Archaeology & History

3,600-Year-Old Cheese Found in China Reveals Ancient Food Secrets

Researchers in China have discovered the world's oldest cheese in a Bronze Age burial site.

Researchers in China have discovered the world's oldest cheese in a Bronze Age burial site.

Samuel Reilly

Fermented dairy and mummies might not seem like the most obvious pairing, but archaeologists in China have just uncovered what they believe is the world’s oldest cheese—found in a 3,600-year-old tomb at the Xiaohe Cemetery in present-day Xinjiang. The discovery offers a surprisingly tasty piece of history that’s been buried for millennia.

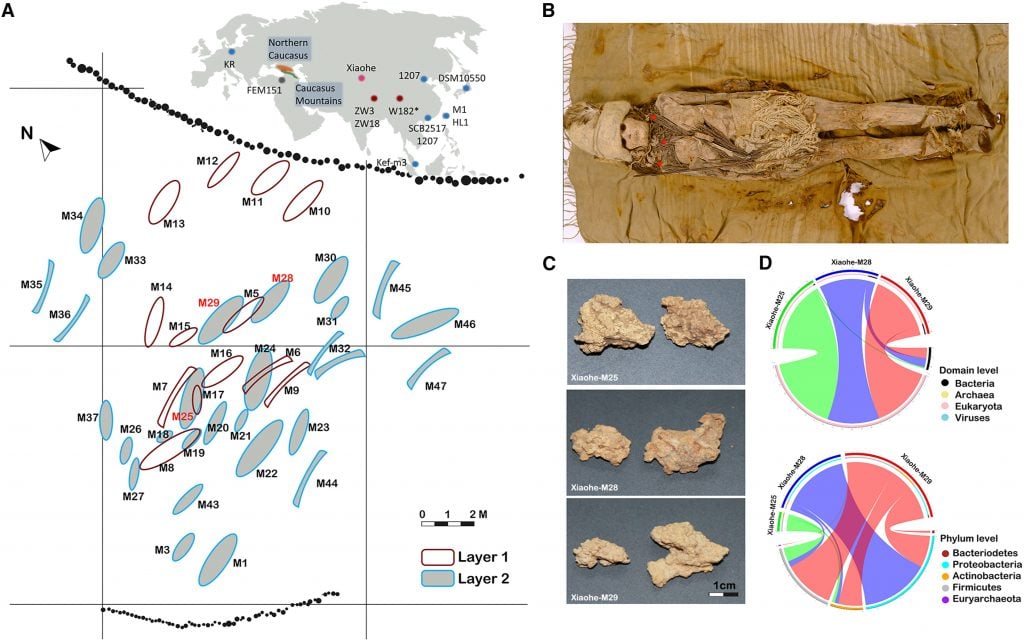

In 2003, researchers excavated a 3,600-year-old coffin at the burial site in northwestern China, which contained a young woman with an unknown substance laid out across her body. Recent DNA analysis by the team of researchers at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing has revealed that this substance was kefir cheese, with its inclusion alongside the mummy highlighting cheese’s cultural significance to the Xiaohe peoples.

A mummy from the Xiaohe cemetery, and dairy remains are scattered around the neck of the mummy.

Copyright: Wenying Li, Xinjiang Cultural Relics and Archaeology Institute.

Kefir cheese is made by fermenting milk with kefir grains, then draining the liquid to create cheese. The researchers found DNA traces of both goat and cow milk in the samples. In the report they have just published in Cell journal, the researchers hypothesize that, since the Xiaohe populations are known to be “genetically lactose intolerant,” the development of fermenting processes could have enabled them to add dairy to their diet, since the “process of cheese production reduces the lactose content significantly”—in addition to “extending the shelf life of raw milk.”

It turns out the shelf life doesn’t quite stretch to three-and-a-half millennia. “Regular cheese is soft. This is not. It has now become really dry, dense and hard dust,” Fu Qiaomei, paleogeneticist and co-author of the report, told NBC News. So unlike the honey found in ancient Egyptian tombs, this cheese is not for eating—but it does shed new light not only on the ways that Bronze Age populations interacted across the globe, but also how human cultural development has affected microbial evolution.

Courtesy Fu Qiaomei.

“It was previously suggested that kefir was spread from the Northern Caucasus to Europe and other regions,” the authors wrote in the report. But “we found an additional spreading route of kefir from Xinjiang to inland East Asia.” Their analysis of goat DNA suggests the spread of ancient populations from the Caucasian steppe, which “served as a corridor for human interactions.”

Further, analysis of bacterial specimens in the cheese has enabled the researchers to track the evolution of the Lactobacillus species that are crucial to fermentation and particularly of a subspecies, L. kefiranofaciens, with probiotic qualities. The researchers suggest not only that selective processes by humans during the fermentation process encouraged the development of these strains, with benefits for the immune system and the production of antibodies. They also observed horizontal gene transfer (HGT) events—a process where genes are exchanged between species, rather than inherited—with implications for our understanding of the problem of growing antibiotic resistance today.

The fermentation of milk can be traced back to around 6,000–4,000 BC in India, while it is known that Mediterranean populations were consuming cheese by around 5,000 BC. However, the new discovery is among very few examples of dairy remains preserved from more than 3,000 years ago, which has made detailed analysis of how and why prehistoric peoples created cheese very difficult. The title for the world’s oldest cheese residue was previously held by an example found in a tomb near Cairo in 2018—the first Ancient Egyptian cheese ever discovered—believed to be 3,200 years old.