Law & Politics

Long Hidden From the Public Eye, These Artistic Treasures From 1924 Are Now Entering the Public Domain

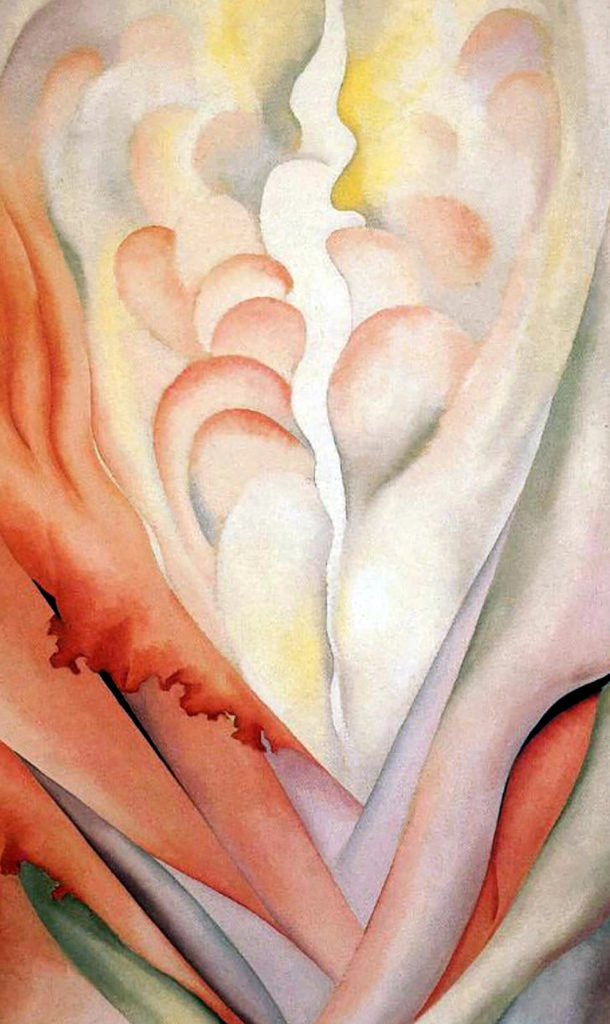

Works by Georgia O'Keeffe, Lyonel Feininger, and other US artists are now free to be reproduced.

Works by Georgia O'Keeffe, Lyonel Feininger, and other US artists are now free to be reproduced.

Sarah Cascone

January 1 marked not only the start of 2020, but also Public Domain Day, when the copyright on a trove of long-protected works of art created in 1924 finally expired. Now, a cache of 95-year-old paintings, sculptures, films, and works of literature can be freely reproduced for the first time.

The new set of public domain goodies include the first film adaptation of Peter Pan, EM Forster’s A Passage to India, and George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, to name just a few.

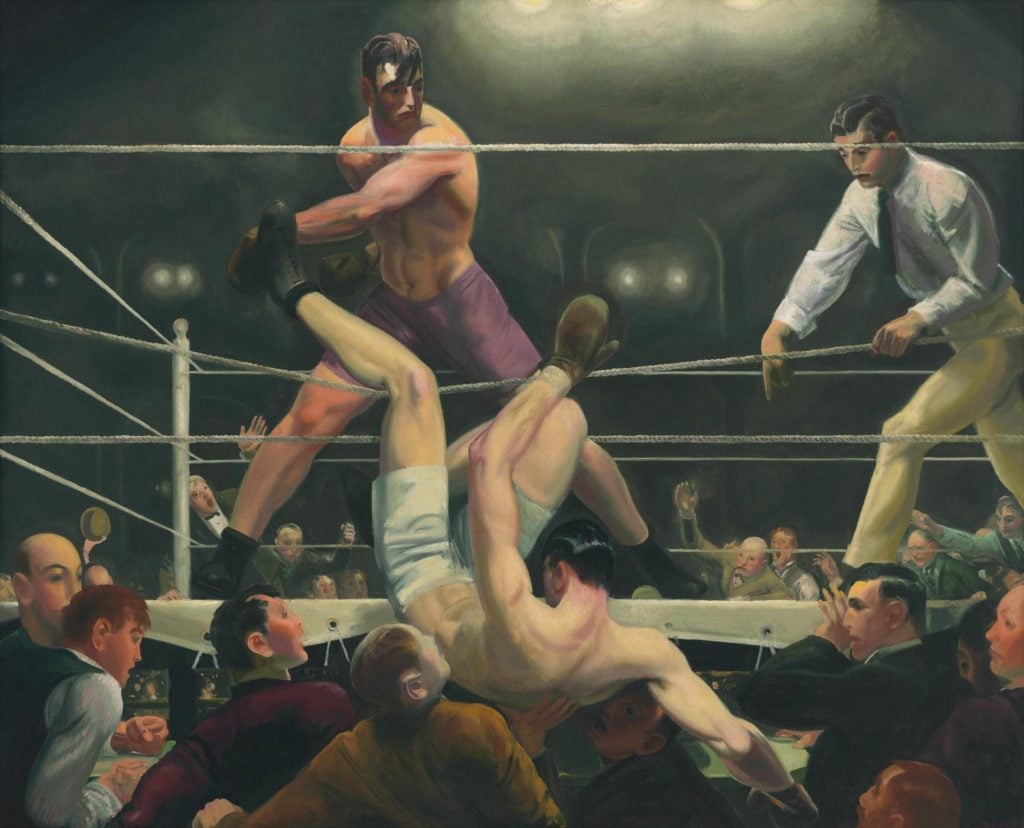

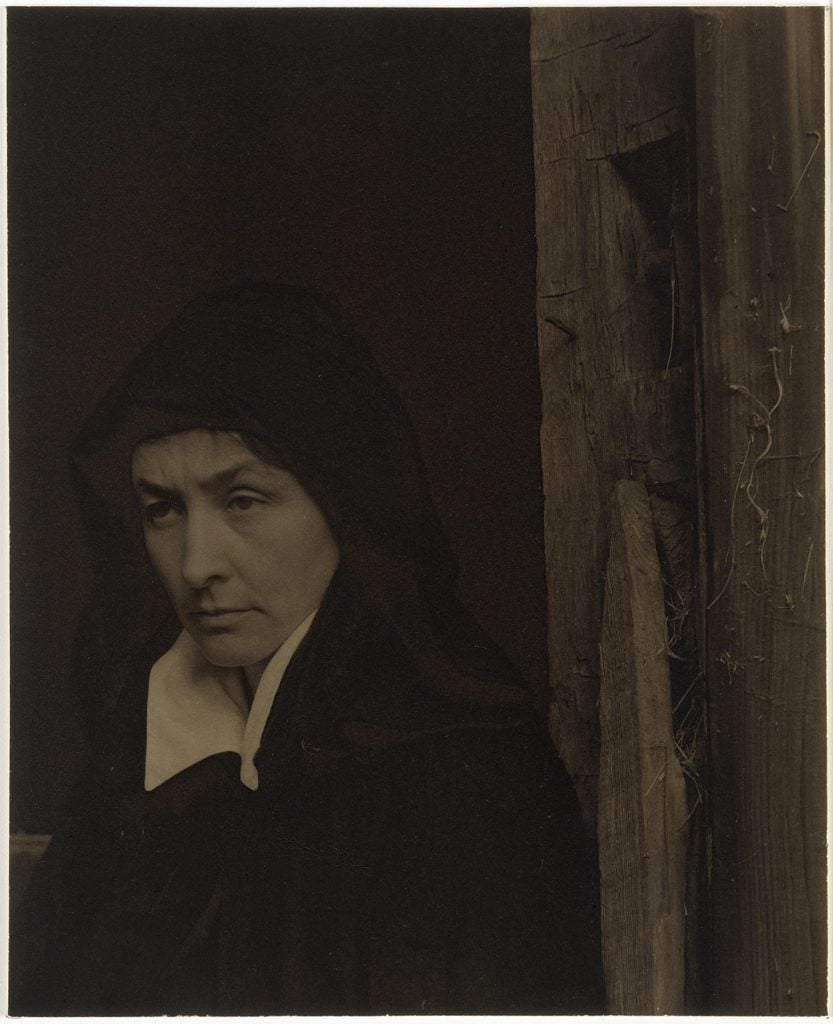

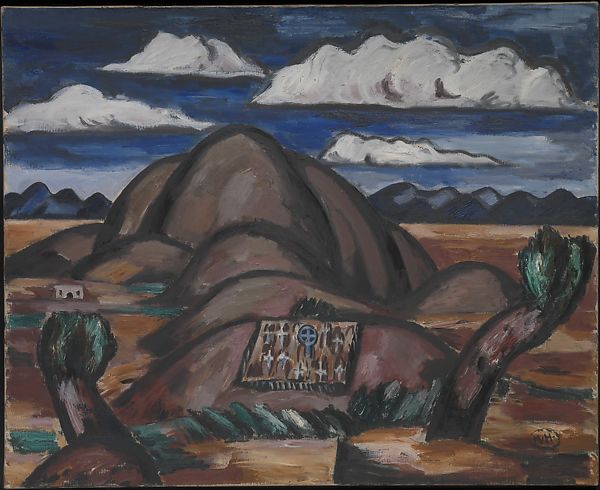

In the visual arts, there’s now free rein to reproduce Georgia O’Keeffe’s Flower Abstraction, George Bellows’s Dempsey and Firpo, and Pamela Bianco’s Madonna and Child, all from the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Meanwhile, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s catalogue includes such 1924 works as Alfred Stieglitz’s striking portrait of O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley’s Cemetery, New Mexico, and a number of elegant line drawings of women by Gaston Lachaise.

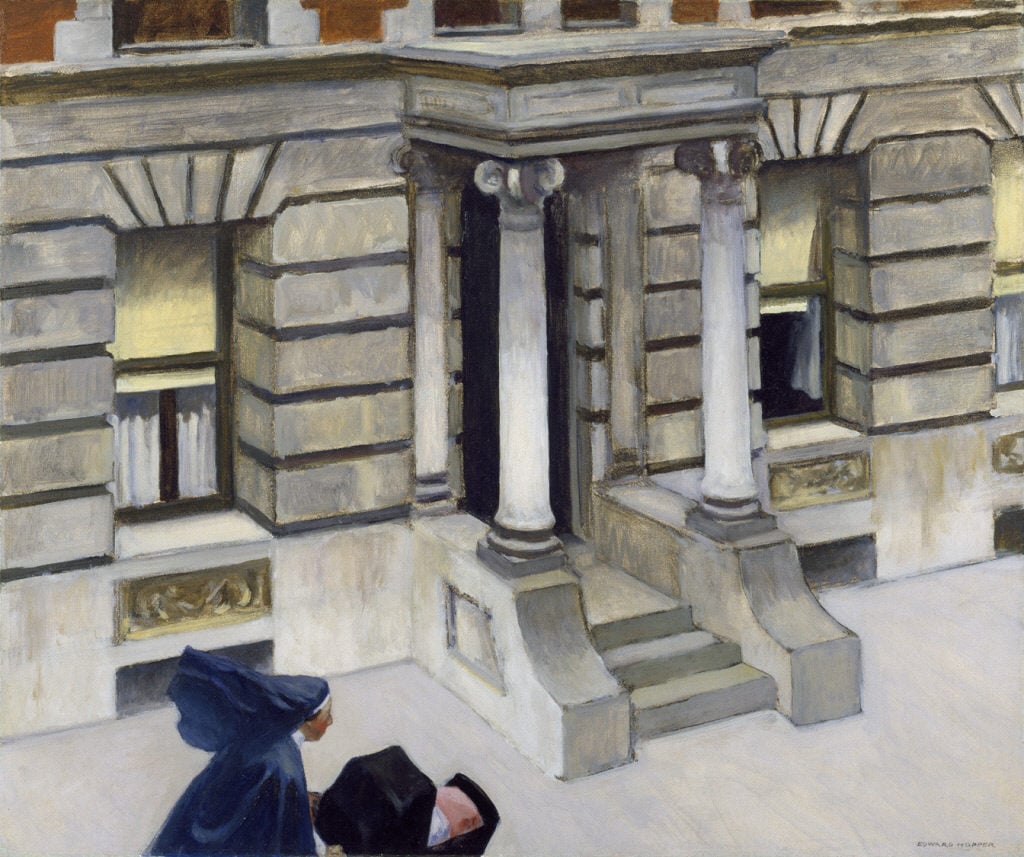

Among the other notable works now entering the public domain are Edward Hopper’s New York Pavements at Virginia’s Chrysler Museum, Romaine Brooks’s Una, Lady Troubridge at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and Lyonel Feininger’s Gaberndorf II at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

The first film adaptation of J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan (1924).

Public Domain Day used to be an annual event, until the Sonny Bono Copyright Extension Act of 1998, which extended copyright to a period of 95 years. That effectively froze intellectual property in time for the next two decades, preventing works from becoming free to all until January 1, 2019. (US Copyright law previously got beefed up in 1978—before that, creators only enjoyed a 56-year copyright term, which would have seen the Maurice Sendak’s 1963 classic Where the Wild Things Are, among other works, enter public domain this year.)

The Gershwin Family Trust and Disney were among the most vocal supporters of extending copyright, looking to retain royalties and creative control over properties like Mickey Mouse (the character’s debut on-screen appearance, in the short 1928 film Steamboat Willie, is protected until 2024).

But the law also restricts access to work that has long ceased to be commercially viable, and limits artists, musicians, authors, and others from taking inspiration from great works from the past—think of the way West Side Story was drawn from William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Such practices may be fuzzier in the visual arts, where appropriation art is a genre unto itself, but the 95-year copyright period still stifles new artistic experimentation, as well as preventing the public from enjoying past works.

The Met’s website does not show even thumbnail images of many artworks from 1924, but those works passed into public domain on the first of the year. Screenshot of the Metropolitan Museum of Art website.

“The vast majority of works from 1924 are out of circulation,” wrote Balfour Smith of the Center for the Study of Public Domain at Duke Law School in an article celebrating this year’s Public Domain Day. “After 95 years, many of these works are already lost or literally disintegrating (as with old films and recordings), evidence of what long copyright terms do to the conservation of cultural artifacts.”

Projects like 1923, a monthly zine created by Parker Higgins that last year republished various lost treasures that had finally entered public domain, show how many works under copyright have been forgotten.

“The public domain also enables access to cultural materials that might otherwise be lost to history,” wrote Smith. “Thanks to public domain, anyone can make them available online, where we can discover, enjoy, and breathe new life into them.”

See more works newly admitted to the public domain below.

George Bellows, Dempsey and Firpo (1924). Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Lyonel Feininger, Gaberndorf II (1924). Courtesy of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City.

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe (1924). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Edward Hopper, New York Pavements (1924). Courtesy of the Chrysler Museum of Art.

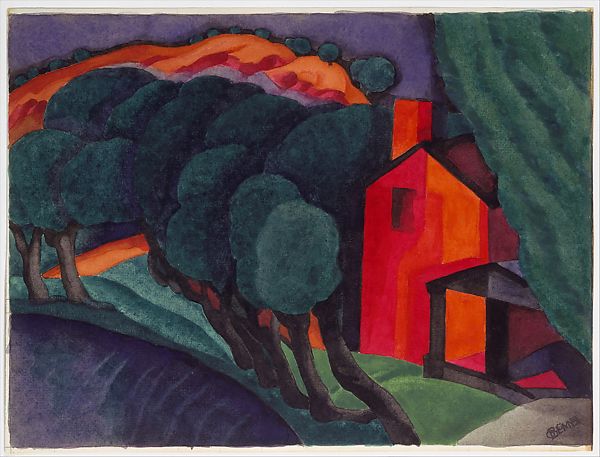

Oscar Bluemner, Glowing Night (1924). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Marsden Hartley, Cemetery, New Mexico (1924). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.