Art World

Here Are 8 of the Best Works We Saw Around the World in 2023

From New York to Istanbul, we saw a lot of art this year. Here are our favorites.

From New York to Istanbul, we saw a lot of art this year. Here are our favorites.

Artnet News

As another tumultuous year draws to a close, the team at Artnet News took the opportunity to look back at all the art we’ve seen since January.

As always, the busy art world calendar is filled with a seemingly endless array of gallery shows, museum exhibitions, biennials, and art fairs. But scrolling back through the countless photos and videos of paintings, sculptures, performances, and other pieces that we’ve taken over the past year, certain works stuck out in our memories, be it for their craftsmanship, their meaning, or sheer artistic virtuosity.

Here are our writers and editors’ picks for the best works of the year.

Delcy Morelos, El abrazo (The Embrace), 2023, at Dia Chelsea, New York (detail). Photo by Don Stahl, ©Delcy Morelos.

My number one art show of the year, and it’s not even close. Immediately impressive but rewarding of your time, and filling one huge room at Dia Chelsea, this immense, levitating geometric mass of earth and grass is an artwork from 2023 that I will not forget.

It’s not just about the scale, although it is thrilling to see an artist this thoughtful work on a large scale. In its confidence and calm of its elemental symbolism, El abrazo—and its companion piece, Cielo terrenal—manages to make you feel as if you are in the presence of a fresh piece of sacred architecture.

—Ben Davis

Beatriz Cortez, Ilopango, the Volcano that Left (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council. Photo: Michael Valiquette.

My favorite art experience of the year was “Shifting Center,” which took over the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York this fall. But because answering this question with a whole exhibition feels like cheating, I’ll go with the work of art that best exemplified the ear-and eye-opening ways the show explored psychoacoustics to talk about dislocation: Beatriz Cortez’s Ilopango, the Volcano that Left (2023).

The sculpture, a mountainous hunk of steel the artist shaped by banging it like a drum, was sailed up the Hudson River from the Storm King Art Center to Troy, then installed smack-dab in the middle of EMPAC’s central concert hall. The way it hijacks the music space, spatially and sonically, feels like colonialization. But Cortez—who was inspired by the 6th-century volcano that erupted in what is now El Salvador, her home country—has a more poetic, diasporic framework in mind.

“I became fascinated by the idea that the particles of earth from the underworld were spread all over the planet,” she said. “Indigenous peoples, even contemporary Indigenous peoples migrating right now from Central America to other parts of the world, will be stepping on the sacred particles of their own land.”

—Taylor Dafoe

Ayana V. Jackson, Catch a Wave in “From the Deep: In the Wake of Drexciya with Ayana V. Jackson” at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C. Photo by Brad Simps, courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C.

Often the most memorable art experiences are the unplanned ones. For me this year, that was encountering “From the Deep: In the Wake of Drexciya with Ayana V. Jackson” during my first visit to the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art.

The Afrofuturist-infused exhibition is the first monographic show from photographer Ayana V. Jackson, created as part of a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship. The artist partnered with designers from both African and the Caribbean to create stunning costumes for the imagined denizens of the kingdom of Drexciya.

The underwater realm was first envisioned by Drexciya, a Detroit techno duo active in the 1990s. Its origins are in the slave ships that traversed the Middle Passage, and the pregnant African women who were thrown—or jumped—overboard during the harrowing journey. But Jackson’s show presents an alternate history in which those women’s babies were delivered by African water spirits, surviving to form their own magical, feminist society.

On view are mannequins clad in the otherworldly outfits of the Drexciyans and Jackson’s stunning photographs of women modeling each look. There are also video pieces, in which the artist, who was certified as a master diver for the project, is seen swimming more than 100 feet beneath the surface in Trinidad, Angola, and South Africa.

The show’s centerpiece, Catch a Wave, features hand-dyed indigo fabric and fishing nets formed into a dramatic gown, accessorized with oyster and mussel shells. The mannequin seems to float on a froth of sea foam, the dimly lit gallery suggesting submersion beneath rippling waves. The entire experience was utterly transportive, turning a tragic history into a beautiful and empowering vision that fuses art, fashion, and mythology.

—Sarah Cascone

Cecily Brown, Lobsters, Oysters, Cherries and Pearls (2020). Courtesy of the artist.

I went to go see Cecily Brown’s “Death and the Maid” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art twice. It isn’t uncommon for me to go see a museum show multiple times, but these two visits to this particular show at the Met made my experience with Brown’s paintings unforgettable. My first visit was alone, and I accidentally went in backwards, which was a blessing in disguise. I was immediately confronted by Lobsters, Oysters, Cherries and Pearls (2020), which at first gave me the animal-brained satisfaction of beholding lavish abundance, then delivered a one-two punch with the threatening appearance of a black cat lurking beneath the table—a reminder that abundance can easily be confused with excess.

The second-time I visited, my experience of the show was less about the narratives within each painting, but a testament to Brown’s technical skill. I brought a friend visiting from out of town who studied painting, but isn’t a working artist, to the show. The hidden moments and masterful brushstrokes he pointed out to me gave me a new appreciation for the show I could only get by seeing it with someone who truly loves painting. Because of that show, he left New York reinvigorated to pick up the practice again. Think painting is dead? Think again!

—Annie Armstrong

Portrait of 23-year-old medical student Aylar Haghi by Ania Tomaszewska-Nelson, one of the dozens of portraits featured in Say Their Names collective art project. Photo: Vivienne Chow.

On a sunny September afternoon while visiting Walpole Park in West London, my relaxing mood was interrupted by the sight of a tree outside Pitzhanger Manor and Gallery with dozens of postcards and roses dangling from its branches. These portraits were part of an art collective project called Say Their Names initiated by the London-based Iranian artist Anahita Rezvani-Rad to remember the hundreds of Iranian people reportedly killed since the protests following the death of the 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, who allegedly violated the rules of strict dress code for women.

But their names could not be spoken locally nor could their deaths be honored due to political pressure. I studied every single one of them. These portraits—paintings, drawings, or illustrations—coming in a vast range of artistic styles and conceived in different media, served as a form of memorial while creating an opportunity to explore the aesthetics, presentation, and meaning of portraiture today.

I struggled to hold back my tears as I re-imagined the struggle these people went through. You don’t need a fancy white cube and millions of dollars to stage a powerful, moving art exhibition. As the late Czech-French author Milan Kundera wrote, “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” Our memories are our greatest weapon, and art is here to help us to remember what must not be forgotten.”

—Vivienne Chow

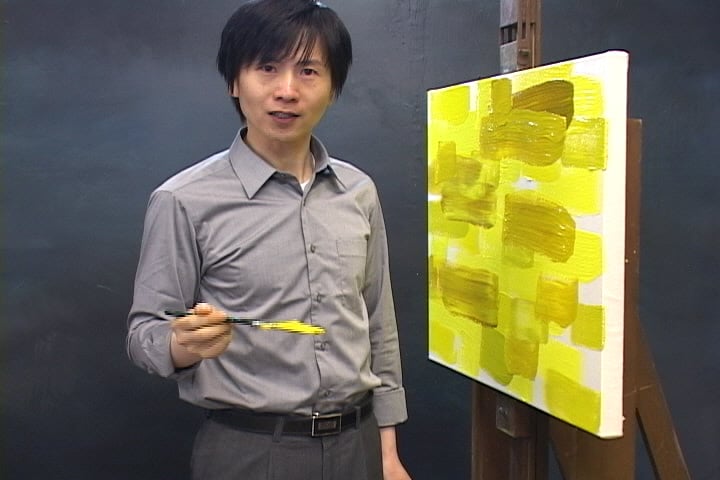

Painting “Yellow Scream”, 2012, single-channel video, color, sound, 31 min, 6 sec

The standout exhibition for me this year was “How to become a rock” at Seoul’s Leeu Museum of Art, a solo showcase by Kim Beom, one of Korea’s preeminent contemporary artists. The comprehensive survey featured over 70 pieces dating from the early 1990s to the mid 2010s, and included works previously unseen in Korea. Despite minimal explanatory texts on the walls, my post-visit research underscored the exhibition’s engaging nature.

The exhibition’s title, “How to become a rock,” derives from Kim’s 1997 artist book, “The Art of Transforming,” reflecting a key aspect of Kim’s artistic approach. His works are deeply rooted in animistic thought, embracing the belief that life and soul exist in all matter. For example, Kim’s early piece Pregnant Hammer interweaves various interpretations of the Korean word “nata,” meaning both to create (as with a hammer) and to give birth. A particularly memorable moment for visitors was viewing the tutorial video for Painting “Yellow Scream,” an instructional piece that guides viewers through the work’s creation, with the instructor audibly screaming. This act of vocal expression while painting symbolizes the artist’s intensive quest for elusive ideas and meanings, metaphorically representing the existential nuances of contemporary art as seen through Kim Beom’s eyes. Yet who in today’s art world could view this piece without a shared, knowing smile?

—Cathy Fan

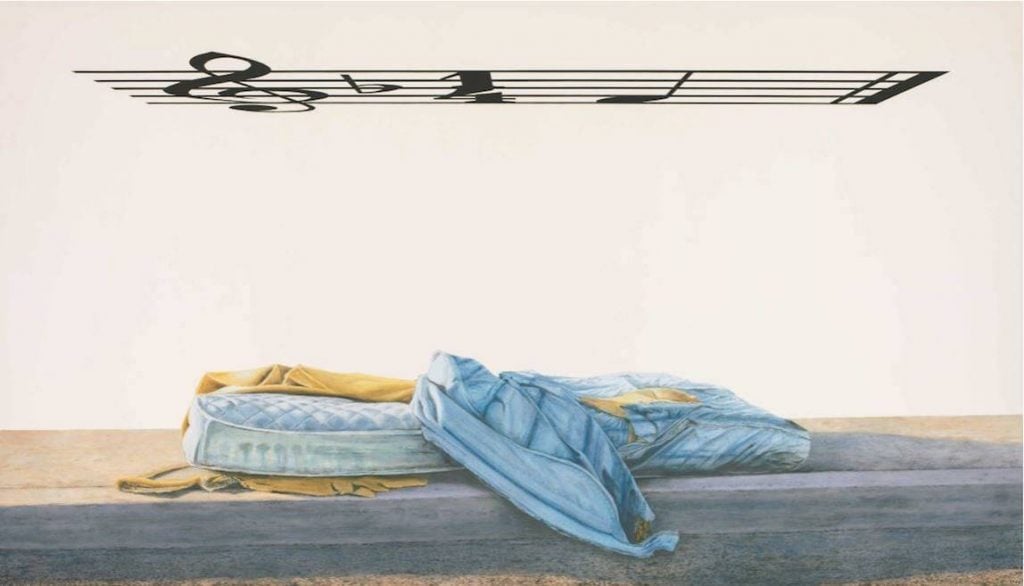

Edward Ruscha, Bliss Bucket (2014) Pinault Collection.

There are several reasons why I chose Ed Ruscha’s Bliss Bucket (2014) from the excellent “Now Then” retrospective on view at MoMA (through January 13, 2024).

First off it was so unexpected, and I’m saying this as an admittedly huge fan of a powerful “word” paintings like OOF. This painting, which was on loan from the Pinault Collection, might just be the most beautiful abandoned mattress anyone has ever encountered, rendered in intriguing shades of blue and gray.

Instead of calling up feelings of despair and decay, I was intrigued by how it felt equal parts beautiful and desolate and was also curious about the lighthearted, also horizontal format of the musical notes rendered above the supposedly depressing scene. I assumed I was wrong for finding it so peaceful and intriguing until I looked at the wall label, which offers an audio take and reads: “What makes this painting hopeful?” including a discussion of the opposite impacts of the words “Bliss” and “Bucket.”

—Eileen Kinsella

Fahrelnissa Zeid, My Hell (1951). Collection of Istanbul Modern.

This September I traveled to Istanbul for the first time to attend Contemporary Istanbul art fair, and during that trip, I had the good fortune to visit Istanbul Modern, a remarkable museum filled with the Modernist visions of many Turkish artists, which presents another, more global, perspective on the development of 20th-century art.

Far and away the museum’s showstopper was the scintillating, near-apocalyptic My Hell (1951), a kaleidoscopic geometric abstraction composed of shard-like shapes in blacks, whites, yellows, and reds by late Turkish artist Fahrelnissa Zeid. Born to a privileged Ottoman family of artists, Zeid lived a life of both charm and tragedy. She was afforded remarkable freedoms for a woman of her era—and was one of the first to attend art school in Istanbul. During her storied life, she spent time abroad living in Berlin and Paris, and she married several times. But the specter of violence hung over her always; her brother, whom she loved dearly was convicted of killing their father when she was a child. Her second marriage to Prince Zeid bin Hussein of Iraq made her royalty, but the couple barely avoided assassination after the Hashemite monarchy was overthrown in 1958 (the prince’s entire family was murdered). Seeing My Hell on the museum wall I stopped in my tracks—the painting evinces a burning world, perhaps the flames of damnation or war, through delicate, dancing forms that bring to mind wide-ranging Islamic and Byzantine influences, in a way I found powerful and unexpected.

—Katie White