Art World

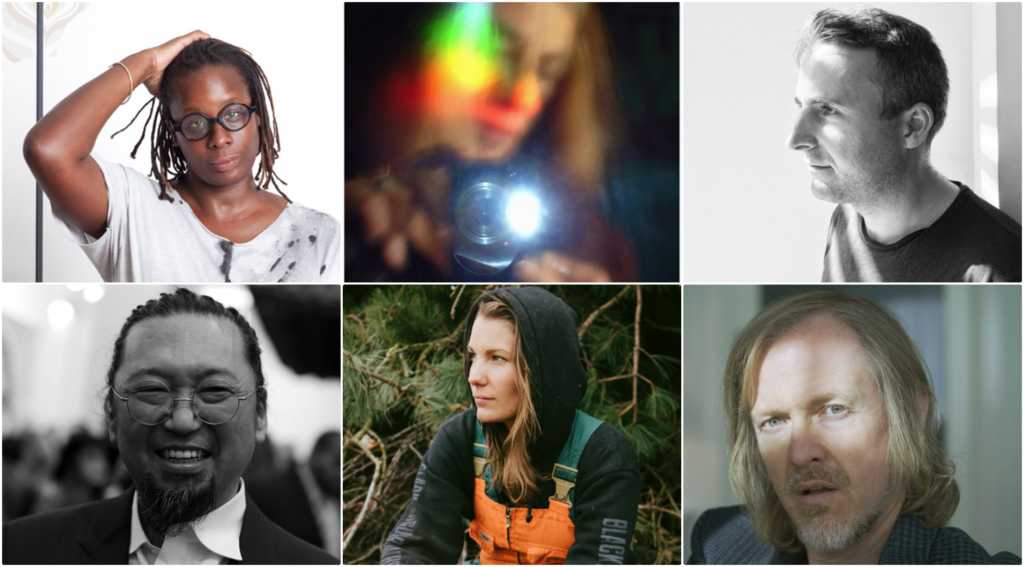

My Big Break: 7 Artists on Early Milestones That Changed the Course of Their Careers

Takashi Murakami, Dara Birnbaum, Mickalene Thomas, Boris Mikhailov, and more tell us about a moment in their career when everything changed.

Takashi Murakami, Dara Birnbaum, Mickalene Thomas, Boris Mikhailov, and more tell us about a moment in their career when everything changed.

Artnet News

Every artist has one: A chance meeting, an early discovery, or some other light-bulb moment that marked a new beginning and set the stage for the rest of their career. For Dara Birnbaum, it was the discovery of video art in a tiny gallery in Florence, Italy. For Mickalene Thomas, it was a high-profile commission in the window of the Museum of Modern Art.

We asked these artists and five others to tell us about a moment in their career when everything changed. Here are their stories.

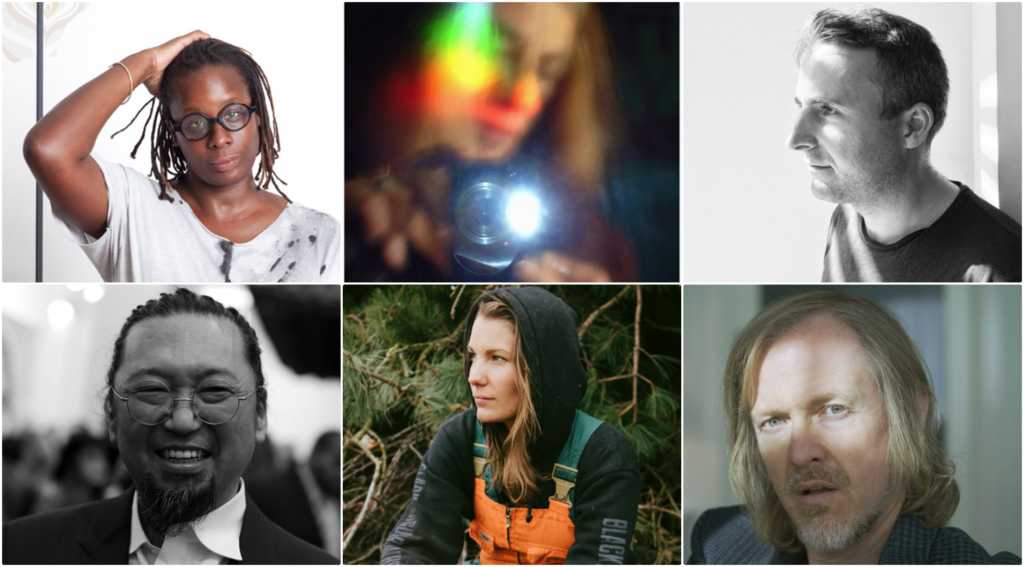

Boris Mikhailov poses next to his work at the Barbican Art Gallery, 2018. Photo by Ian Gavan/Getty Images for the Barbican. Right: A work from Mikhailov’s “Yesterday’s Sandwich” book. Courtesy of the artist.

While working as an engineer in the early ‘60s in Kharkiv, Ukraine, I volunteered, out of boredom, to make a film about the factory where I worked. In the process, I quickly got carried away with photography, which became my hobby.

At one point, I haphazardly threw some slides onto the bed, and I suddenly noticed how the frames laid down together. I saw how the frame in one film overlapped with the frame of the another and provided a complex and unusual picture. By moving and changing the combinations, I could get many more images from which I could simply select the most important. I managed to discover a method by which I was able to quickly obtain images that gave me some sort of metaphorical and unique picture of our life.

From the stacked slides (and there were about 300 of them), I made a slide show which, from the beginning of the ‘70s, I showed in photo-clubs along with the music of Pink Floyd. It became my first series and gave me confidence in my photography. And it was a turning point in my life—when I went from being an engineer to a photographer.

Left, Dara Birnbaum’s Self Portrait, courtesy of the artist. Right: Birnbaum’s Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978–9). Courtesy of the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix.

When, in 1973, I moved to Florence, Italy with my lover, I became homesick. I was there to go to the Accademia delle Belle Arti as he was going to attend graduate school in architecture. Neither really worked out for us. One evening, we thought we would be going to an “opera,” which in reality turned out to be a reading of the public works budget for the city that year. I ran out crying and headed back to a close-by storefront that I had seen and had intrigued me. In reality, it was an art gallery, Centro Diffusione Grafica, which was showing work by Vito Acconci and Dennis Oppenheim in its dual windows. I was unfamiliar with such conceptual artists. Then, in the back of that closed gallery, several people were watching what I assumed was television. They waved and invited me in. Surprisingly, that television turned out to be a video monitor, showing a work by Allan Kaprow. It was a complete surprise to me, something I never before encountered. As I became acquainted with the gallery’s owner, Maria Gloria Bicocchi, I was thus introduced to the beginnings of “video art.” I got to see work made there by artists such as Charlemagne Palestine, Richard Landry, and Joan Jonas. It shook me to my very core. It became what I wanted to pursue, thus changing my life and leading to the path I walk in the arts today.

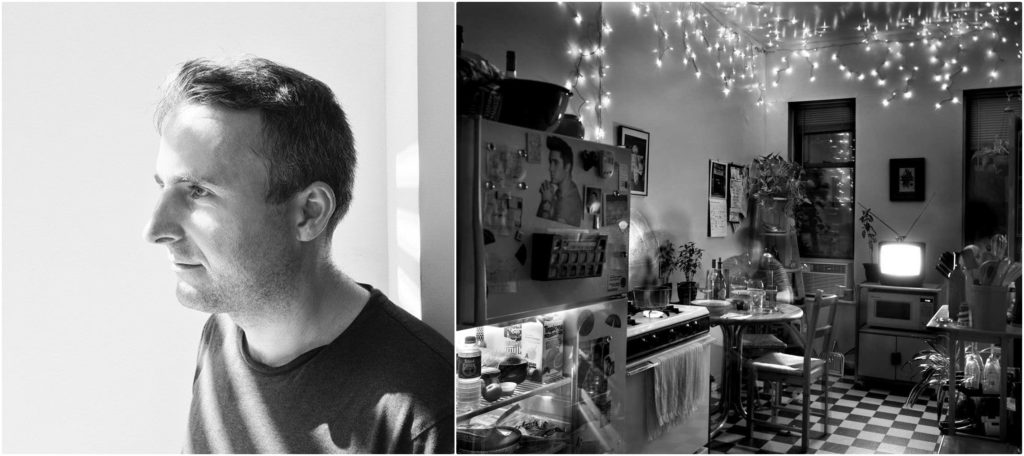

Portrait of Torbjørn Rødland; and Rødland’s Close Encounter #1 (1997). Images courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA.

I was a 27-year-old artist; he was a 64-year-old legend. The name Szeemann didn’t mean much to me, but I was told to take the meeting—this was a big deal. Harald Szeemann had seen my [photography series] “Close Encounters” exhibited in Oslo and wanted to meet. He was in the process of assembling a series of one-person exhibitions for Stockholm, the European Capital of Culture at the time.

It was 1998. I hadn’t learned humility yet and I was generally skeptical. He was full of enthusiasm and danced around me like a perky boy. I remember thinking, “Why is Harald Szeemann trying to impress me?” There are so many lessons in life, if only you’re awake to them. I was softly schooled in professional playfulness and introduced to a museum of obsessions. Is this what it’s like to collaborate with a curator? I’ve learned that it rarely is.

Four years later, he walked into a little gallery showing my Black project in Zurich and proudly declared that he had discovered me, which the gallerist humorously recounted to me. At the time, I thought, “Well, it wasn’t exactly like that…” But it probably was. In 1998, we put up a strange exhibition in a historical courtyard in central Stockholm, and just one year later, the same pictures were included in “1999 dAPERTtutto,” Harald Szeemann’s last Venice Biennale.

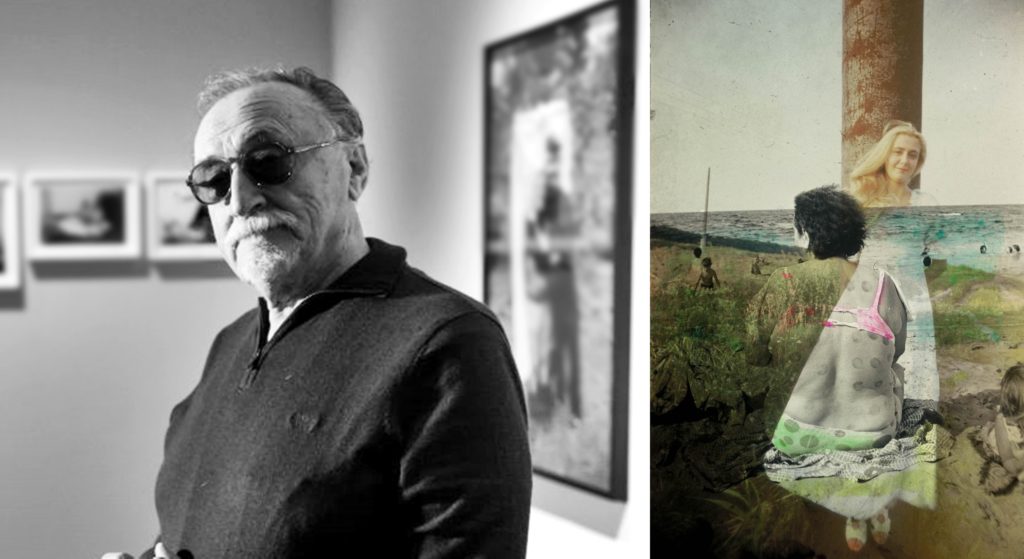

Mickalene Thomas. Photo Lyndsy Welgos, courtesy of Mickalene Thomas studio. R: Thomas’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires (2010). Photo: Brett Messenger courtesy of MoMA.

My first big break? When Klaus Biesenbach organized the commission of Le Déjeuner Sur L’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires for the front window of the Modern, the Museum of Modern Art’s restaurant. It was a site-specific project installed from 2010 to 2013 and it was shot in the MoMA sculpture garden; the same location where many phenomenal women artists had performed and exhibited before me. At that time, it was the largest painting I had made, at around 13 by 18 feet, and it was my most visible painting at that time due to all the press and visitor comments it received. This, however, predated the social media craze of Instagram and Facebook. It was a groundbreaking moment to have three beautiful, powerful, and sexy black women among the existing MoMA women.

Claudia Comte, portrait: Diana Pfammatter. Claudia Comte’s The Can (2018), courtesy of the artist.

A few years ago, curators at the Public Art Fund in New York invited me to be part of a group show. It was initially intended to be an exhibition paying tribute to the work of Barbara Hepworth, but in the end, the show became something else. It was on this occasion that I started to think about alternative materials to use in my work and began experimenting with marble.

This discovery inspired me to conduct entirely new research and to explore work that oscillates between what I typically do with my hands and the chainsaw, and a new technique that involves scanning and then milling objects using 3-D robotics. I realized that marble is not just an extremely precious or expensive material, but that, as with wood [the material for which Comte is best known], it’s another earthly resource. Like wood, it condenses an enormous amount of time and embodies a climate that has changed over the millennia. It opens up its own cosmos and has led me now to work in 4-D animations.

Takashi Murakami. Portrait of the artist, 2018. ©2018 Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Before I had a studio and started painting Manga-like characters and concrete objects, there was a time when I was working with middle-aged fabricators in a local workshop setting, making huge installation pieces or silkscreens. Basically, I would be hiring them out of the phone book. They would always ask, “So what do you do, young guy?” And I would have to say, “Well, I’m an artist.” And then I’d try to explain: “I want to utilize your technique in order to present my work in a certain way.” And they would ask, “Why?”

I worried that for them, the job might feel like an incomplete way of using their technique. And then, faced with that kind of question, I realized, “Well, I can’t tell them a lie. But it also wouldn’t make sense to just tell them the full truth.” So I had to come up with a middle-ground story that would motivate them to go on with the production.

Before, when I was just painting all by myself, I thought that kind of thing was really untruthful. There was no need to come up with a story or convince anyone else to do anything. But then through involving other people in my process, I realized that you can’t always just say, “It’s either A or B.” I have to come up with A-dash, and B-dash, or maybe C. When I suddenly understood that that’s what it means to work with other people, I feel like that really changed me.

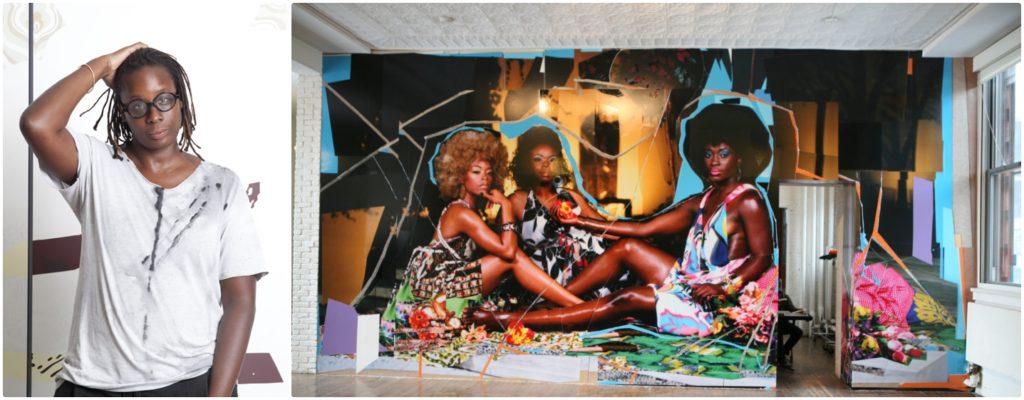

Matthew Pillsbury, portrait courtesy of the artist. Right: Pillsbury’s Anamika Bhatnagar & Dennis Willette, BBC World News/Access Hollywood. Thursday, October 2, 2003, 7–8pm (2003). Courtesy of the artist.

In early August of 2003, I met with [the New York dealer] Bonni Benrubi. I had graduated from Yale in 1995 and had not had any success in getting my work shown. At the time, I was in graduate school at SVA and had started photographing my friends watching their favorite TV shows, taking a single exposure for the duration of the program they were watching. At the end of the year, I felt like I had a solid group of images that my teachers and classmates were responding to, but I wanted to receive feedback from people in the gallery world before beginning my thesis year.

Bonni was the first person I contacted and she agreed to meet with me. She had reviewed my work in the past and had always been kind, but was never interested in showing it. This visit was different: It ended with her asking me to bring a box of prints to the gallery the very next week. She was unsure if people would buy them because of their intimate nature but she wanted to show them to her “good luck charms”—a small group of friends whose opinion she trusted.

The weeks that followed were a whirlwind whereby each of the “good luck charms” not only liked my work but acquired prints. Sandra Phillips [the longtime photography curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art] bought two prints for the collection of SFMoMA.

When I got that call, I ran around my apartment, my feet never touching the ground. By December, Bonni had sold over 85 prints and my work was in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, among other institutions.

The initial success was due in part to Bonni’s decision to price my work very low (the prints started at $700). She wanted to put my work out into the world and argued that there would be plenty of time to raise prices later.