The Supreme Court’s unexpected decision against the Andy Warhol Foundation in Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith continues to be the talk of the town. Much has been written about it, and the legal questions are complex. Yet in terms of what kinds of arguments people make in public about fair use and appropriation art, I think the interesting question raised by the case—one that Sonia Sotomayor explicitly asks in her majority decision, but that gets less play in the commentary—is this: Do we actually believe, when it comes to “fair use,” in a “celebrity-artist exception?”

I’m not going to rehash all the details. Essentially, Vanity Fair paid to license a 1981 photo of Prince from Lynn Goldsmith on a single-use basis, hiring Andy Warhol to make an illustration of it for the magazine. Warhol went on to make a bunch of other artworks based on the picture in different color palettes. In 2016, when Prince died, Condé Nast used one of these alternate Princes as the cover of a special commemorative magazine called The Genius of Prince, paying the Warhol Foundation a lot of money to license it. Goldsmith thought she was owed something, and the lower courts couldn’t decide one way or another, so the Supreme Court decided, in a seven-two vote, that she was.

Important fair-use issues aside, part of the reason people are chattering about the case is how memorably rude justices Sotomayor (for the majority) and Elena Kagan (with John Roberts, for the minority) are to each other in their opinions. Here’s Sotomayor, rolling her eyes about the many pages of pedantic art-history gloss Kagan devotes to explaining the relation of Manet’s Olympia to Titian’s Venus of Urbino: “The Lives of the Artists undoubtedly makes for livelier reading than the U.S. Code or the U.S. Reports, but as a court, we do not have that luxury.”

And here’s Kagan, replying to what she sees as Sotomayor’s poor understanding of Warhol’s artistic process: “Ignoring reams of expert evidence—explaining, as every art historian could explain, exactly what the fuss is about—the majority plants itself firmly in the ‘I could paint that’ school of art criticism.”

Left: U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Elena Kagan at the George Washington University Law School, September 13, 2016 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images); right: Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor at George Washington University on March 01, 2019 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Paul Morigi/Getty Images)

Because the art world often trades in unique works that “comment” on the more pervasive popular culture, it instinctively assumes a defensively maximalist posture on appropriation (as opposed to the photography world, which has always been instinctively anti). And because Kagan’s dissent amounts to an extended defense of the value of Andy Warhol’s art, she has been seen as speaking for people who “get art.” Honestly, though, I think Kagan leaves out a major, obvious fact about this Warhol “Prince” artwork, thereby sidestepping the major creative questions at play.

And that is that it is a pretty bad Warhol. I actually think that’s important.

Is It (Good) Art?

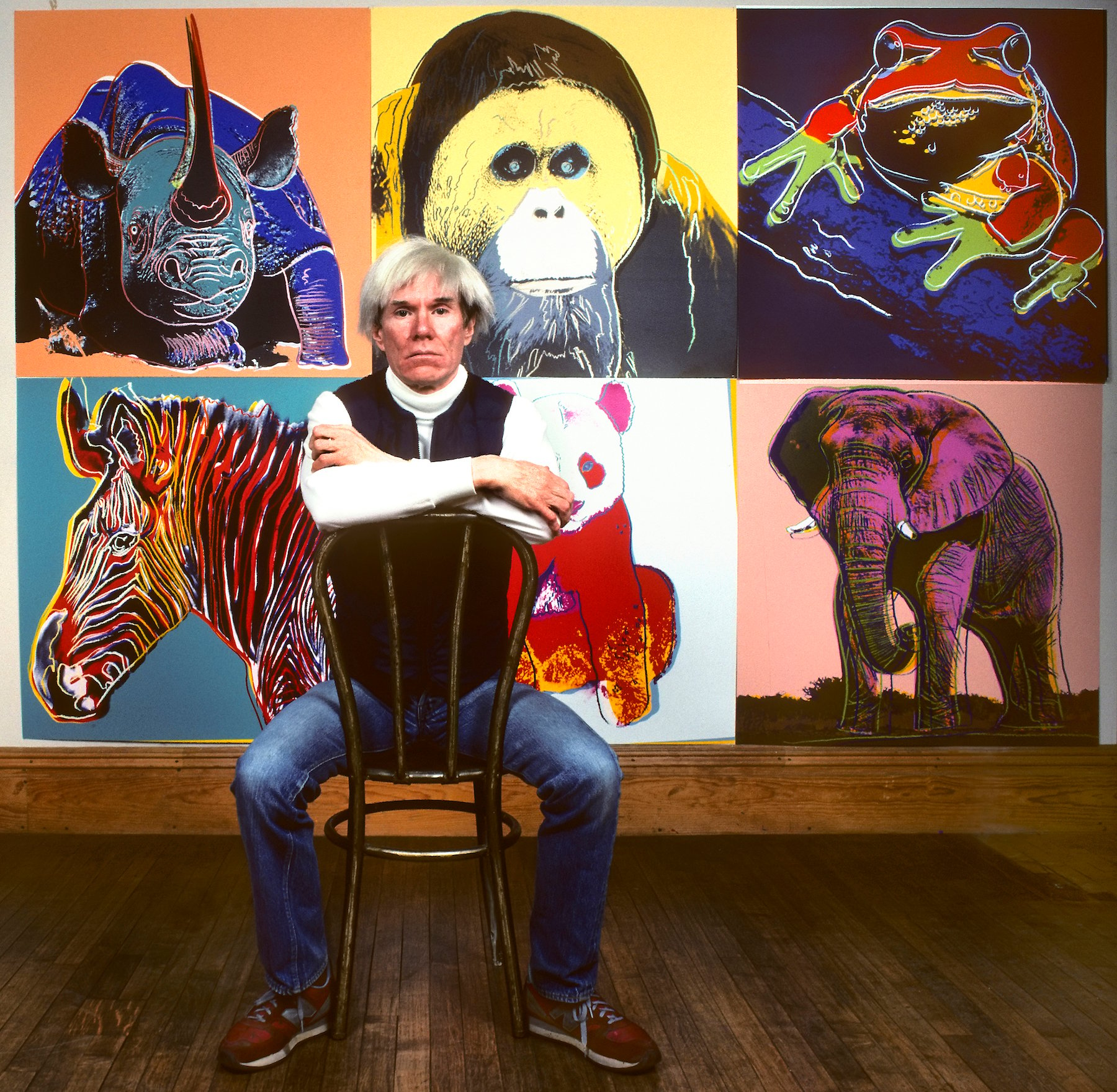

I mean, really, look at it. For the Pop art fans out there—do you truly think this “Prince” is Warhol working at the peak of his powers? Obviously not.

Kagan begins her text with an extended description of a totally different Warhol work, his much more famous Marilyn (1964). She describes in detail the process of creative transformation that went into taking a publicity photo and making it into the famous canvas known everywhere today. Kagan cites the idea of Marilyn as “a biting critique of the cult of celebrity, and the role it plays in American life.” She talks about the critical value of Warhol’s art: “He manifested, in short, the dehumanizing culture of celebrity in America.”

The 16 silkscreens and drawings in Andy Warhol’s “Prince Series,” based on Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of the musician, are the subject of a copyright lawsuit being heard by the U.S. Supreme Court. Courtesy of the Supreme Court of the United States.

And then Kagan simply says, “As with Marilyn, similarly with Prince.” The dissent will go on, over and over through its many pages, to say that Sotomayor and the other justices just don’t get the deep, critical take on the modern condition embedded in Warhol’s “Prince” series. She speaks of the “conveyance of new messages about celebrity culture and its personal and societal impacts” in his Prince canvases. She goes so far as to reference the “dazzling creativity in the Prince image.”

But, sorry, no. The Prince image is hack work. That is not an opinion of the “‘I could paint that’ school of art criticism”; it’s a common critical take on the late Warhol. The guy fell off as he got older.

The ‘60s Warhol of the the Marilyns and Jackies, the “Deaths and Disasters,” the “Thirteen Most Wanted,” Coca-Colas and Soup Cans—he’s witty and innovative here, using relatively low-fi means of silkscreen and artistic reframing, recoloring, and repetition to give a sense of distracted, channel-surfing glamour to the original images.

Andy Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn (1964) painting of Marilyn Monroe at Christie’s on March 21, 2022 in New York City. (Photo by Dia Dipasupil/Getty Images)

Late period Warhol is a different matter. There, he’s a bit adrift, living off of his previous glories to pay for his lavish lifestyle and many pet projects (e.g. Interview magazine). His “Society Portrait” era had his assistants churning out huge numbers Warhol-ized portraits at $25,000 a pop for any low-level celebrity or thirsty socialite who wanted one, as a money-making scheme. (He charged an additional $15,000 for extra panels.)

The 1984 Prince portrait was an even lower kind of hack work building on top of those mass-produced portraits, applying his by-then-signature style to a topical subject, to order. Kagan is appalled that the majority acts as if Warhol was just applying a Warhol “Instagram filter”—but that’s not too far from what he was doing in this case.

The Question of the Hack

Does it matter, though? Quality is subjective. Mediocre art has a right to exist too. And the late Warhol has its apologists. I just think that the magic of the name “Warhol” is clouding people’s perceptions of the kinds of arguments that need to be made about these particular works.

What if the name were “Mr. Brainwash” instead?

A decade ago, the much-loathed street artist lost a lawsuit for his appropriation of a famous 1977 photo of Sid Vicious, by Dennis Morris, the band’s photographer. The case was very similar. Brainwash made multiple Sid Vicious-based works he sold as part of his show “Life Is Beautiful,” doing different things to them—but at least one basically looked like the same photo, slightly recolored, but with a little paint thrown on it. The judge in that case said that “Most of the Defendants’ works add certain new elements, but the overall effect of each is not transformative” (similarly, Sotomayor cautions that the recent decision “does not mean that all of Warhol’s derivative works, nor all uses of them, give rise to the same fair use analysis.”)

In any case, Mr. Brainwash lost, but he tried to defend himself with exactly the same arguments about his work that Kagan imputes to Warhol’s “Prince”: that his color choices were meaningful and that the work was somehow “commentary on Sid Vicious’s persona and on the nature celebrity generally.” The judge noted that this appeared to be a “post-hoc rationalization,” and found unconvincing Brainwash’s defense that “no evidence about transformativeness was submitted prior to the reply because Defendants considered the transformative nature of the work self-evident.”

Essentially, the message was: If you are going to use the “fair use” defense to commercialize someone else’s copyrighted work, you have to at least pretend to try.

Mr. Brainwash at his first exhibition “Life is Beautiful” on June 17, 2008 at CBS Studios in Hollywood, California. (Photo by Paul Redmond/WireImage)

At that time, due to Mr. Brainwash’s rep as a high-test hack, few were sympathetic to him in the art world. (If you want to see just how low-effort appropriation art can be, go watch Mr. Brainwash’s assistants talk about his process in Exit Through the Gift Shop—it’s at about the hour mark.)

The question of lazy, un-creative uses of appropriation by powerful artists who are out of ideas and would like to coast on other people’s unique works is as important to address as the question of actual creative uses of appropriation!

Stressing the “Use” in Fair Use

And there’s a good chance that Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith would not even have affected the Brainwash case. The Court ducked the question of whether Warhol could make art out of Goldsmith’s photo (it “expresses no opinion as to the creation, display, or sale of the original Prince Series works”). It chose instead to focus on the novel-to-this-case question of licensing.

Commentators are lamenting the great chilling effect on creativity that this new Supreme Court ruling may create—and maybe that chill will come. We should be wary of unintended legal consequences (think of how invoking “art” has been used to legalize forms of anti-gay discrimination in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights).

Lynn Goldsmith poses for a photo with attorney Lisa Blatt on the steps of the Supreme Court for the Warhol v. Goldsmith case on October 12, 2022 in Washington, D.C. Photo by Mickey Osterreicher/Getty Images.

But Amy Adler goes so far as to write that, in the wake of the decision, “Any artist who works with existing imagery should now reconsider her practice.” I am not a legal scholar, but this seems… an extreme reaction.

Sotomayor’s reasoning is that the “use” of both a work and its appropriation are an important factor in determining how it is treated. In this very quirky case, Warhol’s Prince was created as work-for-hire illustration that required a specific photo, so that means that the derivatives of this particular work require special attention when they, too, are licensed as illustration for a very similar use.

As a lens to look at a complex problem with many edge cases, I find “use” actually more promising than Kagan’s seemingly boundless “isn’t all creativity copying?” line of argument, which leaves me wondering whether anyone even needed to license Goldsmith’s photo in the first place—as long as it was Andy Warhol who was using it.

A visitor views Brillo Box (1964) by Andy Warhol at the “Andy Warhol: Pop Art” exhibition at the RCB Galleria on August 12, 2020 in Bangkok, Thailand. (Photo by Jack Taylor/Getty Images)

Interestingly, although Kagan cites art critic and philosopher Arthur Danto on the second page of her dissent as an authority on the value of Warhol, I think Danto would agree that “use” is a key category. Danto’s entire philosophical argument, which emerged from his consideration of Warhol’s Brillo Boxes, was that the contextual “world” around an image is what made its meaning. The importance of visual transformation of the kind Kagan spends her time trying to vindicate in Warhol’s case was what he was arguing against, actually.

… And We Have to Talk About A.I. and Appropriation

Look, I’m not really equipped to elucidate the finer-grained legal questions. There really are unscrupulous people looking to exploit every angle. But to turn over all my cards, I think that the reason that I am more responsive to the majority here is that the topic of the hour is generative A.I. art.

Back when Warhol made his “Prince” series, he was doing promos for Amiga computers. Their most powerful art application was something called Deluxe Paint, the equivalent of carving images in stone tablets compared to now.

The subsequent decades of rapid technological transformation—prior to A.I.—already not only created an explosion of creative new forms of copying, but also eroded the potential for a stable creative career (something Astra Taylor explored in some passionate depth some time ago.) In the last 10 years, the realization has really set in that the maximalist “free culture is by definition good and progressive” position is not sustainable for most working creatives.

The new wave of generative A.I. is essentially a doomsday device crafted to demolish every form of stable protection for unique creative works. Trained on unthinkably huge amounts of often copyrighted materials, and capable of creative feats at speed, it sells the magical ability to target anything and remix it just enough so that you don’t need to worry about credit or compensation for any original labor, for whatever “use” you want.

It is very hard to regulate this technology. Still, the law is one of the only tools we might have to claw back shreds of value for original creators as every work of human creation is cheerfully dumped into the universal sausage grinder of Silicon Valley capital.

Tech companies were certainly watching Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith in advance. According to Bloomberg, they are now pondering what effects it might have for the A.I. generators. Of course, the actual decision to my eye seems deliberately specific—and so far not even the threat of humanity’s complete extermination has been enough to slow the corporate A.I. juggernaut. So I am not that optimistic about any meaningful change of course.

But reading the Kagan/Sotomayor back-and-forth has hit home to me that it’s not going to help the creative industries in navigating this perilous terrain if they remain completely attached to an automatic romanticization of Warhol-ian appropriation. It might actually be useful to think in a nuanced way about how the Warhol of 1964 is different than the Warhol of 1984 if we are going to find a way through the world of 2024.