The University of Notre Dame in Indiana plans to cover up a series of 19th-century murals depicting Christopher Columbus after students, alumni, and employees said the works celebrated slavery and memorialized someone who “initiated one of the largest genocides in human history.”

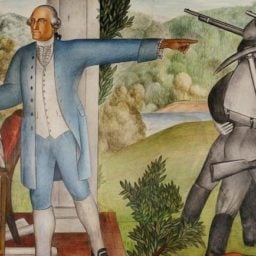

In a letter on Sunday, Reverend John Jenkins, the president of the university, said he would soon put in motion plans to remove from view the twelve murals tracing Columbus’s voyage to America. The works, by Italian artist Luigi Gregori, were created in the 1880s and adorn the inside of the university’s magnificent gold-domed main building.

In 2017, more than 340 students, faculty, and alumni signed a petition calling for the removal of the murals. They argued that the paintings misrepresent the reality of early American history by glorifying the European settlers while turning a blind eye to the plight of Native Americans.

The opposition coincided with a national discussion about what to do with public monuments and works of art that memorialized, and in some cases celebrated, America’s violent history. Among the objects ripe for debate in New York was the statue of Christopher Columbus next to Central Park. (Last year, the mayor decided to keep the statue in place and instead add a historical marker that more fully explained Columbus’s history.)

A mural of a priest blessing Christopher Columbus before he departed on his voyage. Photo: Robin Alam/Icon Sportswire via Getty Images.

The university initially told the Indianapolis Star in 2017 that it had no plans to remove the murals, which it said were commissioned to support members of the Catholic community at a time when Catholics faced discrimination. (The University of Notre Dame is a Catholic school).

Just over a year later, however, the university’s leadership has had a change of heart. In his letter, Jenkins acknowledged that the mural’s interpretation of events is now outdated. “The murals’ depiction of Columbus as beneficent explorer and friend of the native peoples hides from view the darker side of this story, a side we must acknowledge,” he wrote.

In response to earlier protests, the university began providing brochures in 1995 that offered a more complete account of the historical events depicted in the murals. But in recent years, advocates have noted that the brochures were not enough to counteract the works’ prominent placement.

The murals line the inside of the Main Administration Building at the University of Notre Dame. Photo: Robin Alam/Icon Sportswire via Getty Images.

Moving forward, the university will cover the murals with woven material. (Because they are frescoes, painted directly on the wet plaster, they cannot be removed without being permanently destroyed.) High-resolution images of the murals will be displayed elsewhere. Jenkins will assemble a committee to determine the location of the images and the contextual information provided in the display.

“We wish to preserve the artistic works originally intended to celebrate immigrant Catholics who were marginalized at the time in society, but do so in a way that avoids unintentionally marginalizing others,” Jenkins wrote.

The university’s Native American association welcomed the decision. In a Facebook post, the group wrote, “This is a good step towards acknowledging the full humanity of those Native people who have come before us.”