Politics

With Monuments Falling All Over Europe, We Asked Historians and Artists to Weigh in on How They Should Be Replaced

Experts say there are no easy answers.

Experts say there are no easy answers.

Naomi Rea

Protesters in the English town of Bristol have reignited a fierce debate over the role of statuary in public spaces after they toppled a monument celebrating Edward Colston, a board member of the Royal African Company, the biggest slave-trading firm in British history, as one of the city’s “most virtuous and wisest sons.”

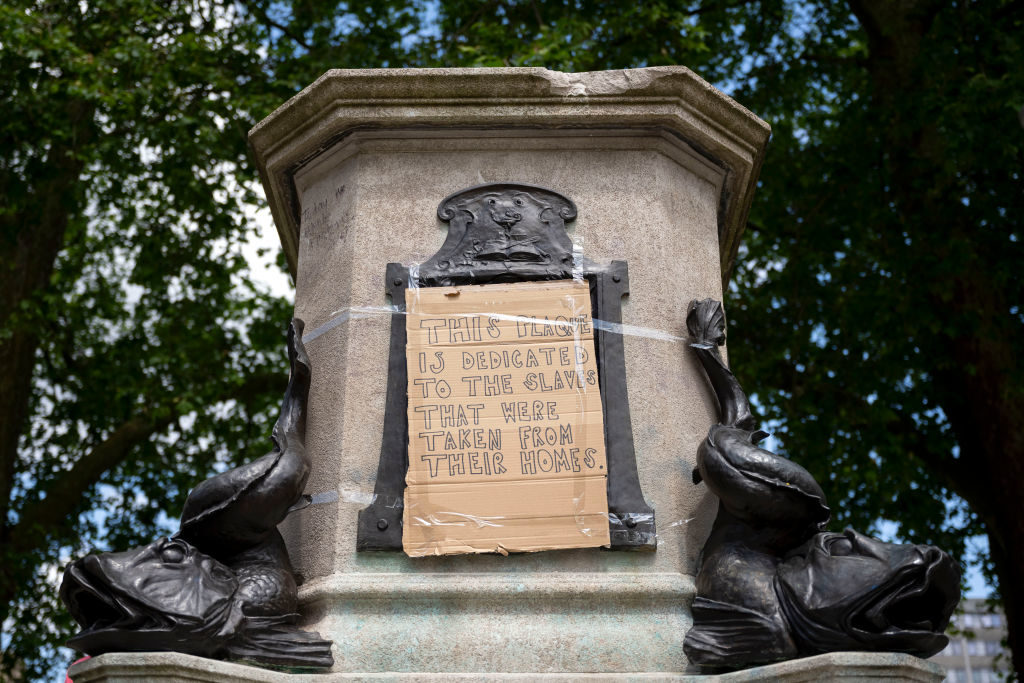

The statue was toppled and dumped into a harbor on June 7 after the Bristol City Council spent years equivocating over the wording of a plaque proposed in 2018 that would clarify Colston’s links to the slave trade. The statue was erected in 1895, more than 150 years after his death, and 88 years after Britain abolished the slave trade, to commemorate the gifting of his vast fortune to the city of Bristol.

Adding plaques and new wording to contextualize problematic statues has been a common method of dealing with Confederate monuments in the US, but in the UK, disputes over wording can drag on without closure. Oxford University has reviewed several such proposed plaques for its controversial statue of the Victorian Imperialist Cecil Rhodes, but none have yet been approved.

Moreover, some opponents of these measures are dissatisfied with the sanitizing language that is often used to contextualize monuments, which they say does not do enough to inspire people to think differently about historical legacies.

Protesters transporting the statue of Colston towards the river Avon. Photo by Giulia Spadafora/NurPhoto via Getty Images.

In Bristol, demonstrators took matters into their own hands, and activist groups around the UK are now organizing to topple more monuments, even as officials in some cities have begun to voluntarily remove them on their own.

Now the question is: what comes next?

Some have called for the Colston statue to remain in the harbor. (As the historian David Olusoga recently pointed out, the water burial is somewhat “poetic,” given that many of the victims of Colston’s enterprise drowned in the Middle Passage.) But the Bristol City Council has other plans, and has already fished the monument out of the water (but not before someone updated its location on Google Maps). The statue is now in secure storage and will be added to the city’s museums collection, although the council has given no indication of where or how it will be displayed.

“I don’t believe that you can erase history. It’s more dangerous to erase history,” the artist Yinka Shonibare tells Artnet News, adding that he feels the most appropriate setting for the felled monument is in a museum.

“If the community wants [monuments] to be removed, then they should be removed, but they should remain in public view, by creating museums for them, as a reminder so that we don’t make the same mistakes in the future,” Shonibare says.

Similarly, the director of the Victoria & Albert Museum’s V&A East Project, Gus Casely-Hayford, says the removal of the sculpture presents an opportunity for Bristol to confront the issue head on. “I could see the statue in its present state along with placards from the march as the culmination of a wider exploration of slavery and race at one of the city’s museums,” he says. (The artist Hew Locke suggests that the work could be installed in a museum “on its side, not resurrected up like an attractive statue.”)

But others say that statues like these cannot be properly contextualized in existing museum collections, which have their own already entrenched hierarchies of knowledge, and have called for these monuments to be displayed on their own.

“I think that there should be a real Museum of Colonization, like there is a museum of the Holocaust, so that people can reflect on that colonial fact,” says the Belgian historian Omar Ba.

The now-empty Edward Colston statue plinth. Photo by Matthew Horwood/Getty Images.

As for what to do with the empty plinth, nearly 45,000 people have signed a petition asking that it be used to memorialize a local civil-rights leader, Paul Stephenson, who led the 1963 Bristol Bus Boycott, which began after local transportation authorities refused to employ Black or Asian bus crews. His actions influenced the creation of the 1965 Race Relations Act, the first piece of legislation in the UK to outlaw racial discrimination.

Another suggestion, put forward by the London-based sculptor Sokari Douglas Camp, is to install in the space a permanent artwork commemorating the abolition of slavery. (Her work, All the world is now richer, which commemorates the end of slavery and salutes survivors of its legacy, was shown in Bristol Cathedral over the burial site of a number of slavers in 2013.)

“But there is a glass ceiling when proposals like this are brought forward,” Douglas Camp says. “This time of change is an opportunity to site the work on the Edward Colston site, if Bristolians are willing.”

But not everyone agrees that the statue of Colston should be permanently removed. Hew Locke, who has been reimagining public sculptures of problematic historic figures in his work since the 1980s, suggests that an artist be commissioned to make a permanent intervention on the statue itself.

“Insulting” the statue means that “you walk past it every day and you don’t ignore it anymore,” he says.

Hew Locke, Colston (RESTORATION series) (2006). Image courtesy the Artist, Hales Gallery and P·P·O·W. © Hew Locke. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2020.

An alternative solution would be to restore the statue alongside a counter monument “with equivalent presence and power, to really ignite a conversation, and to show opposition,” Ba says.

In fact, the Bristol-born street artist Banksy has put forward his own proposal on Instagram for how to deal with the monument, suggesting that it be reinstalled with the addition of bronze figures of protesters in the act of pulling him down. It’s a solution that works “for both those who miss the Colston statue and those who don’t,” Banksy wrote.

But artist Heather Phillipson, whose work is about to be installed on London’s Fourth Plinth, counters that it may be best for white artists to step aside.

“I think it’s time for white people to listen and make space,” she says. “And this may just be the perfect opportunity to, literally, do that.”

Shot of Ibrahim Mahama, “Silent Recreations,” © Mark Rietveld, courtesy Extra City.

Whatever solution is decided upon, how the decision gets made—and what lasting policy changes are put in place—is just as important as what the decisions are.

In 2018, curators Antonia Alampi and iLiana Fokianaki of Kunsthal Extra City in Antwerp worked with Ba and the artist Ibrahim Mahama to imagine a potential counter-monument to a local statue of the colonial missionary and explorer Constant de Deken standing with one of his knees on the back of an enslaved African person (people are now campaigning to remove this sculpture).

But the pair ended up resigning from their jobs a year into the project, saying that the museum had failed to implement serious anti-racist policies beyond its programming schedule.

The institution’s leaders had “no real understanding of the issues at stake” and changed nothing about their internal operations, the curators told Artnet News in a statement.

(In another incident in Antwerp, after authorities removed a sculpture of the brutal colonial-era ruler King Leopold II from a public space, the reason given was that the statue was damaged by protestors, implying no official condemnation of the monument’s subject.)

Alampi and Fokianaki say that now, with the momentum gathered by heated protests around the world, is the time for systemic change.

“We should aim to shape educational models and curricula, rename, unlearn, and listen to all those narratives that have been malevolently erased,” they said. “Otherwise, to be frank, it all is an empty symbolic gesture that whitewashes the real problems away and ultimately violently capitalizes on pain.”