People

In Case You Missed ‘Shoot,’ an Actor Is Now Re-Staging Chris Burden’s Most Shocking Performances in New York

The play looks at the artist's conflicted relationships and the preparations that went into his performances.

The play looks at the artist's conflicted relationships and the preparations that went into his performances.

Janelle Zara

“I was essentially waterboarding myself.”

That’s how actor Ben Hethcoat describes his reenactment of Chris Burden’s 1974 performance Velvet Water. In the opening scene of “A Beast/A Burden,” a play coming to the SoHo Playhouse in New York on January 3, Hethcoat (as Burden) walks on stage and submerges his head in a bucket of water, emerging intermittently, choking and sputtering to the consternation of the audience.

He repeats the phrase Burden used to introduce the original performance: “Today, I am going to breathe water, which is the opposite of drowning, because when you breathe water you believe water to be a richer, thicker oxygen capable of sustaining life.”

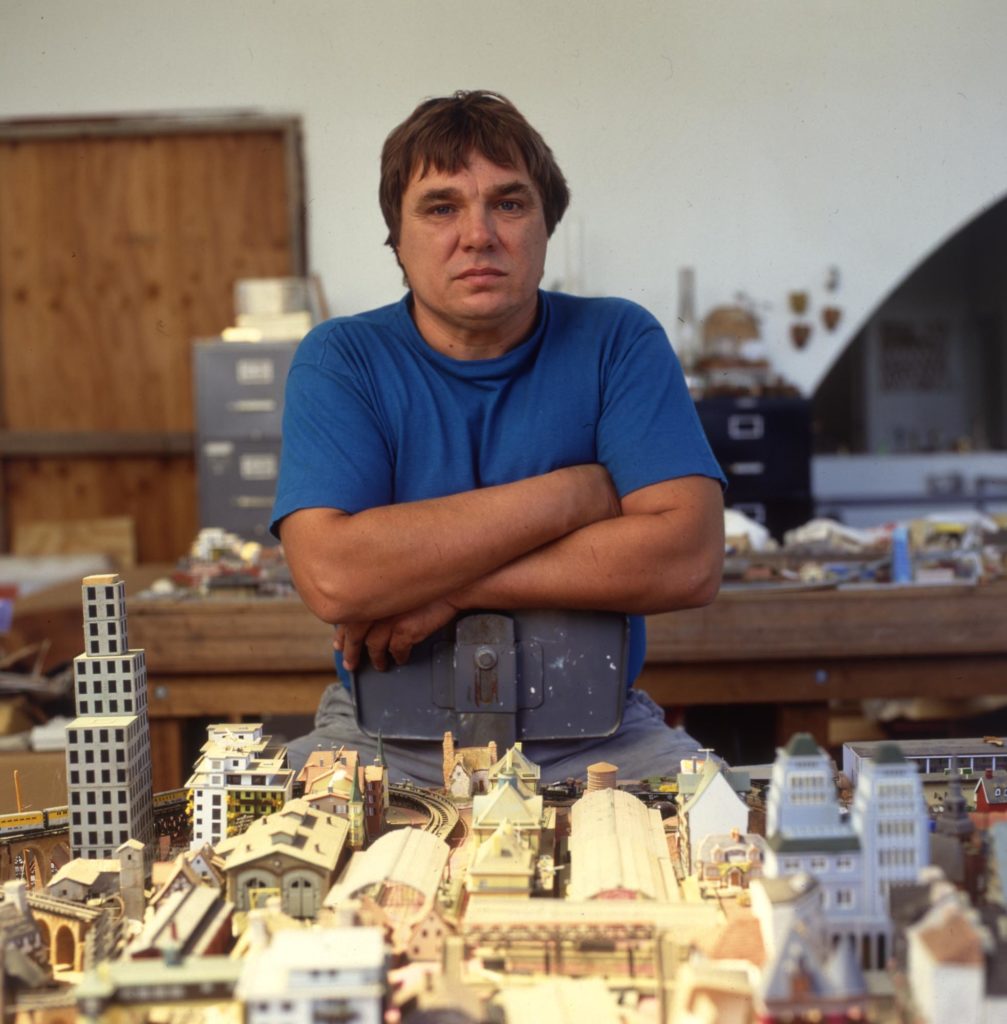

Ben Hethcoat in scene from “A Beast/A Burden,” written by Billy Ray Brewton. Screenshot courtesy of Vimeo.

“It automatically sets up this protagonist as an unreliable narrator,” Hethcoat says. “Clearly I’m not breathing water, and neither was Burden.”

“A Beast/A Burden,” which debuted at the Hollywood Fringe Festival last summer, focuses on a handful of Burden’s most provocative performances from the early 1970s, including Prelude to 220, or 110 (1971), in which the artist lay bolted to a concrete floor near two electrified buckets of water. The tension of the work lay in the improbable possibility that a viewer would kick over a bucket, thereby electrocuting the artist.

“I leaned toward the pieces where Burden put himself in the most personal harm, whether it was physical harm or in terms of his relationships,” says playwright and director Billy Ray Brewton. “But they’re all only the illusion of harm.”

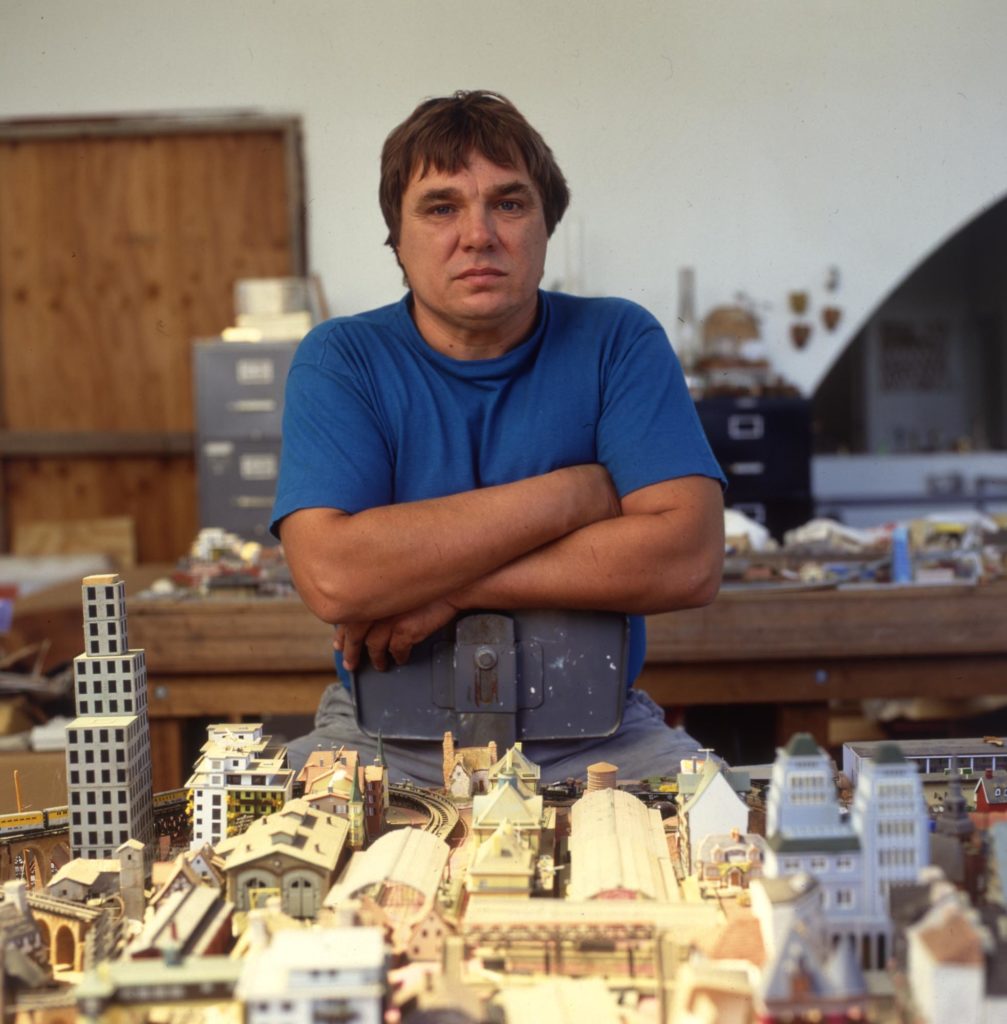

A still from the documentary Burden (2016), showing the artist performing Trans-Fixed (1972). Courtesy Magnolia Pictures.

During his research, Brewton found that Burden’s performances were actually methodically controlled. (The exception is the 1971 performance Shoot, in which a marksman aiming to graze Burden with a bullet actually shot him in the arm. That performance is also featured in the play.)

Brewton also found his feelings for Burden increasingly conflicted, particularly in light of the artist’s relationships with women. One scene in the play imagines a dialogue between Burden and his first wife, Barbara, elucidating the turmoil in their relationship. It goes on to depict Confession, the real-life 1974 video work in which Burden publicly professed an extramarital affair.

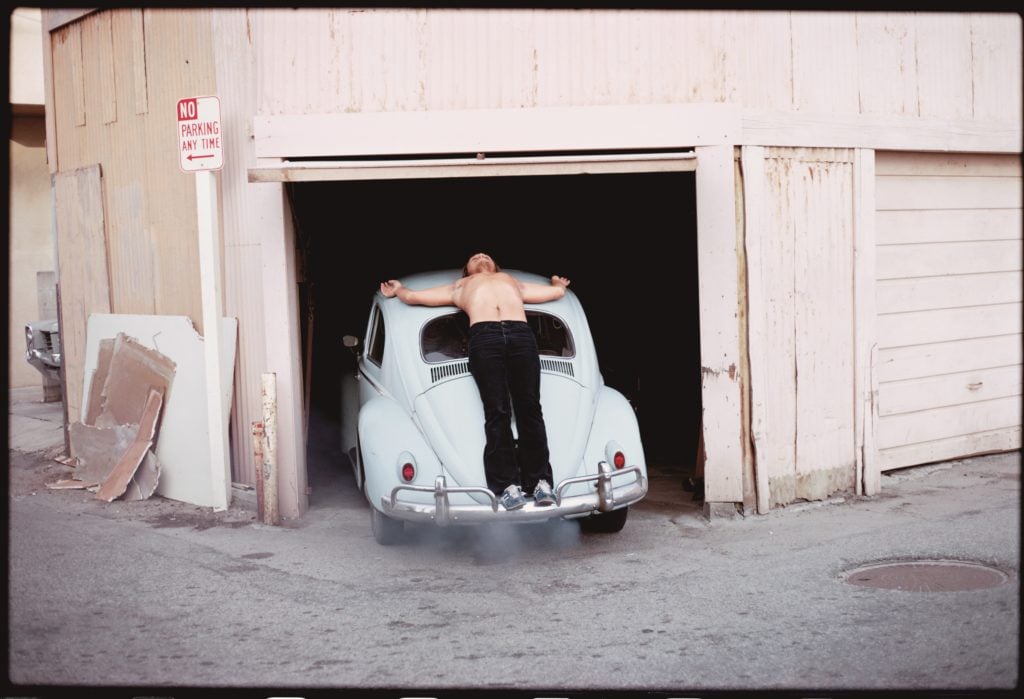

Chris Burden’s Piracy, vol. 1 (1973–77) on the left. On the right, a scene from “A Beast/A Burden.”

To get into character, Hethcoat used an outside-in approach, starting with Burden’s appearance, before moving on to his physicality and mannerisms. He gained weight and adopted the mustache and ad hoc hairstyle Burden wore in the 1970s. Before each production, Hethcoat also recites the phrase “seventeen-thousand, two-hundred ten,” paying close attention to how Burden, who had a residual accent from his Massachusetts upbringing, would enunciate the phrase.

For Hethcoat, the essential difference between a performance artist and an actor is that artist assumes a mission, not a character. The distinction begins to blur in a “A Beast/A Burden,” as the discomfort that Burden’s viewers endured is now transferred to a playhouse audience.

A scene from Matthew Marcum’s “Pollock: A Frequency Parable.” Courtesy of Matthew Marcum.

At the SoHo Playhouse, the play will be performed as one half of “Nature and Purpose.” The second half, “Pollock: A Frequency Parable,” is a separate play created by and staring Matthew Marcum. The 30-minute performance translates the essence of Jackson Pollock’s paintings into a vocally-driven work. In this case, we can promise that no one gets hurt.