Law & Politics

Did the Supreme Court’s Warhol Decision Further Complicate Copyright Law? Experts Weigh in on the Ruling’s Ramifications

Here's what to take away from the Supreme Court's ruling.

Here's what to take away from the Supreme Court's ruling.

Sarah Cascone

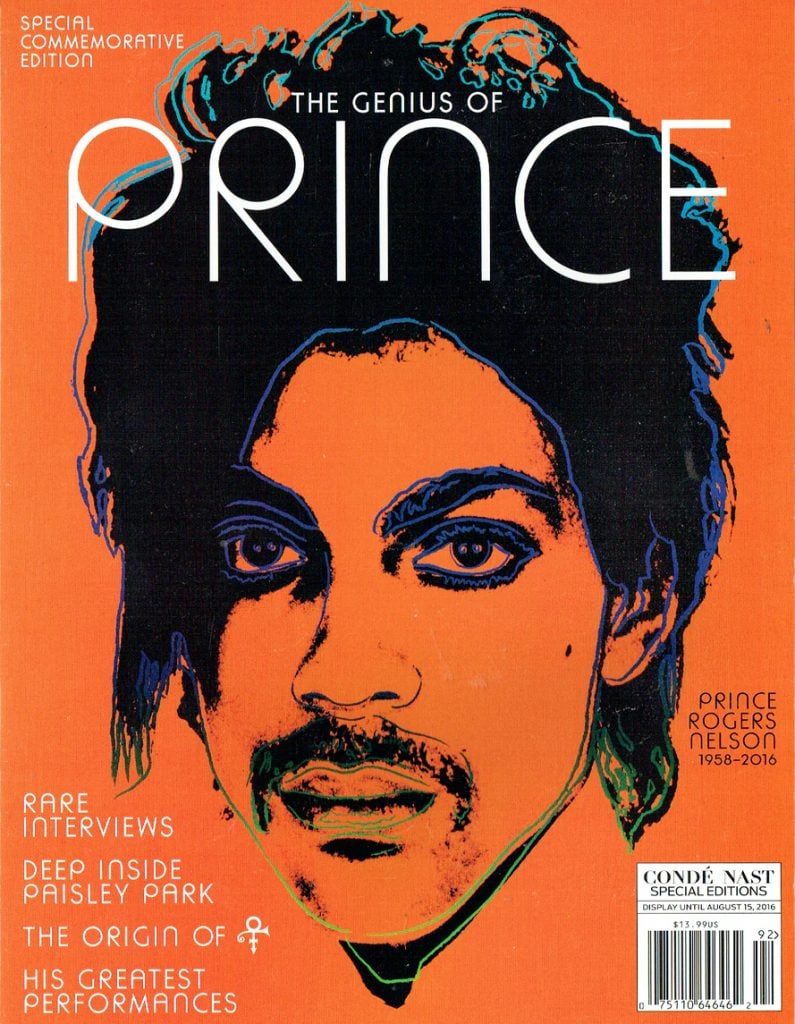

Last week, the Supreme Court handed down its long-awaited ruling in the case of Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith. The majority opinion found in favor of photographer Lynn Goldsmith that the Warhol Foundation infringed on her copyright when it licensed the Pop artist’s silkscreen portrait Orange Prince to Condé Nast in 2016.

Some legal experts are concerned about what the case means for art and creativity going forward. “It’s gonna stifle a lot of creativity,” Danielle Falls, a partner at First Gen Law told Artnet News. “A lot of art is going to be less risky and potentially less great than it otherwise would have been, absent this ruling.”

Other are declaring the court’s opinion a major victory for copyright protection, particularly for artists like Goldsmith, who make a living licensing their work for reproduction. “Contrary to the panic that may ensue following the issuance of the Supreme Court’s Warhol opinion, most creative artists should welcome the reining in of the copyright law’s fair use doctrine,” Gary Rinkerman, a partner of the firm Fisher Broyles, told Artnet News in an email.

Lynn Goldsmith poses for a photo with attorney Lisa Blatt on the steps of the Supreme Court for the Warhol v. Goldsmith case on October 12, 2022 in Washington, D.C. Photo: Mickey Osterreicher/Getty Images.

The ruling was the first Supreme Court decision to fully address copyright fair use doctrine since Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music Inc in 1994. As such, the closely watched case was always expected to have major ramifications for the doctrine of fair use under U.S. law, which applies a four-factor analysis to determine whether or not a secondary work is infringing.

In Campbell, which found 2 Live Crew’s parody cover of Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman” to be fair use, the deciding factor was the first one. That’s defined as “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes.”

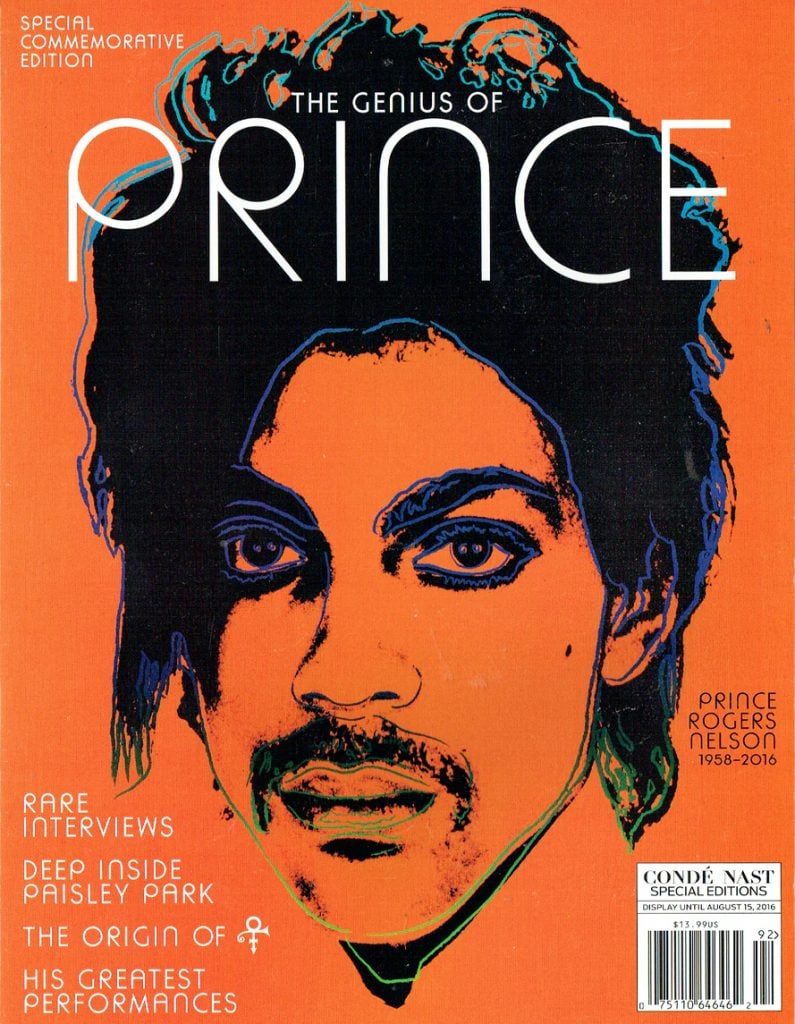

The court held that when the purpose of the use is transformative, the secondary work is fair use. That became the basis for the Second Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals’ 2013 ruling in Cariou v. Prince, which found that appropriation artist Richard Prince had been transformative in his 2008 “Canal Zone” series based on photographs by Patrick Cariou. Even though the works still had a shared aesthetic, the court found that Prince had imbued the images with new meaning.

It was that line of reasoning that saw the Warhol Foundation prevail in New York District Court in 2019. But the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed that ruling, taking issue with its assertion that Warhol transformed a photo of a “vulnerable, uncomfortable person” into “an iconic, larger-than-life figure.” The court warned that a “judge should not assume the role of art critic.”

Patrick Cariou’s original photograph and Richard Prince’s Graduation (2008).

Ahead of oral arguments at the Supreme Court, even Goldsmith’s advocates expected that transformation would weigh heavily on the decision, warning of the potential dangers of such a defense.

“By the foundation’s boundless theory,” Jeffrey Sedlik, the president and CEO of the Picture Licensing Universal System Coalition, wrote in an amicus brief for Goldsmith, “anyone can claim a transformative use—and thereby assert an essentially irrebuttable presumption of fair use—merely by claiming a change to the ‘meaning or message’ of a work.”

Had Warhol prevailed with its “extreme position on fair use,” Sedlik added, “it would have “pose[d] an existential threat to photographers.”

Sedlik’s position is that the court’s decision merely reinforces a long-established system by which photographers can license their work. “Artist reference licenses are widely available and easy to obtain,” he wrote.

The Supreme Court upheld the Court of Appeals decision. But, in a move that surprised some legal experts, the court’s latest opinion essentially does not discuss whether or not Andy Warhol’s Orange Prince was transformative of Goldsmith’s original portrait, focusing instead on the commercial use of both images.

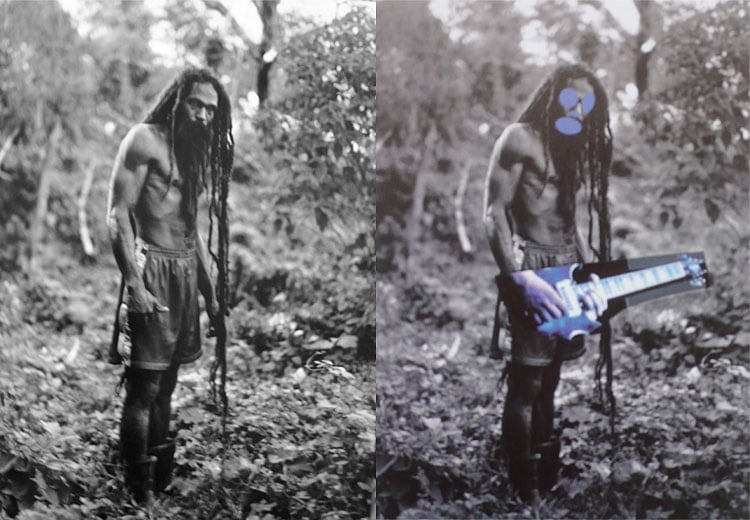

The 16 silkscreens and drawings in Andy Warhol’s “Prince Series,” based on Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of the musician, are the subject of a copyright lawsuit being heard by the U.S. Supreme Court. Courtesy of the Supreme Court of the United States.

“There was a lot of evidence in this case about how Warhol was doing something different from Lynn Goldsmith in his work. He was producing new message and meaning. And up until this decision, that would have counted a lot in favor of Warhol,” Amy Adler, a New York University law professor who helped write an amicus brief in support of the foundation, told Artnet News. “He may well still have lost, but that would have mattered. And this decision makes that matter less.”

Previously, the court had primarily limited analysis of the competing commercial use of two works to the fourth factor, which considers the secondary, derivative work’s impact on the market of the original.

“Now, when the first fair use factor is weighed, one of the things that will have to be considered is whether the use by the subsequent artist is serving as a commercial substitute for the original artist’s work,” Stephanie Bunting Glaser, a lawyer at Patterson Belknap, told Artnet News. “The court made it very clear that that’s important, notwithstanding how transformative that particular use is.”

“I’m reading the court’s new interpretation of that first factor as a narrowing of fair use more generally,” Adler added.

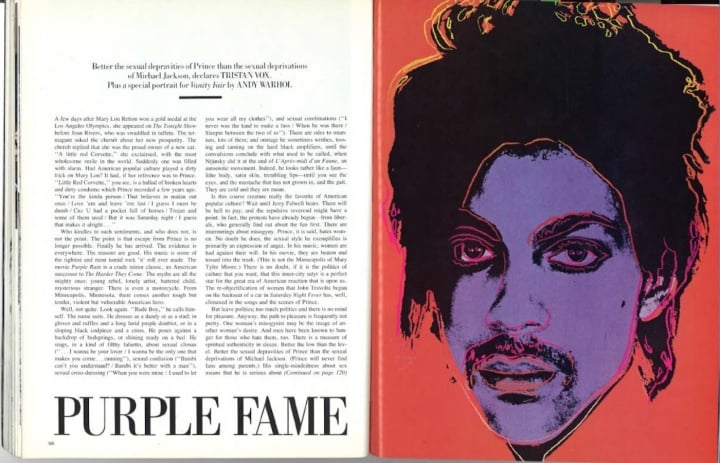

In 1984, Vanity Fair hired Warhol to illustrate an article about Prince. The magazine licensed Goldsmith’s 1981 photograph of the singer as an “artist reference” for $400. Warhol went on to make 16 different Prince artworks based on the image—even though the contract was for one-time use. (Four belong to the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh and the rest are in private collections.) When the publication published a second piece from the series after Prince’s death, it paid the foundation $10,000, but did not credit or compensate Goldsmith.

Lynn Goldsmith’s animated GIF of Andy Warhol’s screenprint superimposed over her photograph. Courtesy of Lynn Goldsmith.

What the majority opinion boiled down to was that the foundation licensed the Warhol artwork for use on the cover of a commemorative magazine paying tribute to the deceased musician. Because Goldsmith had done the same thing with her original photograph for People, the court decided that Warhol’s portrait had become a market substitute for the earlier work on which it was based.

“The bottom line is that Warhol’s work was admittedly substantially similar to photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s copyrighted photograph of Prince, the famous musician. Both works competed in the market for licensed images to illustrate biographical stories about Prince,” Rinkerman said. “This weighed against the ‘fair use’ defense asserted by the Warhol Foundation.”

The issue therefore, was the commercial licensing of the Warhol work—not necessarily the work itself.

“One of my big disappointments with the art world over the last 20 years, is that it’s turning into being more about money than it is about art,” Dean R. Nicyper, a partner at Withers, told Artnet News. “This opinion brings us out of the aesthetics and back to the money aspect of the art world.”

The court’s dissenting opinion, written by Justice Elena Kagan, with Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., also took issue with this approach.

“All of Warhol’s artistry and social commentary,” Kagan wrote, “is negated by one thing: Warhol licensed his portrait to a magazine, and Goldsmith sometimes licensed her photos to magazines too. That is the sum and substance of the majority opinion.”

But the majority may have found themselves painted into a corner because of the terms of Goldsmith’s initial licensing agreement.

“For Goldsmith to not get a license fee the second time around, that really smacks of unfairness,” Nicyper said. “So, in this very narrow context, I do think it’s appropriate that Goldsmith get a license fee. But I don’t know that it warrants re-altering the doctrine of transformativeness, considering the effect that might have on different uses of pre-existing works.”

Andy Warhol’s Prince illustration based on the Lynn Goldsmith photograph as it appeared in Vanity Fair, here reproduced in court documents.

Taking a different point of view, however, the Supreme Court’s decision can be viewed, Rinkerman wrote, “as reining in some of the recent excesses in U.S. copyright law’s fair use doctrine.”

In some ways, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, writing for the majority, seemed swayed by the David versus Goliath nature of the dispute between Goldsmith and the foundation. Here was a woman who succeeded against the odds as a rock photographer in a male-dominated industry, who the Warhol Foundation actually sued first when she dared to suggest Orange Prince infringed on the copyrighted photo on which it was based.

“There’s a strain of anti-elitism in the opinion,” Adler said. “Elitism should have no place in fair use, but there should be a place for considering whether artists are doing different things and creating new meanings in their work—because to the extent that they are, that furthers the goal of copyright, which is to promote creativity and new and innovation. In this effort to not favor the famous artist, which is in some ways laudable, the court lost sight of that goal.”

“One can discern a sympathy for Goldsmith, the working journalist, and a resentment of the Warhol Foundation, with its aura of art world glamor and privilege,” lawyer Marjorie Heins wrote in an op-ed for Artnet News. “The sympathy and the resentment are easy to understand, but they led the court’s seven-member majority into a legal quagmire and a disastrously wrong result.”

The decision noted that the court had “no opinion as to the creation, display, or sale of any of the original Prince Series works.” It also stated that Warhol’s famous “Campbell Soup Can” works are fair use, because they differ in purpose from the original imagery, which was used to advertised soup. A footnote even suggested that the Warhol Foundation might find itself back on the wrong side of fair use if it licensed the soup cans to a company selling soup.

It’s all undeniably confusing. In essence, the opinion seems to say that Orange Prince might have been a fair use creation—up until the moment the Warhol Foundation licensed it to appear in a magazine.

Lynn Goldsmith’s photo for a GoFundMe supporting her legal battle against the Andy Warhol Foundation. Photo courtesy of Lynn Goldsmith.

“The court’s analysis in this case suggests that, even when the creation of a new work—i.e., the initial copying—is fair use, the owner of the copyright in the original work always has a residual interest in the new work,” Jonathan Ellis of McGuire Woods told Artnet News in an email. “Every subsequent use of the new work must pass the fair-use test anew—without regard to the transformative nature of the work’s creation itself.

Kagan’s dissent also pointed out the mental gymnastics the opinion employed in its effort to explain why Warhol’s soup cans—which the court cited as an example of fair use in the 2021 case Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc.—weren’t infringing, but the Prince portrait was.

“Drawing a distinction between a ‘commentary on consumerism’—which is how the majority describes his soup canvases…—and a commentary on celebrity culture, i.e., the turning of people into consumption items, is slicing the baloney pretty thin,” Kagan wrote.

But fair use has always been a tricky can of worms.

“There isn’t all that much [in art] that one could argue is totally new,” Nicyper said. “Borrowing goes on all the time in music and art in all forms of art. It’s important that people don’t steal something wholesale. But I think there is value in allowing people to use what has gone before and to take it one step further.”

Now, that already tricky balancing act will become all the more challenging.

“This ruling has made it much more complicated. Artists who come to me for legal advice, in most cases, I would probably warn them that it’s just simply too dangerous to refer to pre-existing work,” Adler said. “There’s gonna be a lot more litigation trying to flesh out exactly what what this new interpretation means.”

More Trending Stories:

A Sculpture Depicting King Tut as a Black Man Is Sparking International Outrage