A Thomas Hart Benton painting is at the heart of a controversy at Indiana University, where a student petition is calling for a mural depicting hooded members of the Ku Klux Klan to be removed from a classroom. In response, the school has stopped holding classes in the room, the largest lecture hall on campus.

Nearly 1,600 signatories are asking the school to take down or cover the offending panel from A Social History of Indiana (1933), also known as the Indiana murals. But others are speaking up in support of the artwork, contending that Benton was looking to draw attention to the evils of the Klan.

“It is past time that Indiana University take a stand and denounce hate and intolerance in Indiana and on IU’s campus,” reads the petition, which argues that exposing students and faculty of color to the image of the KKK stands in violation of the school’s diversity policy and the student Right to Freedom From Discrimination.

In the mural, the Klansmen are seen alongside a reporter, photographer, and printer—a reference to the Pulitzer Prize-winning 1928 story that uncovered the KKK’s ties to the government and broke their political influence over the state. Similarly, Benton unapologetically depicted the ugly side of Missouri history, including lynchings and a slave auction, in his A Social History of Missouri murals for the state capitol building.

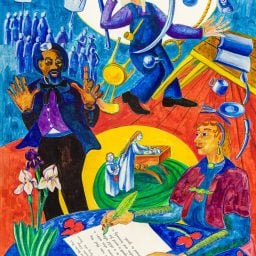

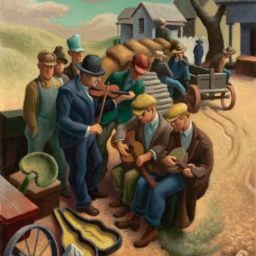

Thomas Hart Benton, A Social History of Indiana (1933), on view in the auditorium at the University of Indiana. Courtesy of University of Indiana.

“Like most great art, Benton’s murals require context and history,” said Lauren Robel, the school’s executive vice president and provost, in a statement, calling the works a national treasure. “Many well-meaning people, without having the opportunity to do that work, wrongly condemn the mural as racist simply because it depicts a racist organization and a hateful symbol.”

“It does not glorify or celebrate this particular dark episode of the KKK in Indiana, but instead shows that the state’s past has shameful moments the likes of which we do not want to see again, ever,” added James Wimbush, the university’s vice president for diversity, equity, and multicultural affairs, speaking to USA Today. “It’s important to understand the state’s history—the good and the bad.”

The petition acknowledges that Benton intended to denounce the Klan, but points out that the KKK is still active in the state today, claiming that “these are in fact modern depictions and not just depictions of a historical time in Indiana.” It calls the classroom housing the artwork “an environment that promotes a group known for discriminating against people of color, homosexuals, non Christians, and various other marginalized groups of people.”

Henry Adams, an art history professor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, has published an editorial in defense of Benton in the Conversation. He details the painter’s well-documented rejection of racism, from participating in the NAACP-organized 1935 exhibition, “An Art Commentary on Lynching,” at New York’s Arthur Newton Gallery to learning the African-American dialect Gullah.

Thomas Hart Benton, A Social History of Indiana (1933), on view in Woodburn Hall 100 at the University of Indiana. Courtesy of University of Indiana.

A Regionalist painter who painted scenes of everyday American life—think Grant Wood’s American Gothic—Benton was commissioned by the Indiana State Legislature to create the murals for the Indiana Hall at the “Century of Progress” exposition at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. Adams says the artist was likely chosen for the project “because of his progressive political views”—and because he could complete the massive project in time. (He used 10,000 eggs to create the 22-panel egg tempera work over the course of just six months.)

The murals were donated to Indiana University in 1940 and installed across three buildings on campus the following year. According to the school, the murals are quite delicate and cannot be removed without risk of damage. There was talk of having classes discuss the sensitive artworks, but some professors were uncomfortable moderating such potentially fraught conversations or did not want to devote class time to a subject unrelated to the course.

In hopes of ending the controversy without removing the mural, the school says it will now use the room containing the mural for activities other than classes.

“Covering the murals feels like censorship and runs counter to the expressed intent of the artist to make visible moments in history that some would rather forget,” said Robel. “Repurposing the room is the best accommodation of the multiple factors that the murals raise: our obligation to be a welcoming community to all of our students and facilitate their learning; our stewardship of this priceless art; and our obligation to stand firm in defense of artistic expression.”