Opinion

The ‘Dissonant Chorus’ of the 2024 Whitney Biennial Lost Me

What do the politics of this show add up to?

What do the politics of this show add up to?

Danielle Jackson

With perhaps one idea too many, curators Meg Onli and Chrissie Iles have put together a Whitney Biennial this year that ultimately touches upon the news cycle, with A.I., trans experience, indigenous culture, and the right to abortion leading the pack. On the verge of a democracy-shaking election, “Even Better Than the Real Thing,” as the show is called, is rife with out-of-step, just-too-late curatorial activism and occasional editorial overreach. I found much of the show to be at loose ends; each topic is atomized, and every person is on their own. The show’s voice, if there is one, veers from a deeply engaged pedagogical project of educating the world on a range of cultures to a darkly insular, standoffish retreat. The net effect felt like a diffuse, nonspecific, yet cloistered approach to the otherwise rich topics of disease, world politics, and gender. To appropriate a bit of dialogue from a film in the show by Ligia Lewis: “You may wonder how these disparate parts go together? Well, they do and they don’t.”

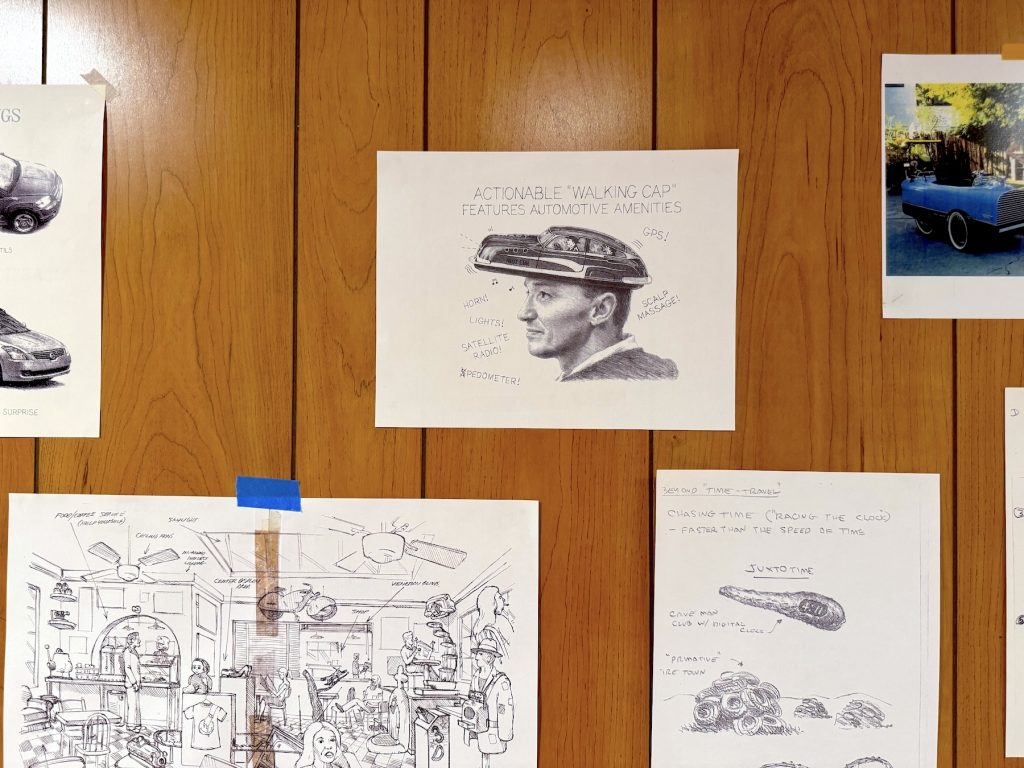

Can it even all come together? A number of the exhibition’s themes—technology, the body, pastiche, aging, and invention—appear succinctly in the installation of sketches by Pippa Garner on the third floor. Garner’s truncated version of Inventor’s Office is a collection of notes, clippings, and memos detailing wry and useless prototypes for products in a sendup of the home-shopping catalogue. The installation, mounted towards the end of a year of retrospective books and exhibitions honoring the 82-year-old artist, is a nod to Garner’s decades-long practice of experimentation that ranges from the world of consumer goods to the artist’s personal expression of gender. Some of these sketches had been seen before so I went in knowing what I was getting. In the end I was glad that it had been included—on balance, it’s one of the few works that added levity.

Detail of Pippa Garner, Inventor’s Office (2021). Photo by Ben Davis.

Another work that ties together a number of themes is Nikita Gale’s spirited Tempo Rubato (Stolen Time), which takes the form of a player piano. Spot-lit, the instrument plays alone in a gallery. Ivory keys have been replaced by wood, producing a sound, to my ears, akin to tap shoes on floorboards. A rhythm of muted notes vibrates throughout the room (it’s one of a few works which buzz and hum throughout the exhibition.) To me, Tempo Rubato brought to mind questions about artificial intelligence. The player piano is a familiar example within intellectual property law and its use is even a bit on the nose as an example of the “ghost in the machine.” Yet, the sight of this bygone technology made anew, the sound of muffled syncopation, and the score reminiscent of a Scott Joplin rag, invited allusion to murky questions of love and theft, copy and original, that mark the multicultural origins of American musical performance.

That reading of Gale’s work bridges to what, for me, is the core takeaway of the 2024 Whitney Biennial: the tenuous standing of our imagined coalitions. This biennial, more than others, called to mind the potential isolation of pluralism. Onli and Iles devote attention to “marginalized people,” defined here as a loose collection of women, people of color, the sick and disabled, and trans folk. But don’t mistake this for a cohort; the idea of coalition is very lightly worn. Just who is oppressing whom is never named, but with such a mix—what the curators call a “dissonant chorus”—the threats could come from anywhere (Right-wing evangelicals? Left-wing activists? Figurative painters?). Few white artists are included in the exhibition—a decision with ill-considered and potentially far-reaching implications—but white influences are mentioned explicitly in some captions as forces to evade. Interest in others, much less reliance on them, felt in short supply. I sensed few commitments beyond those made to the most immediate of circles.

Installation view of Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich, Too Bright to See (2023-24). Photo by Ben Davis

Instead, the artists tend toward small groups and small spaces. Forms of handicraft such as crocheted lace and handmade quilts by ektor garcia and Harmony Hammond, respectively, recall the safety and familiarity of the private sphere. Weaving and pottery in Clarissa Tossin’s video Mojo’q che b’ixan ri ixkanulab’/Antes de que los volcanes canten/Before the Volcanoes Sing esteem a close-knit traditional order.

Alienation, loneliness, and yearning pervade: in Madeline Hunt-Ehrlich’s gorgeous film on writer Suzanne Césaire, in Constantina Zavritsanos’s projection of frenzied messages, and in Maja Ruznic’s paintings inspired by her memories as a Bosnian refugee. Throughout the exhibition I saw artists scrambling for ways to put scattered pieces together. Sharon Hayes’s video Richerche, four is a meditation on finally finding one’s people. Inspired by Pasolini’s man-on-the-street interviews in his film Love Meetings (1963), Hayes records the thoughts of gay, lesbian, and gender nonconforming people in advanced age (some bristled at the term “queer elders”). Filmed with groups in Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and the tiny Dowelltown, Tennessee (pop. 357) the subjects appear to be reacting to each other in one giant gathering, but the cohesive picture is merely an illusion. The installation extends the world of the film (and the dream of unity) with a circle of mismatched chairs where viewers are invited to watch as would-be members of the group.

Sharon Hayes, Ricerche: four (2024). Photo by Ben Davis.

The exhibition in places seems loosely organized by theme, which is to say, due to the subjects of the work, it’s also organized by constituencies—there’s the women’s quarter (Carmen Winant, Julia Phillips, Harmony Hammond); a gallery for the aged, ill, and infirm (Hayes, Carolyn Lazard, Mary Kelly); an area for the Black Atlantic (Isaac Julien, Dionne Lee, Mary Lovelace O’Neal); and a zone for work on cosmologies of Indigenous peoples (Clarissa Tossin, Rose B. Simpson, Eamon Ore-Giron). Large works from transgender perspectives are literally “centered” on three of the exhibition’s floors. These types of hanging invite viewers to read the works first and foremost through an essentialist lens and to read artists as emissaries of discrete interest groups. It unintentionally reproduces the old colonial districts, producing an experience not unlike the World’s Fair.

Julia Phillips, Nourisher (2022) in the Whitney Biennial 2024. Photo by Ben Davis.

The texts offer some of the most extraordinary examples of editorial overreach. The captions go out of their way to foreground cultural experience in ways that seem sometimes at odds with the artist’s own ideas and provide a tendentious overlay of racialized context where there may be none. For example, German-born Julia Phillips has described her ceramic sculpture, Nourisher, as the result of very personal, nuanced, and sensitive perceptions on motherhood and breast-feeding. In the audio guide, however, Onli relates the work to the history of medical experimentation on Black women.

Installation view of Dionne Lee, Challenger Deep (2019). Photo by Ben Davis.

Likewise, the text for Dionne Lee’s Challenger Deep, an otherwise chill video on the ancient and mystical practice of water dowsing, claims the work rejects colonial landscape imagery in favor of “Black experiences of survival and the land.” (To my eye, the video resembles the view characteristic of a violent first-person-shooter video game). Dowsing, or water-witching, has been practiced throughout Europe for hundreds of years and is continued as pressures to locate clean water and natural environments rise everywhere. The way in which Challenger Deep contextualizes it as proprietary is a missed opportunity.

Installation view of Isaac Julien, Once Again… (Statues Never Die) (2022) at the Whitney Biennial. Photo by Ben Davis.

I am inspired by the premise of video installations that call attention to forgotten cultural figures and historical events. The results are very mixed, often hectoring and didactic, and occasionally veer into hagiography, but I still believe the endeavor is worthwhile. Curiously, a few of these installations place traditional forms in venues of high culture: in Tossin, a Maya flute is played in a concert hall; in Lewis, we see a Dominican reverie among the conifers in Rimini, Italy; in Julien, West African statuary appear in the hallowed grounds of a private university. Does this say something about the role of the artists in the exhibition itself?

Despite such complexity, a major section of the show is a reflection of the ways a lot of people have learned to talk about identity—by sharing familiar symbols or reading soundbites in tiny bubbles on the Internet, and through a scrim of tumblr politics. Frequently iconicized transgender activist Marsha P. Johnson appears more than once, as do distressed American flags. Demian DinéYazhi’s neon work encapsulates much of today’s social justice statement politics, flickering the message we must stop imagining destruction + extraction + deforestation + cages + torture + displacement + surveillance + genocide! We must pursue + predict + imagine routes towards liberation! (it also features the discretely hidden message “free Palestine”). This is the abstract language of activist “visioning,” where power is the stuff of dreams, one declares rather than strategizes, and the work of governing is staved off and left to someone else.

P. Staff, Afferent Nerves (2023) and À Travers Le Mal (2023). Photo by Ben Davis.

If you start on the sixth floor, you will first encounter P. Staff’s Afferent Nerves, a canopy of electrified wires meant to simulate the nervous system, and A Travers Le Mal, a blown-up photograph of the artist in bed, hands over face, “in a gesture suggesting suffering or retreat.” In medicine, the afferent nerve goes inward, and joining this idea with Staff’s refusal, one may glean an implicit strand of politics underscoring part of the show. If, as I noted in these pages, the 2019 Whitney Biennial was marked by contentment with “being in the room,” this year’s crop of artists has a much more ambiguous and negative stance towards the prospect of ever taking outright command. Call it “rest as resistance,” a resurgence of “queer negativity,” “radical passivity,” “hanging out,” or “black fugitivity”—there’s almost no will to power. The exhibition reflects any number of popular academic theories of “unbelonging” and non-participation which appear self-sustaining but, in aggregate, can be anti-political. This disinterested relationship to power may be read as resulting from the incessant attacks on rights and personhood, but the biennial suggests a worrying number of defeated cultures who have returned to their camps to tend to their wounds.

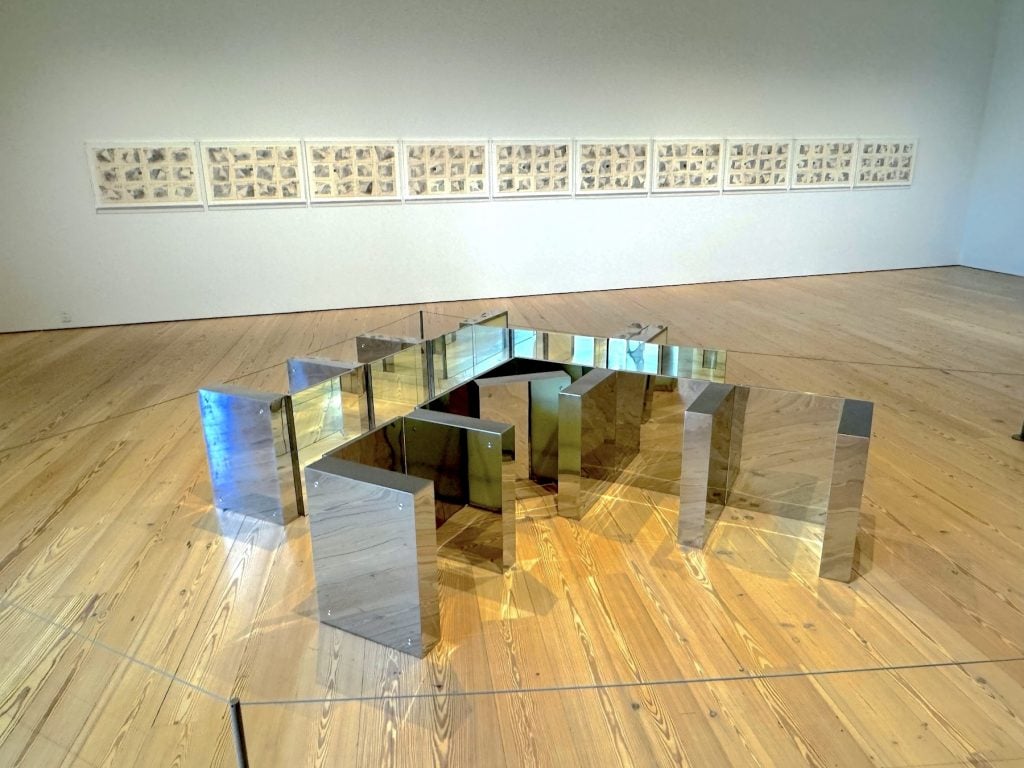

By extension, perhaps, there are a number of works that address illness and disability. Given its association with malingering, sham doctors, and an embrace of alternative health, chronic illness as both a medical category and a vector of identity is a domain where the concept of “the real” is readily contested. The defensive, self-protective position many people have taken towards their diagnoses has changed the way in which being sick is now imagined and also has led to occasionally inscrutable artworks on disease. Perhaps none better depict this insularity than Carolyn Lazard’s Toilette. An arrangement of medicine cabinets—the mirrored kind—face each other in private conversation, like a walled-off topiary garden. The cabinet doors open to reveal what looks like an opaque plexiglas that blurs the sight of the shelves inside. The caption indicates the cabinets are filled with Vaseline, and the symbolism of this material as both beneficial wound healer and harmful petrochemical is doing heavy metaphorical work in spite of the fact it’s hard to even perceive its presence. Historically, Vaseline has been a beloved beauty product in Black households which adds another layer of meaning for only a knowing audience. Lazard’s advocacy as a member of the collective Canaries once pictured the status of the ill as a warning sign to the broader society, a position I once found generous and wise. Today Lazard is interested in “collective forms of care,” but the literal inward-facing quality of this work seems to address very few. There are many people who can relate to the ideas of rest, overwork, and the need for mutual aid, but instead of unifying, illness in this exhibition has been reclaimed as a unique and special status, even in the wake of a world-altering pandemic.

Carolyn Lazard, Toilette (2024), with Mary Kelly, Lacunae (2023) in the background. Photo by Ben Davis.

I worry that the exhibition reflects a larger phenomenon of cultural gerrymandering in American public life. Thanks to a wildly decentralized media ecology, narrow slices of the population can garner outsized attention without depending on the support of others. A similar logic arose in activist spaces during the last few years to suggest that “high tides will float all boats,” that by centering the concerns of the “most vulnerable” all else will benefit without the need for cooperation. This can create a hands-off approach to progress. If I don’t do something, somebody else will.

In the catalogue, the curators describe the 2024 exhibition as commemorating the 30th anniversary of the “1993 Biennial Exhibition,” the infamous “identity politics” show. Yet there are other events from thirty-some years ago that are worth remembering besides the ‘93 Biennial, namely, the era’s transformation of long-standing alliances including the stunning collapse of the multiethnic Yugoslavia into conflict and the hard-won birth of the “rainbow nation” in South Africa (now faltered). Also thirty years ago, Nancy Fraser identified the struggle for cultural recognition as the ascendant idea of justice, displacing struggles over material redistribution. She posed the question of whether racial, sexual, and other minorities might be able to develop effective new forms of collectivity with so many contradictory goals. These references point to another reading of Onli and Iles’s “dissonant chorus”: American art, often behind the curve on how people actually live together, functioning as no more than a series of Bantustans, bands of outsiders never quite coalescing, never giving up ground.

Installation view of work by Ser Serpas. Photo by Ben Davis.

The curators have retraced the themes of the ‘93 show very closely in this biennial, though the effects differ. The 1993 biennial, for its part, was nakedly skeptical of identity borders and cultural authority. In some ways, the ‘93 exhibition actually paved the way for a mix of post-essentialist positions including the brief but ideologically vital Post-Black project and the widespread discussion of gender fluidity. The ‘93 catalogue openly addresses the conflict of broaching universality while making group claims to uniqueness. The 2024 presentation on the other hand appears to have doubled down on group boundaries by keeping everyone among their “own” to speak for their clan. The ‘93 show also had its share of what was then branded “the pathetic aesthetic” or “the art of failure,” works that embraced a certain powerlessness owing to marginality. In 2024, the difference is that inward tendencies are used by artists who are giving up (or appearing to turn from others) just as they are poised to take the mantle.

The artists in the 1993 biennial—children of the 1950s and 1960s—were pushing back against the concept of cultural homogeneity and resisted their position as “subaltern”; for the duration of their lives they belonged to groups that lacked much discernible power. This year’s collection of artists, born mostly in the 1980s and 1990s, seem to adopt the same posture despite their potential to actually inherit that power due to radical demographic change, a politic of those who, as in the famous slogan from an artwork by ‘93 Biennial artist Daniel J. Martinez, can’t imagine ever wanting to be white, and instead have resigned themselves to talking shit and punching up.

Installation view of Eamon Ore-Giron, Talking Shit With my Jaguar Face (2024) and Talking Shit With Amaru (Wari) (2023). Photo by Ben Davis.

Since 2011 slightly more than half of all American babies have been “nonwhite” and I imagine those kids will be filtering into art school very soon. Thirty years from now, will we still be seeing this kind of work on power and history from the position of the underdog? Can we steer them, or will they steer us, towards a different set of questions? I do not take issue with the topic of grievance, but I asked myself, while looking at a pile of crumpled refuse, what else is there? By the end of the exhibition I felt confined and exhausted by the small worlds of this show’s identity politics. Sometimes in order to “take up space,” one needs to stretch out.

In 2019, I wrote about the biennial and what I felt to be the presence of the “majority-minority” growing comfortable with a seat at the table. I know now I was mistaken to automatically ascribe power to members of this patchwork demographic. Majorities, however they are formed, can remain disenfranchised when they don’t hang together. The working class has long been so divided, and women, of course, number slightly more than half of the U.S. population and their interests couldn’t be more splintered. The majority-minority bloc I wrote about then, and see today on view, is both fact and fiction, a statistic and a construct. And its “power”—psychic, social, and political—is only as real as the willingness to make something of it.

“Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing” is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, through August 11, 2024.