Susan Herbert. Photo: courtesy of the artist/ Thames & Hudson.

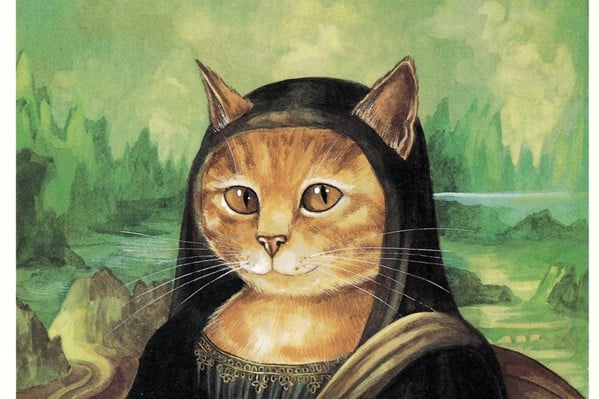

“The smallest feline is a masterpiece,” wrote Leonardo da Vinci, whose drawing Study of Cat Movements and Positions testifies to his admiration for the animal’s flexibility; Thomas Gainsborough‘s and Paul Gauguin‘s cat studies were very similar to da Vinci’s.

Cats have proliferated in art over the centuries. They became particularly popular as the cuddly familiars of females in paintings by Victorian artists and French Impressionists.

The cat painted by Edouard Manet in the lap of his eight-year-old niece Julie (the daughter of Berthe Morisot, herself a future artist) in 1887 may be the most content in art history. Less reassuring is the black cat—symbol of prostitution—perched on the end of the naked woman’s bed in Manet’s Olympia, which scandalized Paris when it was shown at the 1865 Salon.

As the art and literature scholar Bram Dijkstra has observed, cats and female sexuality became sinisterly symbiotic in a strain of misogynistic fin de siècle art prompted by male fears and inadequacies. The thinly veiled symbolism of paintings by Charles J. Chaplin, Franz von Lembach, Hans Makart, and others inferred that women are not only insatiable but prone to bestiality.

Comparatively benign are the fighting cats painted by Goya and John James Audubon, Picasso‘s Cat Catching a Bird, Robert Crumb‘s rutting Fritz the Cat, and the colorful subjects of Andy Warhol’s privately printed 1954 book 25 Cats Named Sam and One Blue Pussy.

The list that follows is not a canonical Top 10 of cat paintings, but a tribute to feline diversity in art.

Hieronymous Bosch, The Temptation of St. Anthony (right panel) (circa 1501).

In the wilderness, a cat hisses at the woman who’s trying to tempt the hermit Anthony, father of monasticism, with her naked body. The fish symbolized Christianity, but the cat’s demonic ears render it ambiguous.

Théodule-Augustin Ribot, The Cook and the Cat (1860s).

Another fish, another hungry cat. The French realist Ribot made his name painting humble kitchen scenes, of which this is the most famous. Is the cook oblivious to his four-legged friend, or is he turning a blind eye?

Louis Wain, anthropomorphic cat paintings.

A popular London commercial artist obsessed with cats, Wain was permanently hospitalized for mental illness in 1924. That his paintings became increasingly hallucinatory and abstract has been attributed to worsening schizophrenia.

Jeff Koons, Cat on a Clothesline (1994–2001).

Inspired by postcards of kittens suspended in socks, Koons sculpted his outsized polyethylene puss for his “Celebration” series. It was structured as a crucifixion to combine spirituality with preschool joyousness.

Arthur Rackham, By day she made herself into a cat (1920).

This malevolent “she” is a shape-shifting witch who turns virgins into birds and cages them. Rackham’s illustration for “Jorinde and Joringel” in Hansel and Gretel and Other Tales by the Brothers Grimm demonstrates his brilliant use of anthropomorphism to capture pathological states of mind.

Robert Gober, Untitled (1989).

Gober’s angry metaphorical sculpture consists of two bags of cat litter and an empty wedding dress standing in a room decorated with wallpaper. Its repeated motifs are a sleeping white man and a lynched black man. The litter signifies America’s attempt to deodorize a history founded on racism and the fallacy of white heterosexual purity.

Carl Olof Larsson, The Bridge (1912).

The focal point of the Swedish artist’s mysterious watercolor is the supple little cat, which peers, as does its mistress, at the male figure on the bridge. An invisible thread connects the cat’s black coat to the dark head of the man; one expects the cat to tug it, drawing the man’s attention to the woman who had, perhaps, sat down to paint the bridge in solitude.

Georg Baselitz, Cat Head (1966–67).

Baselitz’s brutish humanoid cat dominates a smaller dog, from which it is separated by a fence. This typical inversion by the figurative expressionist-cum-postmodernist painter is both a commentary on ruined post-Nazi Germany and conflicting artistic movements within the divided country.

Kees von Dongen, Woman With Cat (1908).

This painting by the Dutch Fauvist is distinguished by its juxtaposing of delicate colors, its serenity, and its wit. The position in which the woman tenderly holds the cat renders her almost androgynous. The bow-like curve of the cat’s tail, its long body, and the woman’s headpiece harmonizes all the elements.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Girl and Cat (1880–81).

Most of Renoir’s paintings featuring females and felines are supine, like those of Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. This one is the most vital. Something in the flowers has made the cat rear, mildly alerting the girl to its erect posture. The balance between indifference and inquisitiveness is perfectly weighted.