Spare a thought for the art historians of the future: They’ll be stuck combing through messenger threads and decoding emojis for insight into their objects of study, instead of reading letters. If you need to be reminded of what a loss that is, take a peek at Artists’ Letters: Leonardo da Vinci to David Hockney, a new book brings together 100 pieces of correspondence from some of the most famous artists of the last 600 years.

The assembled missives are entertaining in their glimpses of the everyday thoughts of artists, and sometimes downright moving. The letters range from the poignantly prosaic (“I beg you, kind Sir, to have my payment order prepared promptly, so that I will now finally receive my well-earned 1244 guilders,” a destitute Rembrandt begs a patron) to the overpoweringly intimate (“Let your dear hands rest on my face, so that my flesh can be happy that my heart feels once again suffused with your divine love,” writes Rodin to Camille Claudel, around 1886).

“Artists’ Letters: Leonardo da Vinci to David Hockney,” 2019. Courtesy of White Lion Publishing.

The book, set to come out October 1 from White Lion Publishing, was edited by Michael Bird. The British writer and lecturer has been behind a number of art historical texts targeted at a popular readership, most notably “100 Ideas that Changed Art,” from 2012.

Bird combed through thousands of documents in the process of putting together his newest project, a curated compilation of letters that charts the evolution of the art world from the 1500s to today. It includes names such as Francisco Goya, Pablo Picasso, Joseph Cornel, Frida Kahlo, and Yayoi Kusama.

Sorted into sections like “Artist to Artist,” “Love,” and “Professional Matters,” the letters range in tone from biting to banal, sublime to silly—much like the work of the artists that inspired them. In some cases, the texts humanize the figure who is writing; others add to the artistic legend.

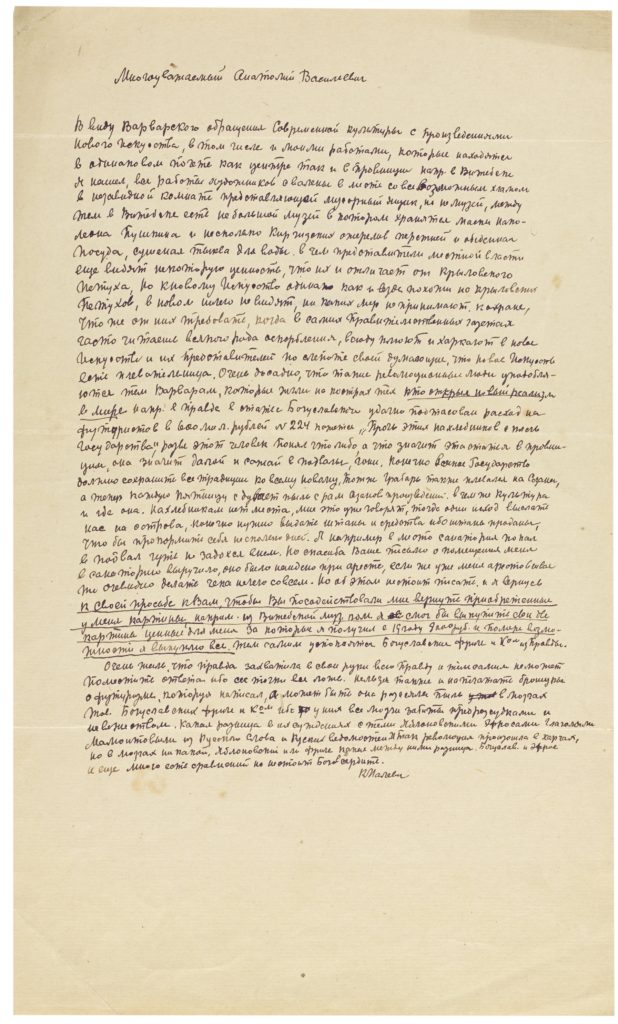

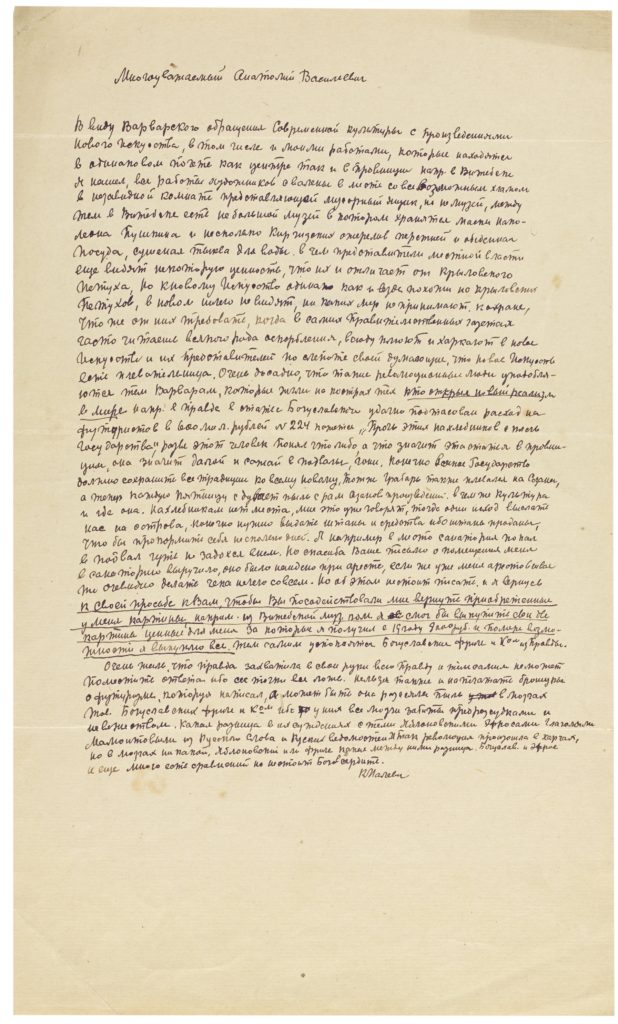

A letter from Kazimir Malevich to Anatoly Lunacharsky, November 1921.

There’s a strange pleasure, too, in seeing the actual handwriting of the famous artists as well as doodles and notes in the marginalia. Van Gogh’s handwriting is surprising graceful and measured; Marcel Duchamp is virtually unreadable.

A 1945 birthday invite from George Grosz illustrates in cartoon fashion how much Hennessy he plans to drink on his special day. (He may have started early, given the nonsensical text: “You are cordially invited to attend the birthday Party of ME Thursday 26 afternoon / we will have lots of drinks, this time ME too.”) A particularly memorable 1973 note from Judy Chicago to Lucy Lippard (more on that below) has stickers of butterflies and cats, a drawing of a rainbow, and a note that reads, “This is definitely not a ‘cool’ letter…”

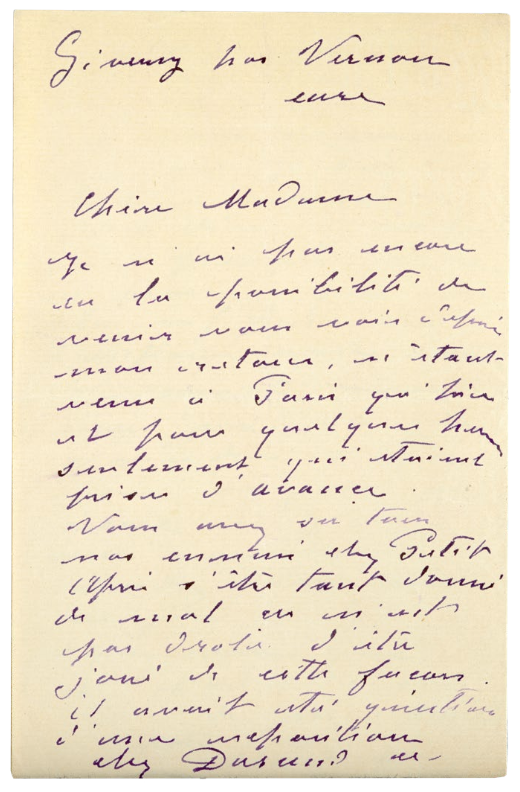

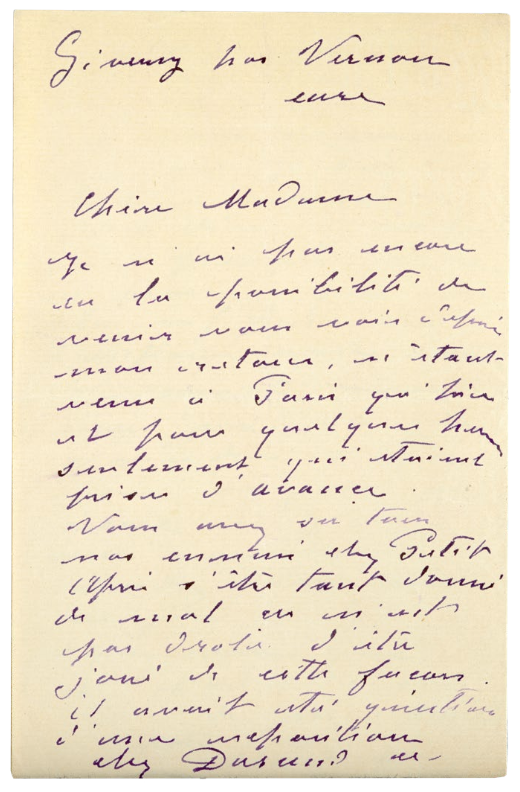

A May 1888 letter from Claude Monet to Berthe Morisot. Courtesy of White Lion Publishing. excerpts from them below:

Below, here are five of our favorite passages from Artists’ Letters:

Michelangelo, in a tightly written 1550 dispatch to his nephew, offers some blunt, mercenary advice about marriage:

About your taking a wife—which is necessary—I’ve nothing to say to you, except that you should not be particular as to the dowry, because possessions are of less value than people. All you need have an eye to is birth, good health and, above all, a nice disposition. As regards beauty, not being, after all, the most handsome youth in Florence yourself, you need not bother overmuch, provided she is neither deformed nor ill-favoured. I think that’s all on this point.

William Blake, in 1804, is glimpsed extravagantly trying to win the good graces of a client after a blown deadline delivering some illustrations he had been commissioned to produce for a biography of William Cowper:

Engraving is Eternal work; the two plates are almost finish’d. You will receive proofs of them for Lady Hesketh, whose copy of Cowper’s letters ought to be printed in letters of Gold & ornamented with Jewels of Heaven, Havilah, Eden & all the countries where Jewels abound. I curse & bless Engraving alternately, because it takes so much time & is so untractable, tho’ capable of such beauty & perfection.

A pre-fame Andy Warhol offered a flash of vulnerability in this incredibly abbreviated, self-effacing auto-biography he sent to Harper’s editor Russell Lynes, in 1949:

biographical information

my life couldn’t fill a penny post card

i was born in pittsburgh in 1928 (like everybody else—in a steel mill)

i graduated from Carnegie tech now i’m in NY city moving from one roach infested apartment to another.

Robert Smithson waxes prophetically anti-capitalist to a European colleague in a letter about the importance of his Netherlands-based earthwork Broken Circle/Spiral Hill, in 1971:

As Jennifer Licht says, ‘art is less and less about objects you can place in a museum’. Yet, the ruling classes are still intent on turning their Picassos into capital. Museums of Modern Art are more and more like banks for the super-rich. […] Art should be an ongoing development that reaches all classes.

And, in the thick of the feminist art movement, Judy Chicago explains the connections between her artistic and creative evolution to Lucy Lippard (who, based on this collection, seems to have gotten a lot of great letters), in the summer of 1973:

You know, a lot of people have hassled me in the last several years about whether my ‘political activity’ was interfering with my art, and it always made me feel vaguely guilty […] I suddenly realized that the guilt was similar to the guilt I used to feel when people implied that I was somehow stepping out of ‘female role’ … there is really an ‘artist role’ and I am determined to break out of it […] That role demands that the artist, like the woman, be victim … dependent upon the approval of the Establishment […] Anyway, you know … in this time of great change […] artmaking and art become essential. If the relationship of the artist to her community changes, then people can ‘be involved’ in art in a way they are not now, and the artist can cease to be victim, the barriers between art forms will break down, the barriers between art ‘roles’ will end.