Art World

17 Disruptors Who Have Completely Changed the Art World

Who is responsible for the art world as we know it today?

Photo courtesy Artlist.

Who is responsible for the art world as we know it today?

Brian Boucher

Who has created the art world as we know it in recent years? And who may be doing so now?

The concept of “disruption” got its start in Clayton Christensen’s 2011 book The Innovator’s Dilemma: The Revolutionary Book that will Change the Way You Do Business.

It’s also been reduced to a buzzword. In the past few years, it seems like every startup hopes to disrupt something or other. The word has even been used to promote a good old-fashioned wooden cuckoo clock, said a New York magazine writer in a desperate appeal to stop using the word altogether.

Still, we think it’s a useful concept for thinking through who has helped to create the art world we live in today. We at artnet News put our heads together, polled some art-world veterans for suggestions, and assembled this admittedly subjective, non-comprehensive list of colleagues who have changed the shape of the American art world.

Anne Pasternak.

Photo Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, courtesy Creative Time.

1. Anne Pasternak, Promoting Public Art

Over two decades as director at Creative Time—half the lifespan of the New York public art organization—Anne Pasternak oversaw dramatic projects like Kara Walker’s blockbuster A Subtlety at the Domino Sugar Factory while expanding the organization’s budget and staff by orders of magnitude, helping to bring public art to greater visibility (along with colleagues like Nicholas Baume, of Public Art Fund). Creative Time even snagged a spot on the artist list for Okwui Enwezor’s Venice Biennale.

With chief curator Nato Thompson, she’s highlighted socially engaged projects, often given a platform at the annual Creative Time Summit, and she’s set editor Marisa Mazria Katz loose with Creative Time Reports, a web publication in which artists comment on the issues of the day.

She’s now headed to the helm of the second-largest museum in New York, the Brooklyn Museum. She takes over September 1, and the art world is eager to see how she’ll shake things up.

RoseLee Goldberg.

Photo: Will Ragozzino, courtesy Patrick McMullan/Performa.

2. and 3. The Performers: RoseLee Goldberg and Jay Sanders

Two curators have raised the profile of performance immeasurably in the last several years: RoseLee Goldberg, art historian and founder of the Performa biennial, and Jay Sanders, curator of performance at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. In an era when the market tends to dominate the conversation, many have welcomed a focus on less-commodifiable works of art.

Since the first Performa, in 2005, the New York biennial devoted to performance has seen acclaimed works by artists like Joan Jonas, Ragnar Kjartansson, Liz Magic Laser, Adam Pendleton, and Alexandre Singh, and choreographers Jérôme Bel and Yvonne Rainer; the biennial has also directed renewed attention to historical practitioners like choreographer Martha Graham and artist Allan Kaprow.

Jay Sanders.

Photo courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art.

With Elisabeth Sussman, Sanders co-curated the 2012 Whitney Biennial, during which, for the first time, the entire fourth floor of the museum’s Upper East Side building was devoted to performance, music, theater, and other events. For her challenging performance, British choreographer Sarah Michelson took home the $100,000 Bucksbaum Award, presented to one artist in each Biennial—the first time that the winner fell outside of the traditional confines of visual art.

And for better or worse, Joe Scanlan’s 2014 biennial performance centered on a fictitious black artist, Donelle Woolford (included at the invitation of Michelle Grabner), gave rise to some of the liveliest debates about race and gender in the art world in years, placing performance art at the center of the conversation.

Cady Noland at Documenta IX in 2006.

Photo: Klaus Baum.

4. Cady Noland: Artist, Dropout, Denier

In an art market that sees artists’ careers harmed when their prices get out of control when rapidly sold and resold at auction, Cady Noland’s tight grip on her existing works can be seen as a serious act of defiance. She would rather you not see her work at all than that you should see it in the wrong context or if it’s not up to her standards.

She disowned the work Cowboys Milking in 2011 on the eve of its auction at Sotheby’s New York, tagged with an estimate of up to $350,000. Invoking the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990, she declared that minor damage completely invalidated the work, and that her reputation would be harmed by its sale. She also disrupted another sale recently, when she realized the work had been restored.

Upending what you might think of as the authority of art patrons over their artists, she has forced even the most powerful collectors, such as Peter Brant, to post disclaimers when showing or selling her work, like this gem shown by dealer Christopher D’Amelio at Art Basel in 2012: ““Ms. Noland does not consider Christopher D’Amelio to be an expert or authority on her artwork.”

New York Representative Jerrold Nadler.

5. Jerrold Nadler, Lobbying for Artists

New York Democratic representative Jerrold Nadler aims to change the way auction houses operate, to make their jaw-dropping sales benefit not only sellers and houses, by also artists. The congressman has been working for years to get artists a cut of the consignor’s profit. And he pulls no punches when it comes to Christie’s and Sotheby’s, claiming that the auction houses negotiated with him in poor faith, getting concessions from him and then opposing the bill anyway.

Nadler has reintroduced the legislation, which he says is well positioned to pass this time around.

ArtList founders Maxime Germain, Kenneth Schlenker, and Astrid de Maismont.

Photo: Benjamin Norman/New York Times

6. ArtList, Talking Trash to Power

But you know who really hates auction houses? It’s the online art reseller Artlist, who launched earlier this year and printed a T shirt reading “Fuck Christie’s and Sotheby’s.” The online seller promises to funnel half the commission from each sale to the artist whose work goes on the auction block, like Nader wants the bigger houses to do. And it’s not just low-priced art on offer.

One of their first big sales, listed at $400,000, was for a Danh Vo work; a set of Andy Warhol Mao screen prints now on offer is tagged at nearly $1.4 million. Plenty of artworks at the major houses go for less than that.

Joseph Grima and Sarah Herda.

Grima photo Seth Lowe, Herda photo Victor Jeffries, courtesy Chicago Architectural Biennial.

7. and 8. Joseph Grima and Sarah Herda, Founders, Chicago Architecture Biennial

How is it exactly that there has been no major recurring architecture exhibition except the Venice Architecture Biennale, even in the U.S.? Let that sink in for a moment.

Enter Joseph Grima and Sarah Herda, the founders of the Chicago Architecture Biennial and the artistic directors of “The State of the Art of Architecture,” its inaugural 2015 outing (October 3, 2015–January 3, 2016). The Windy City has been a hotbed for architectural practice, with giants like Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Mies van der Rohe having major projects there.

At a recent press presentation, a slide show presenting the participants made it clear that the roster is diverse. Activist leanings are visible in names like André Jaque’s Office for Political Innovation; and it’s not just about creating buildings, as shown with the inclusion of the Heritage Foundation Pakistan (founded by architect Yasmeen Lari, who claims to be her country’s first female architect), which documents and conserves that country’s historic built environment.

Participants come from cities as far-flung as Ho Chi Minh City, Rio de Janeiro, and Lagos.

Ambre Kelly and Andrew Gori.

Photo Samuel Sachs Morgan, courtesy Spring Break Art Show.

9. and 10. Ambre Kelly and Andrew Gori, Spring Breakers

You’ve heard every critique of fairs, but Spring Break Art Show breaks the mold; the fair “succeeds in setting itself apart,” even for the tough critics at Art F City. The invited participants are typically curators, not dealers, and they select artworks based on a theme, like transaction (2015) or the public versus the private (2014).

What’s more, the booths cost the exhibitors nothing up front; the organizers take a percentage of exhibitors’ sales, so the presentations can afford to be more experimental and less of a commercial slam dunk. (Big fairs like Armory, to which Spring Break is timed, charge up to $70,000 for a booth.) To make it all possible, Kelly and Gori seek out spaces they can use for nothing, like the run-down Daniel Moynihan Station, which provided an ironically decrepit backdrop for the 2015 edition.

Andrew Edlin and Valérie Rousseau.

Photo: Patrick McMullan.

11. and 12. Andrew Edlin and Valérie Rousseau, Outsider Art Power Couple

Philadelphia Outsider Art dealer John Ollmann recalls that “Back in 1970, when we first started showing this material seriously, we couldn’t buy attention, good or bad. It was simply ignored. Now ‘suddenly’ people are discovering Bill Traylor, James Castle William Edmondson, Henry Darger, and Martin Ramirez.”

New York dealer Andrew Edlin didn’t create the wave of interest in Outsider Art, which has even seen many untrained practitioners showcased in “The Encyclopedic Palace,” the main exhibition at the 2013 Venice Biennale, but he’s proven adept at riding it. It started with a family connection: Edlin’s uncle Paul was an untrained artist, and he was his nephew’s first client.

Now Edlin runs a storefront gallery in Chelsea (soon moving to the Lower East Side) and owns the Outsider Art Fair, which he bought in 2012 and then expanded to Paris in 2013. Dealers credit him with markedly professionalizing the fair.

His wife, meanwhile, is Valérie Rousseau, who is organizing attention-getting shows like a Bill Traylor exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum (AFAM), where she was hired as curator of 20th-century and contemporary art in 2013. If ever a museum needed new life, it’s the AFAM, which lost its Tod Williams and Billie Tsien–designed home on West 53rd Street in 2011 and then saw it razed by the Museum of Modern Art, which bought it. It is evident that there is new energy at the museum, where the board has rallied.

Theaster Gates

Photo: Sara Pooley via Architectural Record

13. and 14. Theaster Gates and Rick Lowe, Social Sculptors

Ever since Joseph Beuys coined the term “social sculpture,” artists have been thinking through the German artist’s concept. Two practitioners who have made moving use of this mode of art-making are Chicago’s Theaster Gates and Houston’s Rick Lowe. They’ve both worked to use culture to redevelop neighborhoods plentiful with abandoned buildings—and make sure there’s a payoff for the people who have lived there, and not just gentrifiers.

“Very significant people in the city and beyond would find themselves in the middle of the hood” when they visit his Dorchester Projects, named for the street where the project started, says Gates in a TED Talk that has garnered nearly three-quarters of a million views. He has bought up nearly 70 abandoned properties, including a crack house he transformed into Black Cinema House, a movie theater that took off so well that it had to move to a larger facility. He’s now at work rehabbing a massive neoclassical bank building near Hyde Park.

And when he won the Artes Mundi award in January 2015, he disrupted that too: he split the £40,000 cash prize, the largest for the arts in the UK, with his fellow nominees.

Rick Lowe

Photo: Brett Coomer, courtesy the Houston Chronicle.

Gates was just 20 and over a decade away from his breakout Chicago performance when artist Rick Lowe launched Project Row Houses in 1993, buying up nearly two dozen 1930s-era shotgun houses that were headed for demolition. They have played host to programs like transitional housing for single mothers and various education initiatives, and the pioneering venture, foundational to the “social practice” genre, won him the $625,000 MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant. Lowe says that he aims to empower people to “exercise their power as creative practitioners,” in keeping with Beuys’ proposition that “every human being is an artist.”

15. and 16. The USC7 and Cooper Union Students and Graduates

Art education in the U.S. is in danger from the galloping commercialization that threatens the entire cultural field, and two groups of art students and graduates, on both coasts, have stood up to school administrations.

The USC7, as they have come to be known, were once the class of 2016 at the renowned Roski School of Art at the University of Southern California. That was before it became the more commercially oriented Roski School of Art and Design, and before the school reneged on financial promises, gutted parts of the program, and offloaded valued faculty members. So the students dropped out en masse, seriously impacting the school’s recruitment efforts—an indication that the balance of power between school administration and students is not as one-sided as you might think.

And on the East Coast, students and alumni of the financially beleaguered college The Cooper Union (with schools of art, architecture, and engineering) have challenged a fundamental policy change. Formerly tuition-free for all, the school began to charge students after revealing that the beloved institution’s books were consistently in the red over decades—despite its own sunny declarations to the press just a few years ago.

Students and graduates cried foul, occupying the president’s office, declaring that founder Peter Cooper’s mission of maintaining a school “as free as air and water” must remain paramount, and filing a lawsuit alleging mismanagement. Soon enough, the Attorney General had begun an investigation, resulting in the abrupt departure of five trustees who were in favor of tuition. So, again, who says that a bunch of paint-stained 20-year-olds can’t turn the tables on the suits?

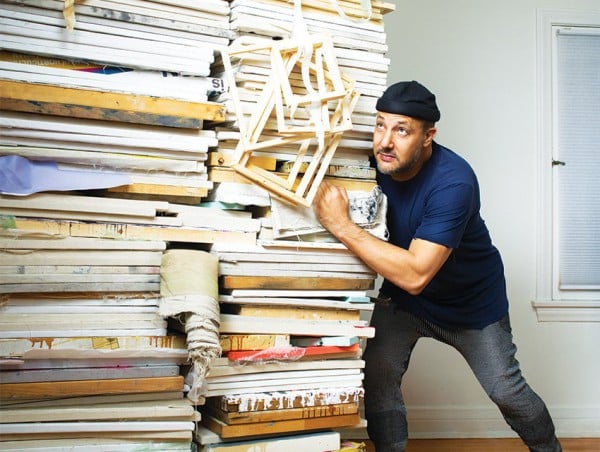

Stephen Simchowitz with Untitled Stack by Zachary Armstrong

Photo: Gregg Segal via LA Mag

17. Stefan Simchowitz

You didn’t think you were going to get through a list of disruptors without reading about Stefan Simchowitz, the self-declared disruptor extraordinaire, did you? Talking to the New York Observer about the $200-million sale to Getty Images of his business, MediaVast, the Los Angeles-based collector/dealer said, “The disruption becomes the new establishment, and the establishment is once again attacked, then is hopefully attacked again to become the new establishment.” So is he a disruptor or, now that he’s selling art online, part of the establishment?

He’s plowed the money from the sale of his company into collecting artists who have gone on to become hot—Joe Bradley, Ryan McGinley, Oscar Murillo, Sterling Ruby—sometimes supporting the artists financially in return for all the work they produce. He harnesses his avid social media following to create what he terms “virality” around the artists he likes, and argues that art flipping is good because it generates headlines that gin up more interest in art.

Patrons have supported artists in return for their production before, to be fair, and Instagramming doesn’t necessarily equate to “breaking shit,” the buzzy phrase that’s trying to dethrone “disrupt.” So is he or isn’t he a disruptor? What do you think?

Related stories:

Top 200 Art Collectors 2015 Part One

Top 200 Art Collectors 2015 Part Two

62 Women Share Their Secrets to Art World Success: Part One