details known about the work and its cult-like fame, an air of mystery still shrouds The Lightning Field. As summer winds its way around the corner, and brings with it peak electrical storm season, we took a closer look at this icon of American art. Here are three facts that may help you see The Lightning Field in a new way.

1. The Earth Is Part of the Work

Walter De Maria, The Lightning Field (1977). Long-term installation, western New Mexico. © Estate of Walter De Maria. Photo: John Cliett, Image courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

Treks to The Lightning Field are often described as pilgrimages—and for good reason. The installation is, according to De Maria’s wishes, meant to be experienced in isolation. Only six people are allowed to visit the work at a time and reservations are extremely limited.

In his lifetime De Maria kept the work’s precise location secret. Even now, the location remains obtuse. Visitors arrive at the Dia Foundation building in the small 4-block town of Quemado in the early afternoon, pile into an SUV, and are driven 45 minutes to a cabin, where they will spend the night. The cabin predates The Lightning Field, which it stands adjacent to. The cabin is an assiduously restored homestead from the turn of the century, and a reminder of the people who toiled in unforgiving landscapes in exchange for a parcel of land.

“The land is not the setting for the work but a part of the work,” De Maria explained in his conception of The Lightning Field. The land develops the work in several ways—firstly, in its remoteness and its elevation, the work becomes akin to a pilgrimage site. In a two-part essay about The Lightning Field written for Gagosian Quarterly, art historian and curator John Elderfield draws a comparison to the nearby pilgrimage destination of San Estevan Del Rey Mission Church at Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, a National Historic Landmark. He writes, “Christianity in the late-antique world, has explained that the cult of the saints required that their remains be placed outside the walls of the city, a practice eventually leading to the creation of relic-rich shrines that became the object of pilgrimages, often to far-off places.” He notes how Peter Brown, a scholar of Christian antiquity, in this book the Cult of Saints, references “the ‘therapy of distance’ created by a long pilgrimage carefully maintained tension between distance and proximity. This, he said, “ensured praesentia, the physical presence of the holy.” But, rather than offering a place of respite at the end of the journey, De Maria plunges visitors into dialogue with elements. Walking the grounds, one realizes how uneven the land is, and how treacherously muddy it is to navigate if it has recently rained—that the elusive desire for lightning to strike is more often than not supplanted by the realities of the body engaging with an arduous landscape.

2. Light, and the Potential for Lightning, Engages the Romantic Sublime

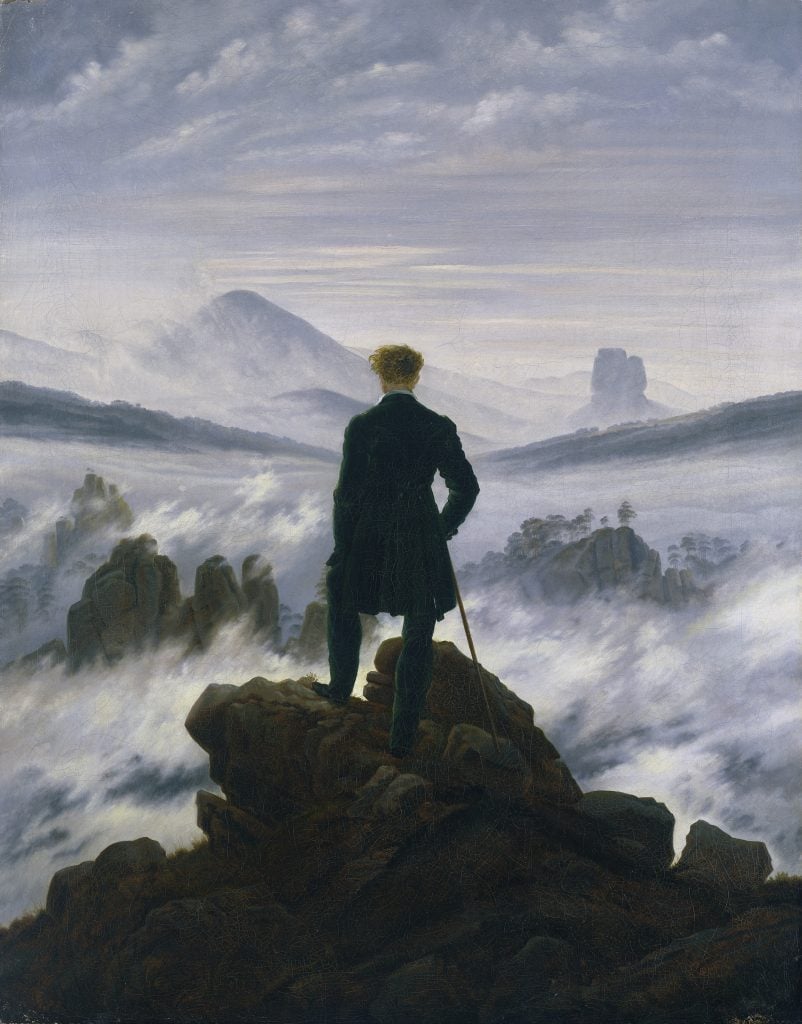

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, (c. 1817). Permanent loan from the Stiftung Hamburger Kunstsammlungen © SHK / Hamburger Kunsthalle / bpk. Photo: Elke Walford.

The Lightning Field is a work that keeps visitors in a state of suspended expectation and keen awareness of their environment. One way the work manages this is with the unpromised, but suggested, potential for lightning. It is known that De Maria chose this high desert location because of the frequency of lightning, which peaks in July and August. He also, of course, included “lightning” in the work’s name. Dia Art Foundation, however, emphasizes that the work can be experienced completely, and as De Maria intended, without seeing lightning (lightning remains a rare occurrence even at the height of summer).

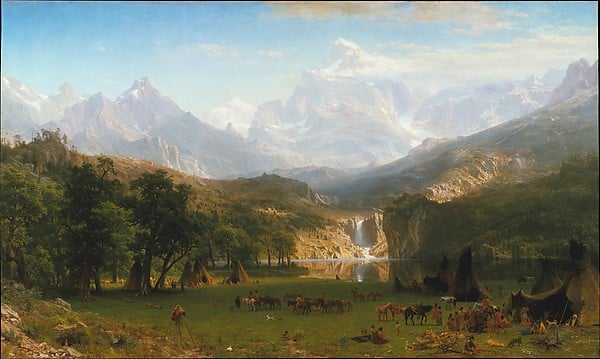

This tension, between the imagined possibility and experienced and perceived reality, draws viewers into a sustained and heightened sensitivity. In many ways, the work draws parallels to the experiences of the sublime, as described in the 18th and 19th centuries by Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant. The sublime, in these instances, described the powerful emotional experience of comprehending—even fleetingly—the vastness and magnitude of nature. The sublime is to be awe-struck, rather than overwhelmed. In the 19th century, artists of the Romantic movement tried to capture and evoke the sublimity of the natural world. Caspar David Friedrich, William Blake, Frederic Edwin Church, and Albert Bierstadt were among these artists; often their works feature lone figures, paused in moments of contemplation, while ensconced in massive landscapes.

Albert Bierstadt, The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak (1863).

Photo: courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Lightning Field works in much the same way. The six daily visitors can quite quickly lose sight of one another, leading to the effect of a solitary experience and a heightened state of contemplation. Photography is also prohibited, encouraging visitors to look at the work itself.

For artists of the Romantic era, light was a visual device to indicate an individual’s perceptual awakening. De Maria uses light—real light—similarly. In the height of summer, this stretch of New Mexico sees 14 and a half hours of daylight. “During the mid-portion of the day, seventy to ninety percent of the poles become virtually invisible due to the high angle of the sun.” De Maria wrote. As the sun charts its journey through the sky, one begins to perceive the vastness of The Lightning Field, and with it, the power of the sun more sublimely and completely.

“The Lightning Field is obscure, both in the sense of being difficult to perceive at once-especially at midday-and in being remote and troublesome to reach. Its central image is power—the sometimes lethal power of lightning,” wrote art historian John Beardsley in an essay on Land Art, “The privations of solitude and silence are integral to the experience of the work; it is vast, both in its own dimensions and in the setting it employs. And everywhere is the implication of infinity.” The sense of infinity is born of the work’s format—a potentially limitless expandable field—and, “ if not in the horizontal spread of the earth, then in the extraterrestrial dominions to which the work emphatically points.”

3. It Has Ancient Allegories

The Parthenon in the Acropolis of Athens. Photo by Nicolas Economou/NurPhoto via Getty Images.

With its columnar vertical rods, The Lightning Field has been likened by historians and writers to an ancient colonnaded temple, a contemporary Acropolis on a hill. In his essays, Elderfield draws a comparison to the Ionic Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, the largest known of these ancient temples, “longer than a football field and in one reconstructive plan comprising one hundred columns, of which only a portion of a single column remains.” The classical scholar Faya Causey, Elderfield notes, draws the prototype for The Lightning Field even further into history, to the “templum” of ancient Etruscan culture—open rectangular spaces without roofs that were “cut out”—as the name signifies—from the environment, and “oriented to the points of the compass, as is The Lightning Field”. In these spaces, priests would have awaited signs from the celestial realms, “notably lightning” Elderfield adds, “for the bolts were understood as communications from the gods.”