People

3 Eye-Opening Facts About the Life and Work of the Beloved, Tormented, and Widely Misunderstood Painter Francis Bacon

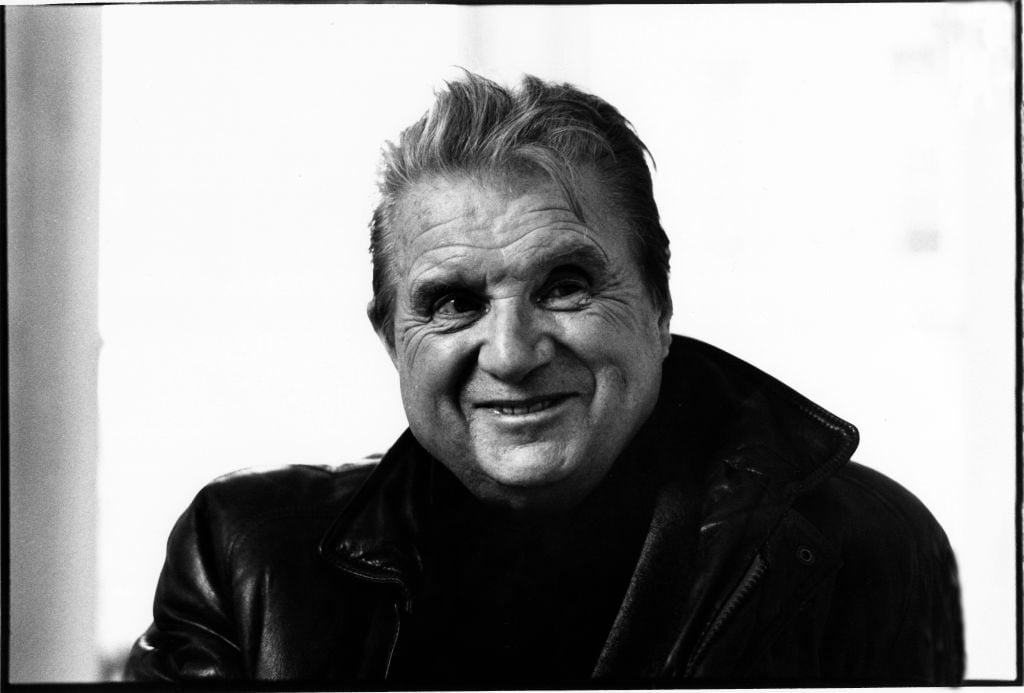

French writer Yves Peyré has published new information about his artist friend in a recent monograph.

French writer Yves Peyré has published new information about his artist friend in a recent monograph.

Eileen Kinsella

Fans of Francis Bacon, rejoice: a new publication by the French poet and author Yves Peyré, Francis Bacon Or the Measure of Excess, out now from ACC Art Books, offers a touching and intimate tribute to the Irish-born English painter who has become one of the most sought-after artists in history.

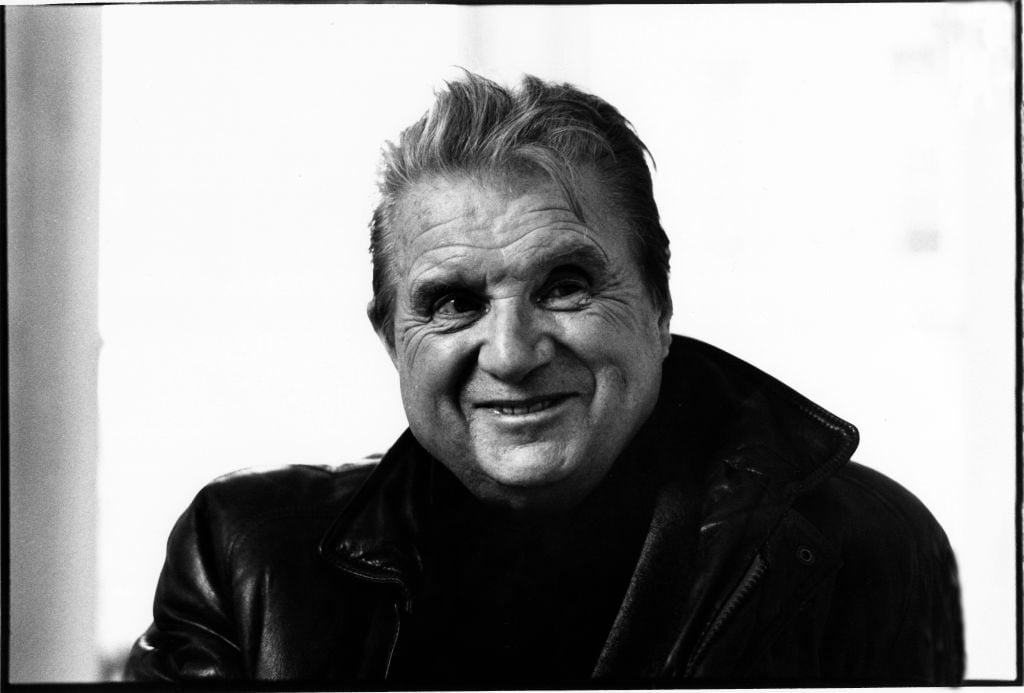

Bacon’s torqued figurative depictions of close friends, lovers, animals, and historical figures clearly struck a nerve with collectors early on, and the desire for his work has only increased over the decades. Many of the artist’s top prices have been realized in the past decade alone, including one of the top-selling works of 2020, Bacon’s Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus (1981), which sold for $84.5 million at Sotheby’s this past June.

Peyré was not only a major fan of the work; he was also a friend and ardent supporter of the artist. In his new monograph, packed with in-depth analysis and colorful images, he delves into the artist’s life and inner workings, exploring some of the incongruities between his public persona—his decadent lifestyle, outsize appetite for drinking, sex, and gambling—and his private life.

Notably, Peyré does not claim to know or to have directly witnessed all aspects of the artist’s life. As a straight man (and not a drinker), Peyré says his friendship with Bacon was somewhat unlikely. “I wrote my book out of loyalty to a work and to a destiny. I knew Bacon well, we were friends, I was also one of the people who he thought best felt his work, said things that delighted him,” he told Artnet News in an email. “I was aware that I could shed new light on his work, whether it was specific paintings or the general meaning of the work.”

Here are three revelations from the book about Bacon’s life and work.

Francis Bacon, Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus (1981). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Despite some decidedly negative reactions to his raw style, Bacon was revered in his day. In 1977, for an exhibition at Galerie Claude Bernard in Paris, the Rue des Beaux-Arts was closed to traffic to allow throngs of viewers to reach the gallery safely.

“The adulation he received was unprecedented in the world of art; there was a level of frenzy that you normally find only at certain sporting events, rock concerts, or major film screenings,” Peyré writes.

The author recalls walking down Boulevard Saint-Germain with the artist one day when they were interrupted by a man “who threw his arms around Bacon and thanked him. This unexpected but poignant scene was not unique, he told me; it happened to him every now and then.”

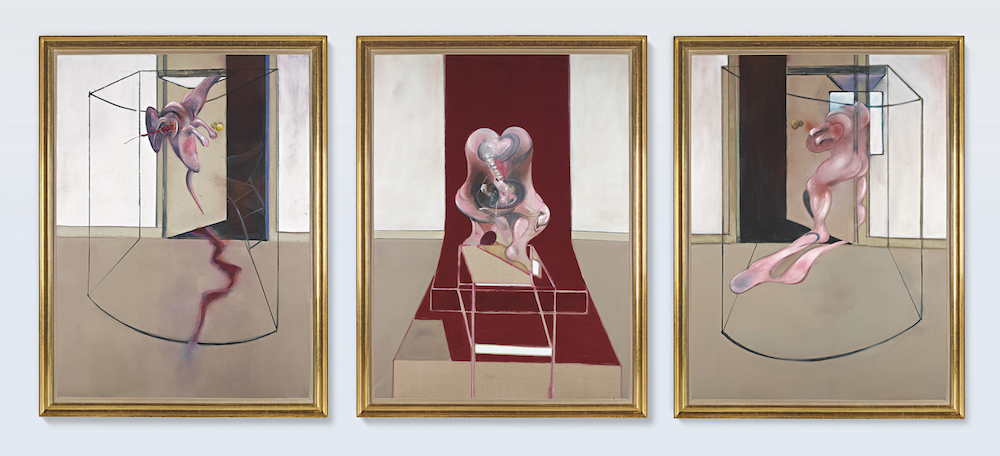

An image from Yves Peyré’s recently published book, Francis Bacon Or the Measure of Excess. Image courtesy ACC Art Books.

Bacon, who is famous for his hedonism‚ didn’t devote his life only to the pursuit of pleasure. Though Peyré concedes the artist was “dominated” by his lust for sex and alcohol, he still worked six hours each day, from morning into midday.

But the artist didn’t work in a linear way, Peyré writes. “Bacon’s work is so identifiable that it can give the impression that he had a virtually unique way of painting.” Yet the artist never repeated himself, even when dealing with the same subjects or using the same models.

He shifted angles, change his procedures, and varied between construction and violence in an attempt to realize “the most improbable tonalities,” Peyré writes. Certain subjects stopped appearing or returned after long absences. While heads and portraits remained throughout, landscapes returned after a lengthy lapse, and animals gradually disappeared. “Bacon is perpetually searching, subtly making use of forgetfulness or involuntary memory.”

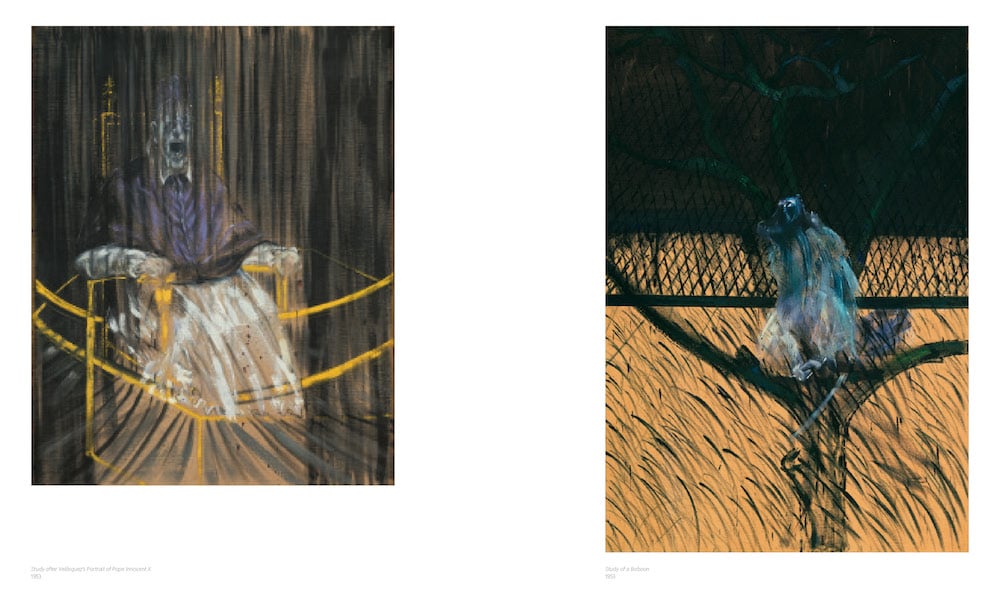

An image from Yves Peyré’s recently published book, Francis Bacon Or the Measure of Excess. Image courtesy ACC Art Books.

Though the artist is inextricably linked to the notoriously messy studio he maintained in London and the heydey of the Soho club scene, he had a deep love for other cities. He was “bowled over” by Paris, Peyré writes, which would always be for him the most beautiful city in the world and “certainly the most pleasant and most classy, which meant a lot in his eyes.”

He also loved Monte Carlo (where he would play at casinos) and was fascinated by South Africa, where his mother and sisters had moved, and traveled there several times. “The local vegetation fascinated Bacon, as did the indigenous fauna (especially the monkeys, those felicitous parodies of human beings),” Peyré writes.

Tangier drew him as well, largely because his close friend, Peter Lacy, lived there. “With the ambience of bars and hotels, the splendid parties, the cosmopolitanism of the residents, the colorful people, the parade of eccentrics, the permissiveness, the creative types (both artists and writers) who lived in the city, there was much to entice Bacon,” Peyré writes.