Opinion

James Turrell Makes the Sky Look Like a Pantone Chip

THE DAILY PIC: At Pomona College, Turrell's Skyspace is so much about our senses, it proves that other art is all about thought.

THE DAILY PIC: At Pomona College, Turrell's Skyspace is so much about our senses, it proves that other art is all about thought.

Blake Gopnik

THE DAILY PIC (#1750): I’ve argued that the visual can be over-stressed in thinking about so-called “visual” art; non-visual or even anti-visual aspects can matter as much.

I’ve also argued that talking can matter at least as much as looking when it comes to taking in art. “Art is a machine for thinking” is a favorite saying of mine, meaning that art only comes alive when it is used as a trigger for new thoughts, not merely for new sensations. (I’d argue that the sensations only have meaning or impact when they are framed in thought.)

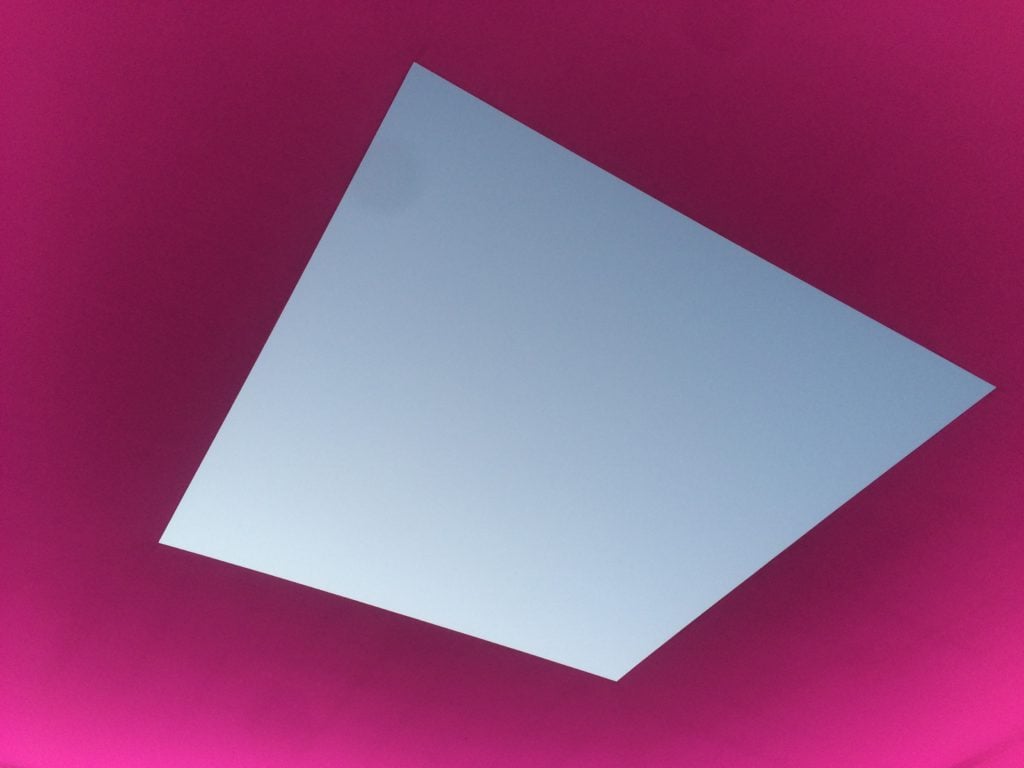

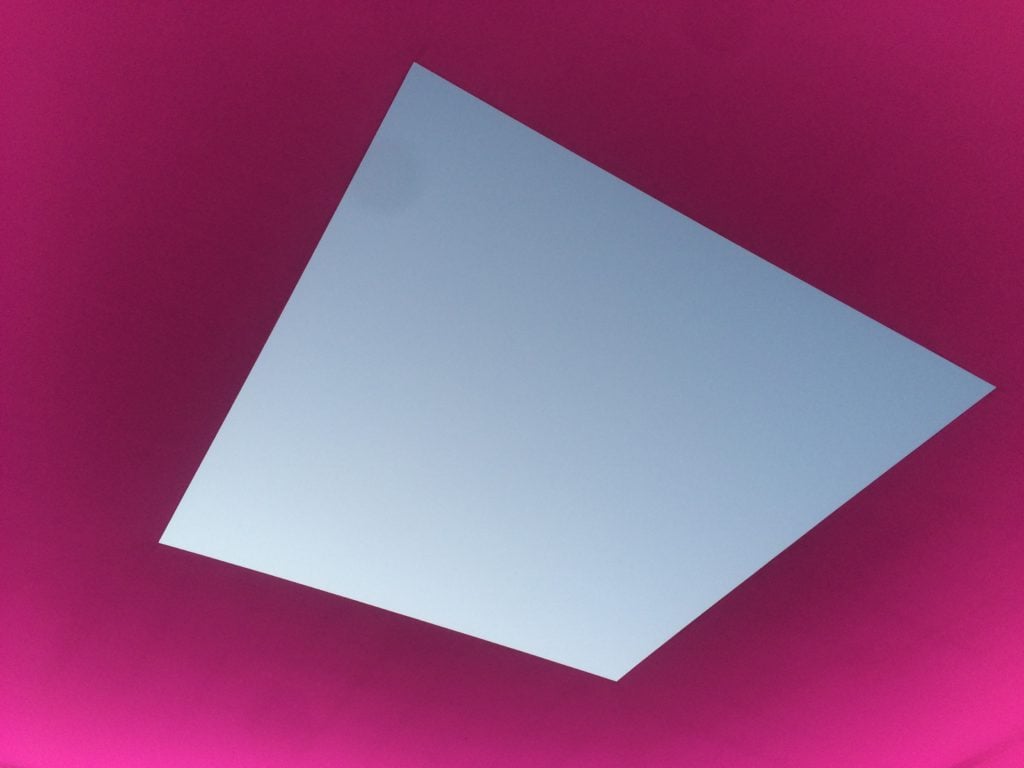

And then there are the distinctly sensory works of James Turrell, such as Dividing the Light, the recent Skyspace of his that I recently spent long spells with, over several days, at Pomona College in Claremont, California. Pomona’s Turrell consists of nothing more than a canopy perched over a courtyard, with a big square in the middle pierced through to the sky. The whole thing only comes alive every day at dawn and dusk, when for the space of something like 40 minutes variously colored lights play around the aperture’s edges, wreaking havoc with our normal sensations. There are times in Turrell’s installation when the sky truly seems to be an infinitely deep hole in space. (Which of course is just what it is.) Under other atmospheric and lighting conditions, the sky looks like it has been pasted onto the ceiling, or is floating like a patch of carpet just below or above it, woven in shades of pink or blue or gray. And that “carpet,” though perfectly square, can end up looking like all kinds of strange polygons—as per the image that I shot for today’s Daily Pic.

With its constantly changing effects, the Turrell encourages pure sensory absorption. You want to take in every subtle shift in what you are seeing and sensing; talk and reason just seem to get in the way.

Which, rather than negating my “cognitive” take on art, goes some way toward confirming it. It takes vast technological effort, after decades of experimentation, for Turrell to find a way to turn off our brains and tongues and get us to be pure creatures of sight. The sheer scale of that effort proves that the default condition for “visual” art is a much more conversational one.

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.