Raised between Los Angeles and Mazatlán, Mexico before eventually settling in Guadalajara, multidisciplinary artist Eduardo Sarabia has achieved international acclaim for his work examining the economic forces at play in northern Mexico, and their impact on its traditions. His paintings, sculptural objects, and installations combine ceramic tiles, glass, and hand-woven textiles—materials typically used by local craftspeople.

Likewise, the Mexico City–based Orly Anan touches on themes integral to Mexican culture in her work. Since her formative years studying theater and scenography in Tel Aviv, the Colombian-Israeli artist has become known for transforming spaces into otherworldly environments—and she was commissioned by Maestro Dobel to create a series of works for The Fruit Chemist, its inaugural Maestro Dobel Artpothecary project, at Frieze New York earlier this year.

Maestro Dobel Tequila also supported Sarabia’s large-scale, site-specific The Passenger installation at Desert X in California’s Coachella Valley. Meeting for the first time, the artists spoke with Artnet News about their paths to Mexico, their shared interests in local narratives, and (yes) tequila.

Orly Anan (photo: Camila Falquez) and Eduardo Sarabia (courtesy of the artist).

For each of you, what is the story behind your decision to pursue a career in the arts?

Eduardo Sarabia (E.S.): I think I was five or six. The teacher noticed that I drew really well, and she convinced my parents that I should attend after-school art classes. It was a good way to keep me out of trouble.

And then I won a prize to study painting in Leningrad [now St. Petersburg] in Russia—the Soviet Union [at that time]. I was 12 or 13. I went there for four months, and when I came back, I told my parents, “If I can travel and do what I love, this is what I want to do.”

So I went to an arts-focused high school in Los Angeles. I felt early on that I could survive making work and doing shows. Obviously it’s hard, but [you have to be] a bit stubborn with what you’re doing. I’ve definitely had many distractions, [but] it’s something I was passionate about and still am. I’ve been very lucky.

Orly Anan (O.A.): Eduardo, I’m a huge fan of your work. I absolutely love it.

I can very much identify with everything you said. Because, for me, it was also from a really young age—maybe five years old—that I was always getting dressed up and making performances. When I moved to Israel and it came time to study, we could choose our specialty, but I wasn’t good at painting or at doing anything with my hands. I’m still not good at it.

But I knew I had ideas. I was always dreaming about creating different worlds. So I started to do theater, producing set designs for students. I started falling in love with the idea that we all have the power to transform spaces [in order] to travel to different moments in life, into the future or the past.

Right now, I am speaking to you from my studio, which is basically like a 3D collage, all the time.

A sculptural work by Eduardo Sarabia. Courtesy of the artist.

What drew each of you to work in Mexico?

E.S.: My family is from Mexico, and I grew up between Mazatlán and Los Angeles. [Between] LA street culture [and] being very Mexican in the home—plus I spent all my summers in Mazatlán—the culture was and [still] is a big influence on my work.

After I graduated [from art school in Los Angeles], I planned to go to Berlin. But right before I was to go, [I got a call from] the collector José Noé Suro Salceda, who owns the Cerámica Suro ceramic factory in Guadalajara. He invited me to come and produce something. I’d never been to Guadalajara.

I came here for the first time and it opened up a lot of possibilities. You know, in Los Angeles, to produce the work that I was interested in making—very theatrical and sculptural—it was expensive. For this guy to be like, “Come to my factory; do whatever you want; don’t worry about costs; just go crazy”—it was exciting.

So, this month-long trip turned into what is now almost 20 years of me being here. My gosh.

I did make it to Berlin, where I opened a tequila bar, and I went back and forth for about seven years. And then I decided to make Guadalajara my home. Everything is happening here—all of the narratives that are a huge part of my work. So it’s a great place for me to research and develop and produce.

Eduardo Sarabia, Eternal Dance. Courtesy of the artist.

O.A.: It’s amazing that you’re talking about that tile and ceramic factory in Guadalajara. Just last night, I was having a long conversation with an architect friend; I want to start custom-making objects, and he told me about José Noé Suro Salceda. I love the quality of your work, so I’m sure the factory is amazing.

Regarding Mexico and me, I know it’s a super-cliche, but as a teen, I had a Frida Kahlo book in my mom’s house. I read what is now the classic phrase: “Pies para qué los quiero si tengo alas para volar?” (which translates roughly to “Feet, what do I need them for if I have wings to fly?”).

And it just opened something for me. I started to become very obsessed with Mexico. For the seven years I lived in New York, I refused to go [there], because I always thought, “The day I put one foot in Mexico, I know I’m going to stay.”

And that is exactly what happened. I came to see a friend who had moved to Mexico City, and she introduced me to some galleries, even though I wasn’t even taking myself seriously as an artist. I was doing, like, little video shoots of myself that were very experimental and not good quality. A gallerist asked me to show him what I do, and I said, “I don’t know what I do!”

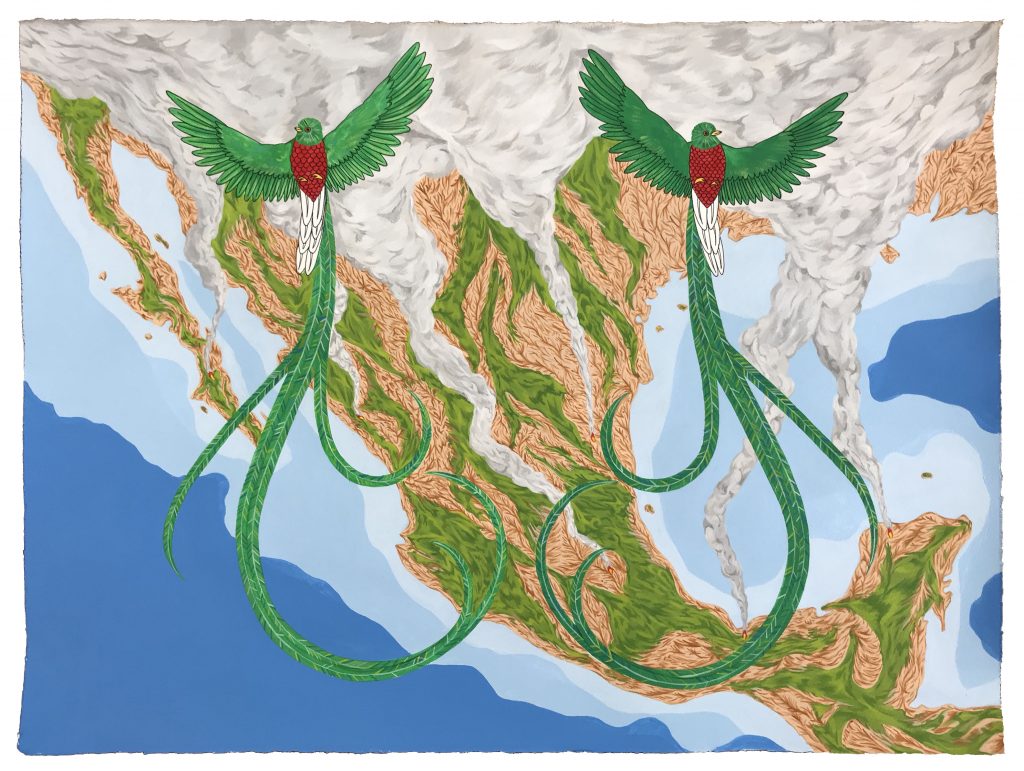

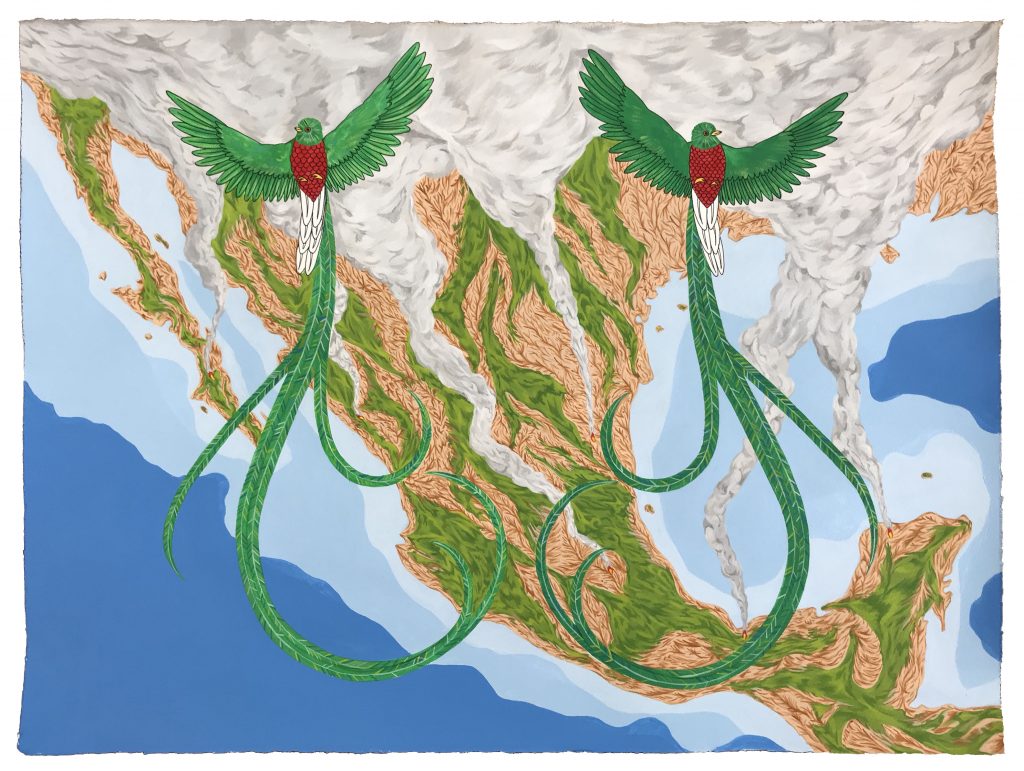

The Fruit Chemist, a Maestro Dobel Artpothecary project. Courtesy of Orly Anan for Maestro Dobel Tequila.

But he insisted, and after he saw it, he said, “Okay, you’re coming to the gallery tomorrow and I want you to do a solo show.” I didn’t believe him—I thought, you know, we’re drinking, we’re in a loud restaurant. But then it actually took place. So I came for three months to explore the culture for real, not to just stay with the romantic idea of what Mexico means for me as a Latin-American woman.

[Everywhere you go in Mexico,] you bump into a different ritual, custom, food, color, flower. I was just like, “Get it inside of me.” This is my favorite [place] on Earth. Everything collides [and] I can just absorb [it all].

Before moving, I was very afraid. I thought I’d be too poor to even buy beans, and I was thinking, “I’m going to give up on this life in New York to take a chance.” But the total opposite was true. Mexico [is] so abundant. I’ve been meeting so many creative, amazing people. Everything is so alive: ritual, dancing, animals. And it’s so resourceful [in terms of] materials.

As you were saying [Eduardo], anything is possible here. Even if it doesn’t yet exist, we make it happen. It’s a feeling of infinite possibilities.

As an artist, there’s always this fear: “Oh, you’re giving up on Europe or the U.S., where you have to live to be successful.” No—you should live where you feel inspired, and where you have access to everything you need to make your art. And then all the rest will follow.

E.S.: For sure. Things happen all over Mexico. After being here 20 years, I’m not really feeling like I’m missing out by not being in New York or Berlin or Europe in general. I definitely get a lot of calls from friends, asking, “What are you still doing there?” But Orly, like you said, this is where I’m inspired and where the creativity happens.

The Fruit Chemist, a Maestro Dobel Artpothecary project. Courtesy of Orly Anan for Maestro Dobel Tequila.

Both of you worked on projects under Maestro Dobel Artpothecary this year—Orly, yours inaugurated the platform at Frieze New York, and Eduardo, yours was staged at Desert X in California. What was it like working with the brand to bring your art to life?

O.A.: It was a really amazing experience because I [could] just be myself, and that’s the best [as] an artist—when they let you be free. [No one] stopped me from [doing] what I wanted to do.

I also feel very [connected] with their process [of making] tequila—how artisanal it is, and the ritual that goes into the creation of each bottle.

E.S.: When I first came to Mexico, I did a lot of projects around spirits and distilled alcohol. I loved doing [that] research, and I love working with people who connect with artisans and tradition [while] trying to support contemporary culture.

The installation I did in the desert had to do with migration. I like working with artisans and communities here in Mexico. In this case, I worked with weavers to tell their story and make it feel like a collaboration, not an appropriation.

It was a great experience. I think once it was all done, we had about 650,000 visitors, which—wow. The project was well-received, and just [because of] the personal, small stories that I was able to share [it] was very, very exciting. I’m grateful to have had a collaboration like that.