Art World

Early Adopters of MoMA PS1 Look Back on Its 40-Year History

Alanna Heiss, Klaus Biesenbach, Laurie Anderson and others reflect.

Alanna Heiss, Klaus Biesenbach, Laurie Anderson and others reflect.

Daniela Rios

Founded in 1971 by Alanna Heiss in an old public school building in Queens, PS1 quickly became a bright star in the constellation of the alternative space movement. It opened its doors in 1976 with the show “Rooms,” for which it extended an invitation to 78 artists to decorate their space with art. Richard Serra created a work in the attic, Walter De Maria plastered one wall with pornographic imagery, and Vito Acconci created an installation in the boiler room of a sound piece with stools and a light bulb.

In the eighties exhibitions of artists such as Michelangelo Pistoletto’s “Mirror Painting“ (March 10–April 12, 1980), and Barbara Kruger’s “Photography” (December 7, 1980–January 25, 1981) cemented the institutions visionary approach to presenting art. And in the 90s shows featuring Marcia Hafif (January 14–March 11, 1990) and David Hammons (December 16, 1990–February 10, 1991) underscored the institution’s significance.

Over the years, MoMA PS1 (it was acquired by MoMA in 2000) has broadened its reach, combining PS1’s daring push for boundary-defying works of contemporary art and MoMA’s strength as a collecting institution.

In 2010 Klaus Biesenbach took over directorship of MoMA PS1 and continued Heiss’s legacy of of presenting cutting edge contemporary art by giving a platform to artists including Francis Alÿs (May 4–September 12, 2011) and Ryan Trecartin (June 19–September 3, 2011). The German curator also placed emphasis on broadening the scope of the museum by offering a Retrospective to the legendary techno band Kraftwerk and utilizing the former school as a concert venue.

In homage to the 40th anniversary of this storied New York institution, we reached out to several players who played key roles in its history and evolution, including Heiss and Biesenbach, as well as others who could speak to its iconoclastic roots. Happy Birthday MoMA PS1!

A general view of MoMA PS.1 on December 12, 2012 in New York City. Courtesy of Astrid Stawiarz/Getty Images.

Alanna Heiss, founder and director (1976–2008)

In 2001 we were preparing for a large Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller exhibition, complete with “burning houses,” audio walks around the building, and many other technically demanding works. The installation of 40-Part Motet was causing tremendous consternation in the Cardiff camp as they labored to correctly align the various sound channels representing the voices of the 40 singers. It was almost perfect.

Then the shock of the World Trade Center explosion hit NYC. The next day I called Janet and asked to open the show early. She and George quickly agreed. Everyone at P.S.1 worked shifts to keep the building open night and day for the next week. People started gathering in the piece, and these audiences grew and grew and grew. There was never any sound except for the Thomas Tallis hymn.

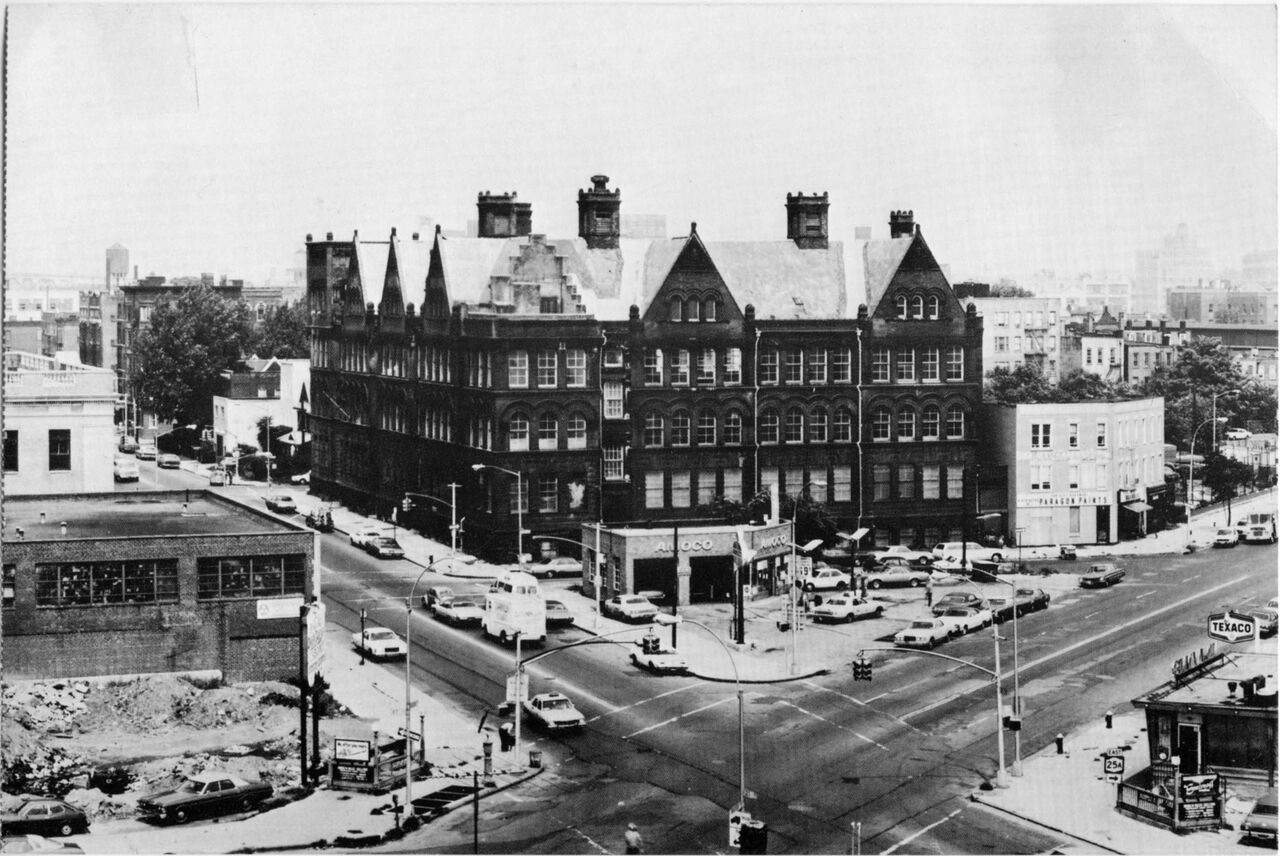

PS1 in 1979. Courtesy of MoMA PS1.

Richard Nonas, artist

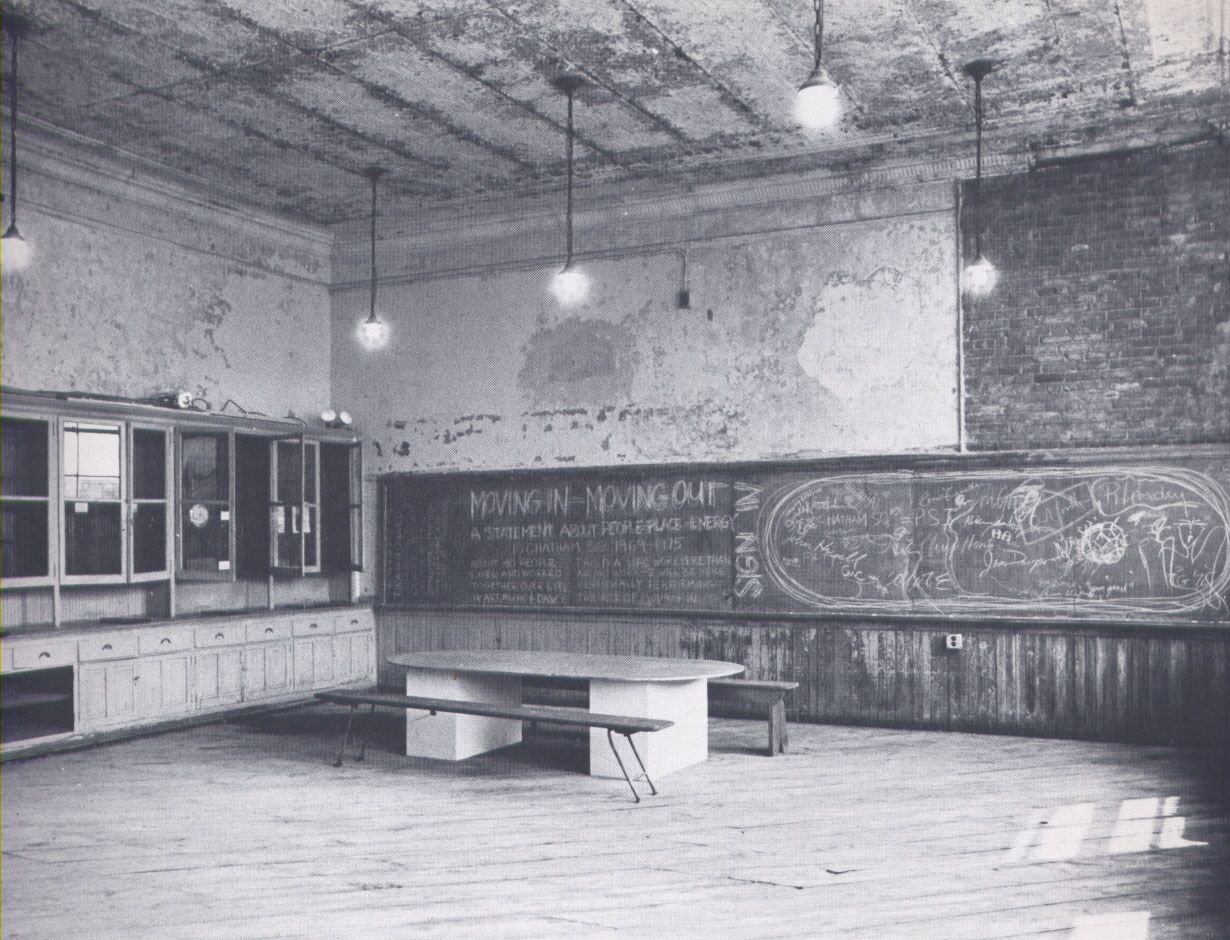

Each room was different because some had water up to your knees, some had water up to your ankles, some had seats in them still, some didn’t, some had desks. Each of them had a different history. Despite the fact that there was a large number of artists, everybody came in, and in a certain sense had a choice. You let people wander around, and at least until it became impossible, basically people chose the place they wanted to be. In the toilets, in the basement, in the attic, and that was kind of an extraordinary thing that could never happen again. There is an iconic quality, a historic quality, a mystical quality at this point, about that first P.S.1 show.

Fred Fisher, architect (1997 PS1 renovation)

Over pasta and wine at Manducotis, Alanna and her co-conspirators strategized countless ideas. Alanna is infinitely curious about people and art. Her love of both drove the realization of seemingly improbable art works, collaborations, and the realization of PS1 itself. She sees the essential connection between art , materiality, and architectural space. We met in connection with work on two installations by the California artists James Turrell and Eric Orr. We connected on the basis of staying close to artists and curators, creating a canvas, not a monument. She tested the evolving design of PS1 with her art world cohort. One memorable comment from an artist reflected the cherished place that PS1 was: “Don’t f### it up!”

Klaus Biesenbach, director, MoMA PS1, chief curator at large, MoMA

In 1994, Rebecca Horn’s Guggenheim exhibition came to National Gallery in Berlin. I think it was also a special birthday for her so everybody celebrated in a Greek restaurant in Berlin. It was very large family style dinner and in the later hours reminded me of a Greek wedding. Rebecca wanted somebody to jump onto the table and throw the plates against the wall, like in a wedding. Of course nobody would do this. Then she started cheering and the only two people jumping onto the table independently not knowing each other were Alanna and I. So we met at an artist’s celebration on a tabletop. From then on we became close collaborators and researched together in Thailand visiting dozens of studios, changing the upper floor of a Mexico City hotel into an artists’ club with DJs, co-curating the Shanghai Biennial, touring the night in Tokyo with Araki, and organizing Christoph Schlingensief’s infamous Statue of Liberty performance.

As a surprise to many, we for so many years collaborated as if we were inseparable, me being director of KW and she being director of MoMA PS1, I as her curator, she as my curator, friends for life, partners in crime: Bonnie and Clyde. When I finally left Berlin for good in 2004 and started full time at MoMA, I was finally a New Yorker. Alanna left PS1 in 2008, I started as its director and MoMA’s chief curator at large in 2010, so I didn’t immediately follow her but I owe her so much as a mentor! She taught me that it always has to be about the artist, the art, and that installation is about positioning objects in space and time, and that it has to be as serious as a question of life and death. And that it takes much more precision to install in a decrepit abandoned building than it does in a perfect white cube. Alanna founded MoMA PS1 to serve the artists and their dreams. I hope I can follow her in this legacy.

Brian O’Doherty, artist

Why were these spaces alternative? Because the galleries were very repressive in their way. And a redistribution of power occurred, because Alanna Heiss was involuntarily in competition with galleries. Artists were coming to her, and new talent was not flowing to the galleries but rather to alternative spaces. Galleries were not in control of artists’ lives, as they had been. At P.S.1, one could come in and attack the wall, pull up what one wanted from the floor—one could do anything. I remember one of my students, Alan Saret, had dug into the wall. This was amazing. Galleries would not have that. There was a tremendous sense of liberation in the Rooms show.

Tina Girouard “Revival” (November 15–December 9, 1978). Courtesy of MoMA PS1.

Robert Yasuda, artist

When I first got to P.S.1, I thought was a hare-brained idea. It was this massive building, and looking around at all of the debris, it was very exciting. We thought this was really, in a way, something we had not experienced before, in terms of scale. From our point of view, the important thing about P.S.1 is not only that it created a situation where we could do work that we could do nowhere else. But there was a buzz that started, that didn’t exist before. It was always with the idea of a non-gallery, non-commercial—this is a place for art at the moment. For us that was really important.

A general view during the Pier Paolo Pasolini MoMA Film Retrospective Opening at MoMA PS.1 on December 12, 2012 in New York City. Courtesy of Astrid Stawiarz/Getty Images.

Laurie Anderson, artist

This incarnation of P.S.1 is really fantastic. It looks much spiffier now, I have to say. And, I usually don’t like that at all. I just don’t like museums that much, but this is fantastic. It looks beautiful here! Very simple. And the building itself is gorgeous and funky, and the show “FORTY” is so well curated.

About 40 years ago was when I was kind of, like, spooking around—my memory of that is friendships. So, in everything I see here I see my friends—or my teacher. Here’s Sol LeWitt, he was my teacher for a long time. That’s why I’m an artist, really, is Sol. Also people shifting between sculpture and painting, and talking, and performance, and dance, and sound, is what P.S.1 was really doing 40 years ago! It’s really wonderful to see that represented. I think Alanna did an amazing job getting the spirit. But she knew all of us; she was part of the scene. So she’s a perfect person to say, “Yeah, what happened at Magoo’s that night,” you know? So, it is fun to see it. And, I’ve seen a bunch of my old friends here.

Kenny Schachter, dealer and curator

I organized a show entitled “Bingeing,” part of “7 Rooms/7 Shows” (November 8, 1992–January 10, 1993) along with fellow curators: Franklin Sirmans, Alain Clariet, Four Walls, Lois Nesbitt, Robert Nickas, and Calvin Reid and served on the International Studio Program selection committee at the same time. Alanna was omnipresent, unabashed, wildly dedicated and cursed worse than my kids (that’s a lot); she defined PS1 (and the reverse), the place was her spiritual and intellectual home (and more), evinced by the time I encountered her with her knickers around her ankles having a wee in the men’s room with the door swung wide-open. I jumped back; she could care less.

Dickie Landry, artist and musician

Opening night at PS1 in 1976, at the “Rooms” exhibition: Packed house! At the end of the opening everyone leaving via the staircase to the street. For some reason I am the first one to open the door to the outside. In front of me was about a dozen young kids with baseball bats and rubber hoses. They pointed to someone on the staircase and said, “That’s him,” and they barged in swinging. All hell broke out with a gang/artist fight. In the middle of it all I asked Gordon Matta-Clark, “Where is your truck?” “Around the the corner,” he replied. “Give me the keys,” I said. So I ran and got the pickup truck and came down the side walk, horn blaring, crowd scattered and my friends jumped in and we sped off.